Bill Hagan felt his head push beyond the pillow and into the headboard. As he came to consciousness, he realised it was not a headboard but the reinforced plastic bulkhead of a plane. At the moment he realised he was on a plane, he remembered that he was the captain of it. His feet were pitched up at 30 degrees in the flight crew’s bunk, at twice the angle of take-off. His first thought was that his two co-pilots had pulled up the aircraft’s nose because of oncoming traffic. When the plane banked sharply to the right, he wondered whether they’d swerved to avoid space debris. For a few seconds the aircraft seemed to level, then rose again, before turning sharply to the left and beginning to fall on its side.

Hagan had not been able to find his pyjamas before his rest break, and he entered the cockpit through the bunk’s adjoining door in his underpants, as British Airways Flight 2069 fell nose down at the rate of 30,000 feet per minute. “Something has been bothering me for a quarter of a century,” he texts me on a Sunday night 25 years later. “How did I manage to get into the cockpit with the aerobatics going on? I now realise I entered at the precise time the G-forces were changing from positive to negative, making me light on my feet.”

His co-pilot Phil Watson was strapped into the right-hand seat – the left should have been filled by his colleague Richard Webb but was empty – and another man was slumped over Watson’s lap, hooked on to the control column. Hagan pulled on the man’s shoulders, but three times he lost his grip. As the plane descended, he had a profound feeling of shame. He’d worked out that the Nairobi-bound flight would be somewhere over the Sahara Desert and this thought bothered him most. “Because it would be worse than Lockerbie. Because there is nothing there, just sand. The aircraft would be broken up, and bodies all over the place.”

We meet on Guy Fawkes Day at Edinburgh Airport – Bill has driven from his home near Glasgow. He is robust at 78, carrying a rucksack, and he has not brought his wife, a former air stewardess, though he had warned me she might come: “To keep an eye on me. She doesn’t approve of my views on the flight!” He has an easy laugh, a quick Northern Irish accent and an energy committed to getting things right. Our interview will largely take the form of a presentation, the same one he delivers at after-dinner talks for aviation enthusiasts around the country. I’ll ask a question, and he will say, turning back to his laptop, “It will all become clear.” He brings out reams of papers obtained in 2013, via the Freedom of Information Act.

Treat yourself or a friend this Christmas to a New Statesman subscription for just £2

It is most useful, he says, to compare Flight 2069 to a mega roller-coaster, and he had woken up in the ascent. Then, as the plane headed down, the velocity increased. He shows me an image, made by a friend, of an aircraft at a “bank angle” of 94 degrees, its wings perpendicular to the ground, a great cross on a dark blue sky like the sites on an air rifle.

On the pinkie finger of his right hand is a round white scar where the man who took the controls, a 27-year-old Kenyan student named Paul Mukonyi, tore off a chunk with his teeth. This was not unprovoked: Hagan had just pushed his middle finger as deep inside Mukonyi’s right eye as he could. “I was trying to damage his brain.”

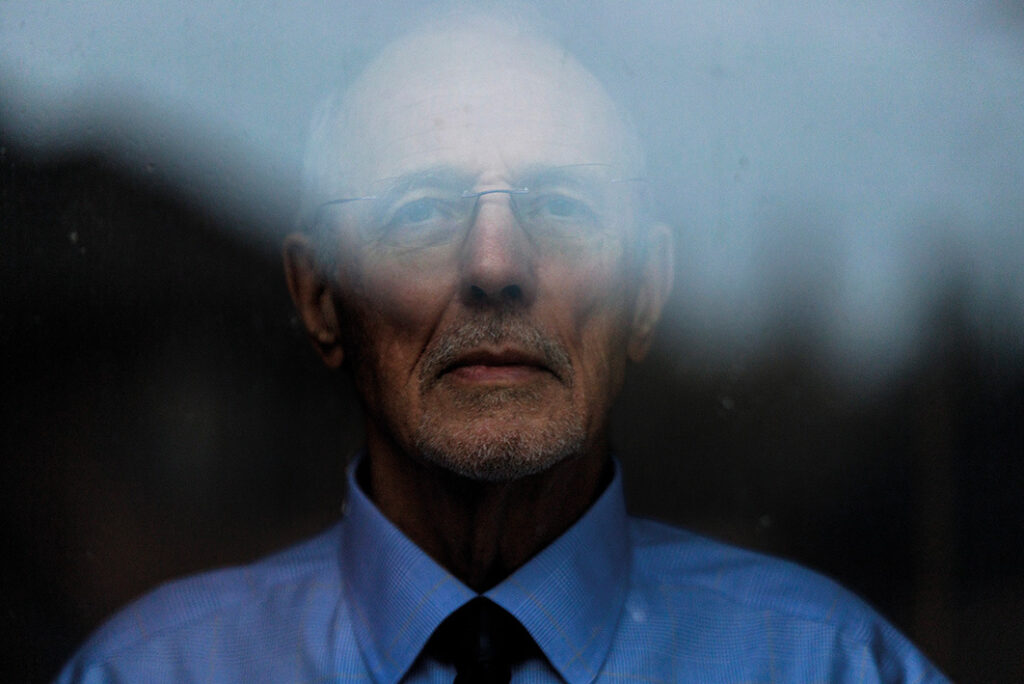

Bill Hagan, photographed by Robert Ormerod for the New Statesman

Bill Hagan, photographed by Robert Ormerod for the New Statesman

There isn’t usually snow at Christmas in the UK but in December 2000 there was a great dump of it, the most in nearly a decade. Much of it fell on 27 December, the night before BA 2069 left Gatwick for Nairobi at around 10pm. Luton airport had 20cm on the ground and was closed, as were the airports at Glasgow, Stansted and Liverpool. For a BA captain like Hagan, it was either work at Christmas or at New Year: his wife, eight-year-old son and 13-year-old daughter would travel to Nairobi with him, staying at the Hotel Intercontinental. While in Africa, he’d make shorter flights to the Seychelles and Dar es Salaam, and officer Richard Webb would play golf; he always kept his clubs in the flight bunk.

The ten-year-old Boeing 747, tail number G-BNLM, was being de-iced when Hagan arrived at Gatwick, and the cabin crew had already boarded. One of them told him that a Kenyan man had been brought onboard who said he was being followed; he had travelled up from Lyon, and asked for a police escort through the airport. The escort had told him the plane was the safest place for him. The steward asked Hagan whether he was happy to accept the man, and he replied, “‘Are you happy?’ Because they would have to deal with him on the flight.” The man was placed in seat 32H near the back of the plane, close to the cabin crew. Then Hagan went through the aircraft as he always did: “Pilots were encouraged by BA to leave the cockpit, to go down into first class and talk up the airline.” There was no turbulence forecast, and the night was clear – you could see the Eiffel Tower from 23,000 feet.

“I remember thinking, ‘Is it going to hurt, or is it going to go black?’… I wasn’t ready to die, but in that moment, I was embracing it” – Jemima Khan

In those days Boeing 747s, with their Rolls-Royce engines, were the queens of the sky. Three times the weight of the 737 and even the relatively new Airbus A319, their huge momentum would push through turbulence almost undisturbed. The aircraft has a small upper deck of around 30 seats from which the cockpit is accessed, usually reserved for business class. In this section, in row four, were the rock star Bryan Ferry, his then wife, Lucy, and two of their sons: they were heading to Zanzibar for a holiday. Downstairs, in first class, were Lady Annabel Goldsmith, her daughter Jemima Khan, then aged 26, Jemima’s two young sons, her brother Ben, cousin Cosima and her two children – eight members of one of the wealthiest families in England.

Since many commercial jet crashes have no survivors, there is a degree of mystery as to human behaviour on board an airliner that’s in serious trouble. Those who have escaped such situations have sometimes reported surprising docility and passivity at a time one might expect hysteria: flight attendants have described having to unbuckle people’s seatbelts on a successful crash landing to rouse them into leaving the plane. The majority of those on Flight 2069 were asleep when Paul Mukonyi folded up his belongings at around 4am UK time, headed up the stairs into the toilet at the front of the plane, then came out and quietly let himself into the cockpit.

Bryan Ferry speaks to me from his recording studio in west London: he does not remember much time elapsing between waking and knowing what was going on – he was close enough to the cockpit for the news to have travelled. The relative quiet among passengers was a contrast to the sound the plane was making as it fell through the sky, the metal straining as the pilot pulled on the controls to try to bring up the nose. “It was really the grinding and shuddering of the plane that is the strongest memory. Sounds I had never heard before or since – we were falling through the air and then going up again.” He found himself telling his teenage son not to swear.

Jemima Khan tells me that downstairs, where first class and economy were seated, no one knew what was happening. As the plane fell, a trolley smashed into an air stewardess, breaking her leg. Another member of the cabin crew crawled down the aisle on all fours. Khan had her four-year-old son on her lap. “I was very caught up in trying to make my son’s last moments alive as unpanicked as possible. Everyone was screaming around him, and I kept telling him to look me in the face.” Khan remembers a sound: “The sound, I suppose, of collective male groaning, a noise that came from deep within.” She attempted to hold her mother’s fingers through the gap between the seats. And she “bartered with God”, as she puts it – others started praying too: “The Lord Is My Shepherd”, and Arabic prayers behind her.

“I don’t think there was anyone on the plane who thought anything other than ‘we are going to die’. I remember clearly thinking that I wanted it to happen very quickly. I thought, ‘Is it going to hurt, or is it going to go black?’ I was very frightened of that resignation afterwards – frightened that I was willing my death on. When I was a child, I used to keep pet rabbits and sometimes my dogs would get them – they’d run and run, and then there’d be a moment when they would go very still. It was like that. I wasn’t ready to die, but in that moment, I was embracing it.”

The two Americans in the second row of business class were on the larger side. Clarke Bynum, then 39, had been a professional basketball player, one of the top passing forwards in the history of the Clemson Tigers. He’d swapped seats with his friend Gifford Shaw for the extra leg room and was sitting in the aisle. Shaw, 45, was from the wood truss manufacturing business – both were from prominent families in the town of Sumter, South Carolina, and had always known each other. They attended the Westminster Presbyterian Church, and they were embarking on a ten-day mission trip to teach the Bible in Uganda: Clark’s first, though Shaw had been before.

Gifford Shaw was a competitive man. Missions to Africa were the big time – he looked down on friends who stayed local and went to the poorest parts of Appalachia. “They didn’t go to places where there was danger,” he says down the line in his luxurious Southern accent. “I mean, come on, people, that’s not suffering for Jesus. That’s how bad I was.”

He and Bynum should not have been on BA 2069 at all. Their plane from the States was rerouted to Heathrow because of the snow and they travelled to Gatwick by bus, missing their connecting flight. They were reticketed by BA to travel to Uganda via Nairobi.

Shaw was asleep when Mukonyi entered the cockpit. He tells me that as the plane started to fall nose down, “I thought: ‘OK, this is what You prepared me for, I’m ready to die.’ For the first time, there was no fight contending in my life. It is peaceful to think there’s nothing you can do, unless God shows up.”

Bynum did not feel the same, and headed towards the cockpit. A second man followed – “Anglo Saxon,” says Shaw, with blonde hair and a blue shirt. At that point, Shaw stopped feeling peaceful and decided to follow too.

He breaks off. “It’d be interesting if you could help on this bit of the story. Do you know how many passengers went into that cockpit? Because I know I followed someone in, and no one has ever been able to find him.”

The incident on Flight 2069 lasted two minutes and 38 seconds. When Hagan remembered that he was above the Sahara Desert, he also remembered that his wife and children were onboard. The thought of his son recalled a conversation they’d had over Christmas, when Aidan had asked his father what he would do if he was swimming and came face to face with a shark. Hagan had told him he’d jam his fingers into its eyes.

When Paul Mukonyi was temporarily blinded, he and Hagan fell backwards and Phil Watson, at the controls, was able to pull the plane out of its dive. Shaw and Bynum – along with several others including Richard Webb, who had made it up the aisle on his knees – dragged Mukonyi out of the cockpit. From row four, Bryan Ferry watched “what appeared to be a James Bond scene, the white shirt and epaulettes – it looked like they were play acting. You didn’t expect to see a battle on a plane. Not in those days. Maybe now you do.”

As he was tying Mukonyi up, Shaw recalls, he heard him say: “I’ll show you the others with me.” He was placed at the back of the aircraft where he remained quiet for the remaining two hours to Nairobi. Upon landing he was taken to hospital, where he was judged to be suffering from paranoid schizophrenia. Mukonyi was released four weeks later with no criminal charges and returned to Lyon to pursue his studies in tourism. There was no permanent damage to his eye, and the hospital attempted to invoice British Airways for his treatment.

A photo taken aboard Flight 2069, with Bryan Ferry in the foreground and Paul Mukonyi on the floor outside the cockpit, subdued by passengers and crew. Reuters

A photo taken aboard Flight 2069, with Bryan Ferry in the foreground and Paul Mukonyi on the floor outside the cockpit, subdued by passengers and crew. Reuters

As Christmas 2000 slipped into 2001, Bill Hagan, back in Glasgow, wrote at his computer for eight hours a day. He shows me some of the notes he made. “Hit head, slippery – first pull – HORROR then vertically, then horizontally, slipping away…” The second part of his presentation is called “The Cover-Up”, though he asks me to avoid the word.

Hagan has identified seven separate “loss of control” events in the short period of time in which Flight 2069 was in trouble, which he says are supported by the flight data recording. A “loss of control” event is anything that causes the plane to deviate from its original flight path: if there is just one, it counts as a significant incident and has to be investigated. “This is probably the worst non-fatal event in aviation history,” Hagan says. Yet there is no publicly available report on it in the vast database of the Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB), an independent body within the UK government tasked with investigating serious incidents on civil aircraft, from losses in cabin pressure to damage to landing gear.

Two days after the flight, on 30 December 2000, the UK Department of Transport’s Threats Office classified the event as “air rage” – a significant move, Hagan says, because it indicated a brief altercation, rather than someone trying to take control of the plane. The report states: “The intentions of the passenger were not apparent although media reports of interviews with the aircraft captain and some passengers state that the man had made threats of committing suicide by crashing the aircraft. BA and Kenyan police authorities have, however, ruled out hijack as a motive. Unless directed otherwise the incident will be recorded under the miscellaneous category.”

Hagan shows me an epic paper trail he has amassed over the years: a letter from the UK’s deputy high commissioner in Kenya asking for an urgent review of cockpit security; another from the AAIB explaining that they were unable to participate in an investigation because the Kenyans were treating the event as a criminal act – an apparent contradiction to the Threats Office statement. And complaints from passengers’ solicitors to the Civil Aviation Authority, saying that the absence of an independent investigation into an “apparently premeditated suicide attempt” is not in the best interests of the flying public.

“My story is so huge. It has so many little fingers to it,” Hagan tells me. “I was kept in the dark, by and large, for a very long time.”

Phil Watson is a neat, fit man who retired from BA two years ago. He picks me up in a blue Mercedes from Chester Station and drives in confident sweeps through the town in the rain. He has not spoken about Flight 2069 since 2001. “I boxed it, as I did with all my close shaves. I didn’t have counselling, because I didn’t feel that I needed any. I could put it in drawer. It hasn’t overwhelmed me. I haven’t given talks about it. It was an event, move on.”

A few years back, a fellow pilot and golfing buddy of Watson’s was flying a jumbo jet from Johannesburg when mechanical failure caused the plane to get stuck in a configuration at which it was unable to climb. With 400 passengers onboard including his wife, who ran into the cockpit, he was forced to fly four or five miles never reaching above 200 feet in the sky. The incident became stuck in his short-term memory, playing on a continuous loop. British Airways provided him with specialist help from a therapist who used various techniques to shift the event to his long-term memory. “The essence of what I’m trying to say,” says Watson, “is that sometimes people sometimes need help – I’m not saying that Bill does, or anyone else does, but their experience is very different from mine.”

On the walls of Phil’s study are photographs of his father, Royston Watson, a squadron leader in the Korean War who completed over 100 missions and at one point held the height record for successfully ejecting from a serviceable aeroplane with a parachute: 42,500 feet, though he never talked about it.

Royston lived to see his son flying with the RAF 56 Squadron at Wattisham at the time of the First Gulf War; Phil then became a weapons instructor in Wales. He flew Phantoms – a supersonic fighter jet with a nose as sharp as a fountain pen. When he dreams about flying, he is always in one of those planes.

A loop or a barrel roll play havoc with the inner ear, and in every aircraft, military or civilian, the pilot uses an “artificial horizon”, containing a gyroscope, to tell whether the wings and nose are level if G-force is interfering with their senses. One night in 1988, Watson was doing a practice intercept on an RAF Tornado, travelling at the speed of sound. He mishandled the plane and ended up nose down in complete darkness at 700 miles per hour. In his altered state, he believed himself to be back in the crew room, rather than in an aeroplane, but when he heard his navigator saying repeatedly, “Phil, talk to me,” he was able to pull back and level the aircraft at 4,500 feet. When he returned to the mess in shock, his fellow officers told him of harder manoeuvres they had executed. “There’s this phrase in the military: if you’re looking for sympathy, you’ll find it in the dictionary between shit and syphilis!”

He shows me his father’s logbook from the 1950s with night missions written in red: “Hit two times, one 1,000lb bomb, position destroyed.” Then he shows me his own: “December 24: CA-LHR. December 29: Man tried and failed to kill all pass and crew over El-Obeid, Sudan. January 11: LGW-MIA.”

Watson, 38 at the time, was the non-handling pilot on Flight 2069, meaning he didn’t execute take-off and landing; at dawn on 29 December he briefly found himself flying the plane on his own. Richard Webb had stepped out to “stretch his legs”, and Hagan was taking his rest break. He was wearing his lap belt when Mukonyi threw himself at the controls.

Watson’s brain works a bit like a computer. This nosedive was different to the one he’d done in the military. For a start, it was nearly dawn, and he could see the real horizon coming up at 90 degrees outside the window. He noticed other things happening to him, like the fact that everything went into slow motion, as it did when he’d been knocked off his bike by a car at 14. As he had headphones on – and was “coned”, in his parlance – he could hear nothing: “Your senses are just the visual.” He tried to peel Mukonyi’s fingers back off the controls; then he punched him in the head three times and bit into his forearm. He shows me the knuckle on his right hand which is permanently enlarged.

When Hagan pushed Mukonyi’s eye in, and the pair of them fell back, they tore off Watson’s epaulettes and shirt buttons. By the time Watson was free to control the plane, it had dropped 10,000 feet and was in a stall.

A stall in an aircraft is nothing to do with the engine, but means that there isn’t enough airflow over the wings to lift the plane. It will begin to fall, and once the speed of descent reaches a certain point it is unrecoverable. Watson initiated what is called a stall recovery, pushing the plane forward, nose down, in order to increase the airflow over the wings: when this failed a first time, he did it again, pushing harder and faster towards the ground. It was a manoeuvre rarely practised in BA’s flight simulators, and not one you’d expect to execute in a huge airliner with 400 passengers. “I thought: ‘I’m going to get bollocked by the management when they see the trace.’” He downplays the stall recovery, as he downplays most things, but he adds that levelling the plane “ensured that we weren’t going to die in less than a minute”.

At his feet are medals he received for his actions, including the coveted Polaris Award, also given to Hagan and Webb. Watson has never heard Hagan’s theory of space debris or oncoming traffic, or the explanation of how he got into the cockpit assisted by G-force. I tell him that Hagan pictured Lockerbie and he stares back at me blankly. “My brain was saying, ‘Let’s get him out of here and let’s get back to what we were doing.’ Never, even to this day, has a thought like that even entered my mind. Maybe I’ve got a small brain? It’s possessed Bill. I don’t mean that in a nasty way. Wife and son and daughter onboard… from minute one, it’s affected him that way, he’s gone down a different track from me. I don’t envy that.”

Hagan and Watson, who had never worked together before, have differing accounts of when Hagan arrived in the cockpit to help. Watson says he’d already got the plane level: Hagan says that pulling on Mukonyi’s shoulders helped bring the plane out of its dive. They no longer speak. “But we haven’t fallen out,” says Hagan. Watson shows me a copy of an aviation magazine with Hagan on the front and the back, shaking the hands of high-up personnel; Watson did not get as much publicity. Hagan wrote a book, but Watson wouldn’t corroborate the facts, so it remains unpublished. According to Watson, the book included lines like “God lifted the plane out of the sky” – “and I thought, no thanks!” he says.

Yet both make clear, repeatedly, that neither could have saved the plane without the other – Watson talks of Hagan’s “genius move” with Mukonyi’s eye. Both were treated for their injuries in Nairobi – with Mukonyi in the next ward, tied to a stretcher – and they flew home together the following night.

In early 2001, First Officer Phil Watson campaigned for increased security, proposing a keypad entry system for the cockpit door

Underneath Watson’s medals is his own folder of paperwork on Flight 2069, some of it the same as Hagan’s, including its air rage classification by the Threats Office. “I guess this would be possibly an attempt to downplay it,” Watson says casually. “Not an accident. Not even an incident. I would have said incident…”

At the turn of the millennium, commercial airlines were in a rather precarious state. Pan Am had been finished off by Lockerbie; the low-cost American airline ValuJet went under when one of its DC-9s crashed into the Florida Everglades killing everyone onboard. “This is why the continuity manager is copied on the incident report from British Airways,” Hagan had told me in Edinburgh, thumbing a piece of paper. “They were thinking: has this incident got implications for the future of the airline?”

Watson dismisses Hagan’s detective work while suggesting that much of what he says sounds entirely plausible. “It’s in BA’s corporate interest to downplay it all as much as possible, because the outcome was successful. Anyone in their right mind would do that, because it’s going to affect our numbers and our reputation.”

He tells me he and Hagan were interviewed at Gatwick Airport three and a half months after the event. “We said, ‘Why does someone want to speak to us now?’ and the guy said, ‘Well, it’s been hush-hushed by the Home Office.’ So this adds a little fire to what I’m guessing Bill Hagan thinks about it.”

Watson spoke to the pilot of the Airbus that brought Mukonyi to London from Lyon: “You could see how there’d be an angle for saying there was the evidence out there and they didn’t act upon it in the right way.” He tells me that Mukonyi asked the cabin crew on Flight 2069 for the male-to-female ratio among staff, the location of the cockpit and the time of the crew’s rest breaks.

“I guess there are paranoid states in which you can plan things in intricate detail? But if this had happened on an American carrier, I guarantee that action would have been taken against him. So that begs some questions. But it’s not something that I spend time thinking about…”

He shows me a letter he wrote in January 2001 to BA’s director of flight operations proposing “simple yet robust” systems and checks on passengers from ticket purchase to aircraft boarding, a complete review of security training given to flying staff, and a keypad entry system to the cockpit door: “a last barrier to unwelcome, uninvited guests”. He received a polite reply. He then shows me a letter from November 2001 in which he complained about “a year of frustration”: “My requests for information on what was happening with regard to the prosecution of Mukonyi and the security issues were ignored on many occasions.”

“We were instructed to operate the aircraft without the cockpit door locked. Closed. There is a big difference” – Bill Hagan

Around the edges of Hagan and Watson’s conversations is the question of the locked cockpit; the tension between the instructions of British Airways to allow a flow between cockpit and cabin to aid communication; and the concerns of pilots and passengers that it shouldn’t be so easy. Bryan Ferry told the Mail on Sunday that it was “madness” not to lock cockpit doors during flight. “It was forbidden,” Hagan tells me emphatically. “We were instructed to operate the aircraft without the door locked. Closed. There is a big difference.”

Nine months after Flight 2069, on 11 September 2001, terrorist cells in the United States stormed the cockpits of four American jets and hijacked them, crashing the planes into the World Trade Centre and the Pentagon. Seven days later, the locking of cockpits became international law. Though the doors of the 9/11 aircraft are said to have been locked, access was made using bolt cutters and threats to the flight crew. Reinforced doors with keypad codes became mandatory, as did the locking of doors during the entire flight.

On 7 May 2002, a report by the Civil Aviation Authority on behalf of the passengers of Flight 2069 was filed in the library of the House of Commons. It states: “The security and safety lessons from the incident for the travelling public have already been fully taken into account in the actions taken since the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001.”

It is not too much of a stretch to imagine a world in which the events onboard Flight 2069 were classified as a serious incident, and British Airways took on a leadership role in the aviation industry over the question of cockpit security. Jemima Khan tells me, “Bryan Ferry’s wife, Lucy, campaigned endlessly for improved cockpit security that year, and we were fobbed off.” She says that cuttings on Flight 2069 were found in the personal effects of one of the 9/11 hijackers trained in the Hamburg cell.

And it is not too much of a stretch to imagine, with four or five seconds’ difference, the aircraft having been lost with its cargo of millionaires and rock stars, and cockpit security becoming an urgent question to address in the international aviation scene in the early months of 2001. Would 9/11 have looked different? When I put it to Watson, he says: “If the plane had gone down, how would they know what had happened on it?” Hagan says: “I believe that the locking of cockpits would certainly have been brought in as law in Britain and the recommendations that did emerge from this would have been implemented as mandatory before 9/11. But the Americans do their own thing in every aspect of life – whether it would have made any difference there, I don’t know.”

Jemima Khan said that cuttings on Flight 2069 were found in the personal effects of one of the 9/11 hijackers trained in the Hamburg cell

This is the issue of the flight, as it lives on in the minds of those who survived it: how to measure the price of a disaster averted. Why it torments some of those involved when they came out alive; whether the instinct to seek evidence of cover-up makes any rational sense, or is a feature of trauma. Did 9/11, in changing the scope of potential disaster in the popular imagination, cast Flight 2069 in a sicklier light? Conspiracy theories, in their impulse to look for something bad at work in the machine, are preferable to the awful randomness of what might happen, or nearly happen. Perhaps it is natural for Bill Hagan, bearing the awful responsibility of captain but finding himself out of the cockpit when the attack began, to be poring over counter-factuals 25 years later. Others, like Watson, are at pains to see the story of Flight 2069 rationally, as a neutral “event” and an accident that did not happen – but there was nothing emotionally neutral about it. It was a confrontation with the deeply irrational, with madness, and with death, for everyone onboard.

Gifford Shaw and Clarke Bynum slept in the Hotel Intercontinental Nairobi with an armed guard outside their door: this was normal for Kenya, but unnerving for them. They aborted their mission to Uganda when the papers ran with a photo which clearly showed them both. “We were sure it was a terrorist attack,” Shaw tells me, “And there’s not many white guys in Kenya, and are we sure this is what we want to do?”

“I do believe the flight was our mission,” he continues. “That God somehow used two guys from little old Sumter, South Carolina, to save 398 people. Somebody had to fear no evil, to stand up and go in that cockpit. I told you there was a second person that went in before me, and no one has ever identified him? I believe that God sent His angel and helped us rescue that plane.”

The pair did rounds of press after 9/11, where their actions were compared to those of Todd Beamer, the American hero who led a group of people to overwhelm the hijackers of United 93. Hagan tells me, “The Americans greatly exaggerated the influence they had on the event. I did write to Gifford at some point and say, by the way, you didn’t actually remove Mukonyi from the controls!”

Does he know anything about the angel, the mysterious person in the cockpit?

“Four guys came in. A white south African, a man called John Keanes and the two missionaries. No angel.” When I asked Watson how Paul Mukonyi had sat so quietly for the two hours remaining to Nairobi, given the violence of the struggle, he replied, “Well, the guys had been stamping on his head!”

There were only two “security flights” for British Airways in 2001 – Israel and Belfast – meaning that the police monitored people getting on the plane. Nairobi was not on the watch list, although two years earlier, on 7 August 1998, 224 people had been killed, and over 4,000 injured, in bomb attacks on the American embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam. In December 2000, al-Qaeda was not in the common vocabulary, but the US and the UK had stepped up security operations in Kenya.

Upon landing in Nairobi, Mukonyi was taken by police and put under 24-hour terrorist watch, then placed in the medical care of the psychiatrist Frank Njenga. Njenga, speaking to me from Nairobi, recalls that the level of violence required to subdue and contain him “would have suggested to a lay person that this was a man on a terrorist mission”. He recalls a frightened individual tormented by fantasies of Arab gunmen, his own psychosis and the double horror of armed guards and men in white coats with needles. A Western winter in Lyon, he adds, hadn’t helped. Njenga says that Mukonyi’s mental illness had not been diagnosed until he came into his care.

Njenga was not just a jobbing doctor in A&E. “Full disclosure,” he tells me: he had led Kenya’s communications response to the Nairobi embassy bombings. “I used the same team for Flight 2069.” He held daily press conferences from the hospital canteen: “Working together with the media and giving them timely information changes a potential enemy into an ally.”

Once a case of mental illness was established for Mukonyi, Njenga says, people lost interest in the story: “The attention span of the public is barely longer than that of a flea.” I ask how it was that Mukonyi was released without charge and allowed to return to France, and Njenga says, “Today, as a doctor, I would not have been allowed to release him to his family. It would probably have required a judicial process.” What treatment did he receive? “I have to confess, I over-sedated him.” He claims not to have known Mukonyi before and has never heard from him since. I ask Njenga what he took away from the experience, and he says, rather oddly, that it has led him to question the mental health of pilots.

It is logical to fear a plane crash – less logical, you could argue, to get into a metal tube flown by someone else 40,000 feet in the sky and assume you are going to be OK. But there are feelings that those who have survived an airborne incident will struggle to put into words. In cockpit recordings of the moments before a fatal crash, some pilots can be heard talking quite normally. The captain of Alaska Airlines Flight 261, which ended up inverted in the sky before falling into the sea in January 2000, pointed out to his colleague, “At least upside down we’re flying.” I asked Phil Watson if pilots had any training in what to tell passengers over the PA system in the event of a crash. He said not: you’d have to figure it out for yourself. “It’s the lack of control. We are so used to being in control. As a passenger on an airliner, you’re not.”

Perhaps the true point of horror is something to do with the process of reckoning. Being alone with one’s consciousness, feeling intricate physical changes, trying to base judgements on inadequate knowledge and possibly, in doing so, facing death and the orphaning of children: this is the reality of being in a plane that might be going down. It is a private and lonely process, like death itself – you might hold each other’s fingers, but you can’t share the psychological reality. In the case of a jumbo jet accident, 400 “souls” – as the official reports still like to say – make this reckoning internally, and alone. Little wonder that survivors have reported docility on board when each is cocooned in a little circle of dawning.

Clarke Bynum sold his insurance practice soon after he returned to South Carolina and trained for the seminary. He was ready to go into the ministry when he passed away from cancer, aged 45, in 2007.

Bryan Ferry’s latest album is still playing on BA’s in-flight radio. He reformed Roxy Music the following year; surviving Flight 2069, he thinks, might have spurred him on. He only thinks about it in turbulence, when he gets what he describes as “short recollections” of being on the plane: “I think, ‘I’ve been through worse than this.’ But I find it testing. It’s another of those memories in life that get buried until someone talks about it. But to talk about it seems attention seeking. I like not to make a fuss. Life is worth making a fuss about. If you talk to the pilots, thank them again from me.”

Jemima Khan has been dyeing her hair since the flight because it turned grey with the shock. As the plane taxied down the runway, she was adamant that she was going to do something useful with her life; by the time she got to the luggage carousel she was bickering with her mother. “Maybe I should find some relief in the fact that when death comes you’re ready for it?” she tells me. But she was in her twenties, she says, “and afterwards I thought, I really, really don’t want to die”.

Her mother, Annabel Goldsmith, passed away while I was writing this piece. Two weeks after the flight, she wrote letters to Hagan and Watson, and invited them to dinner at her club. Ben Goldsmith went to the Amazon on holiday a few weeks after Flight 2069, and had a crash landing when a propeller fell off his plane.

Hagan had to retire, against his wishes, in 2002 because in those days, British Airways pilots could not fly beyond the age of 55. He flew for EasyJet instead: “Their attitude to safety is somewhere between extreme and paranoid,” he says approvingly. He still sleeps in short shifts of three or four hours a night.

His son Aidan was scared of air travel after the flight, and had to undergo hypnotherapy. He became a doctor and a fearless traveller, and moved to Australia.

“You know we lost Aidan?” says Hagan, looking up at me from his notes, wide eyed, when we met at Edinburgh airport. His son died at 29 in an accident at home in Melbourne. He later texts me: “It cannot be described but must be borne.”

I found Mukonyi on Facebook under a different name. I couldn’t see where he was living. I wrote to him saying that if we spoke, I would entirely preserve his privacy; that I wanted to give him the chance for his voice to be heard. When I checked for a reply, he had deleted his Facebook account.

As for the plane, tail number G-BNLM, it was inspected and found to be fit for purpose, largely because it had never flown too fast – a feature, Hagan thinks, of Watson’s flying skill. It flew to Dar es Salaam after it landed in Nairobi, and it flew for another 13 years.

G-BNLM was involved in two other near misses: relatively minor things, such as crashing into some lights at Miami when the crew missed a taxiway, and briefly passing within a mile of an Emirates Airbus in the sky at Heathrow – a “serious incident” which, unlike Flight 2069, received a full report from the Air Accidents Investigation Branch. These events did not lead to any crashes, though there is a universe in which they did. Look into the CVs of any of the big jets and you’ll find similar moments. Was this a fortunate plane, to have dodged fate? Are the survivors of Flight 2069 lucky to have survived, or unlucky to have boarded in the first place?

G-BNLM made its final flight, from Cardiff to California, on Monday 9 December 2013 at the age of 23. It came to rest in the desert at Victorville, a vast plane graveyard where the jets are ranged out like bones in the sun, and the aviation enthusiasts of the world can take photographs of them, at a distance, by poking their cameras through a perimeter fence.

[Further reading: The story of John Lennon’s bloodied glasses]

Content from our partnersRelated

Comments (0)