I still remember the ritual. Every September, without fail, my mum would drag me to the shoe shop for a new pair of Clarks. Black, sensible shoes. And the more I grew in years, the more mortified I became. Because in the playground hierarchy of the 1970s, these shoes were the opposite of cool. They were what your parents made you wear, what teachers approved of, what marked you as hopelessly conventional. Clarks were for kids whose mothers chose their clothes and tolerated no discussion. These were the opposite of "cool kid" shoes.

Which makes what happened next all the more remarkable.

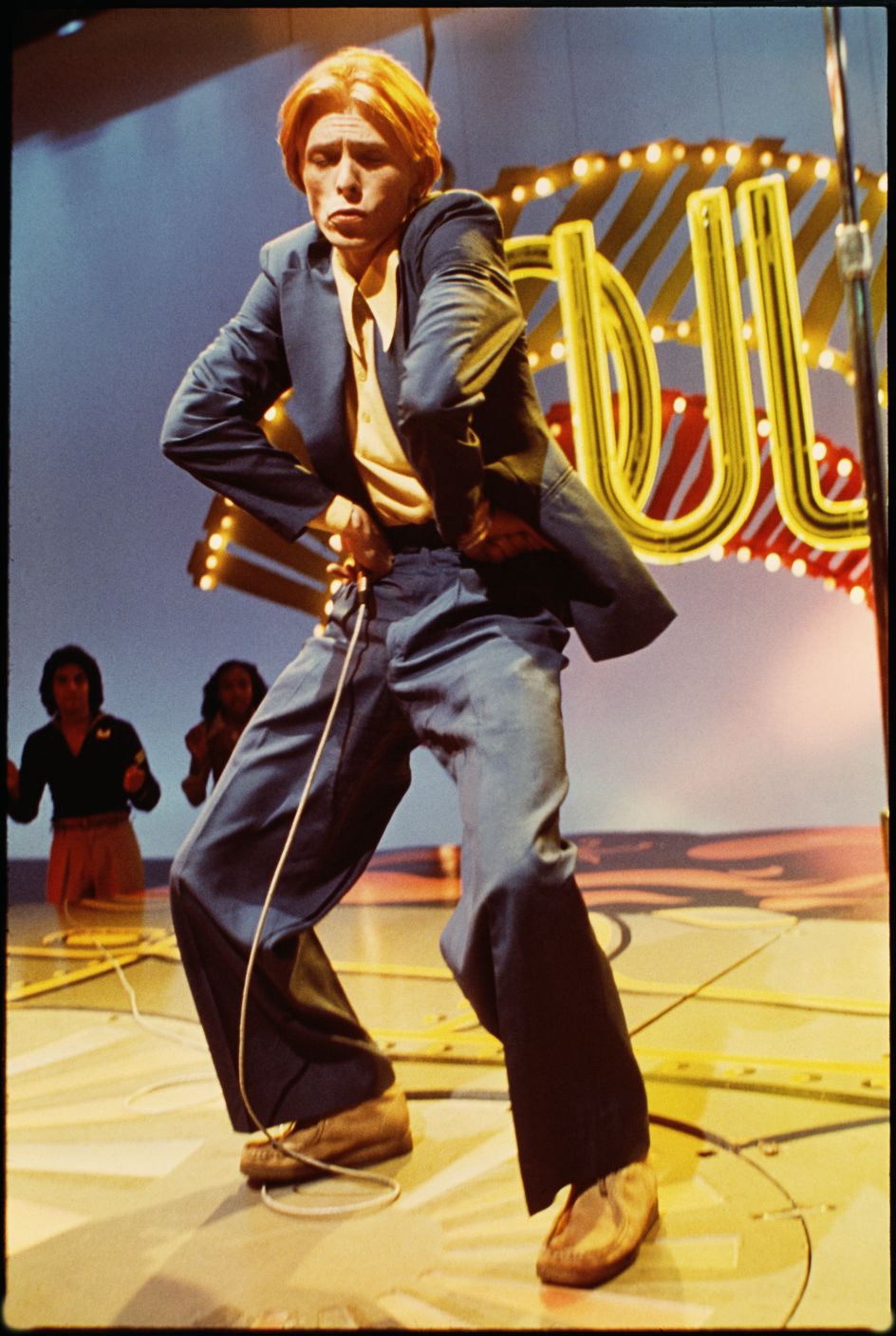

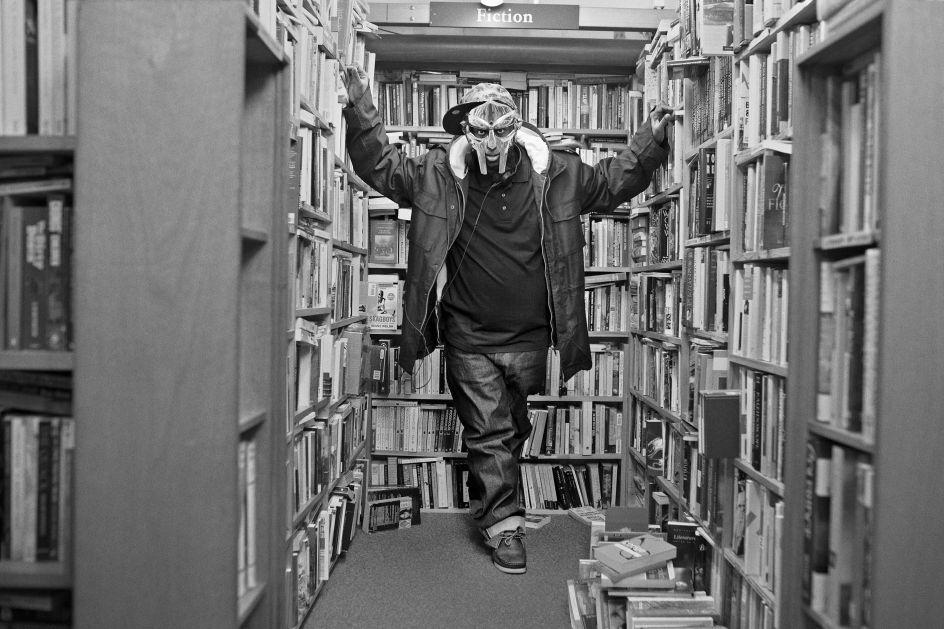

Somewhere between those dreaded back-to-school fittings and now, Clarks transformed from parental diktat into subcultural currency. David Bowie wore Wallabees on Soul Train. The Wu-Tang Clan name-checked Desert Boots. Jamaican dancehall artists elevated the brand to near-religious status. A shoe company founded by Quaker brothers in rural Somerset in 1825 became the footwear of choice for rebels, ravers and style innovators across five continents.

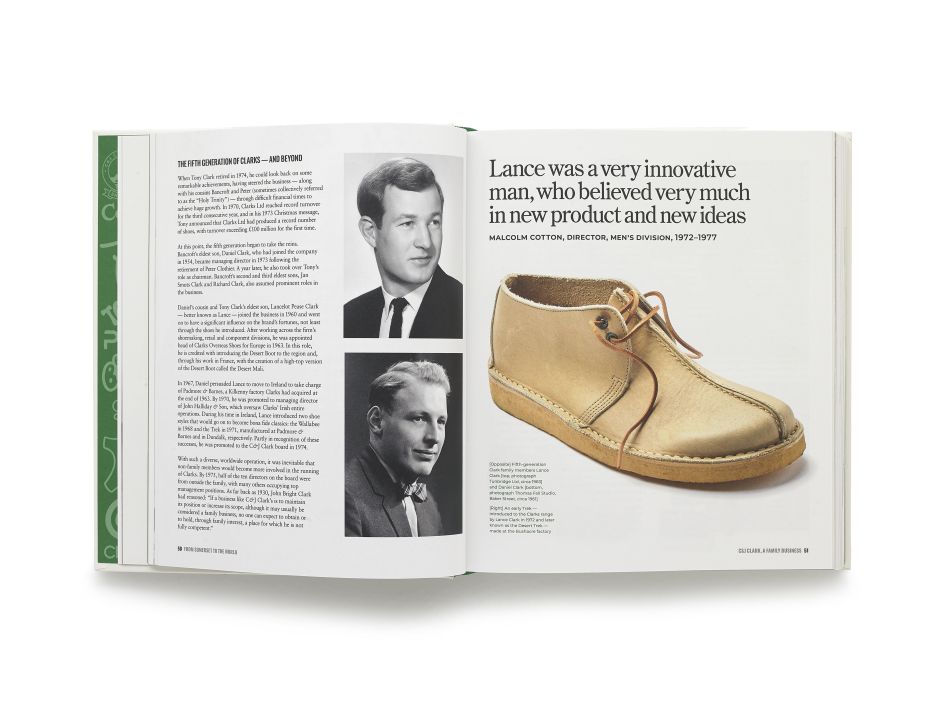

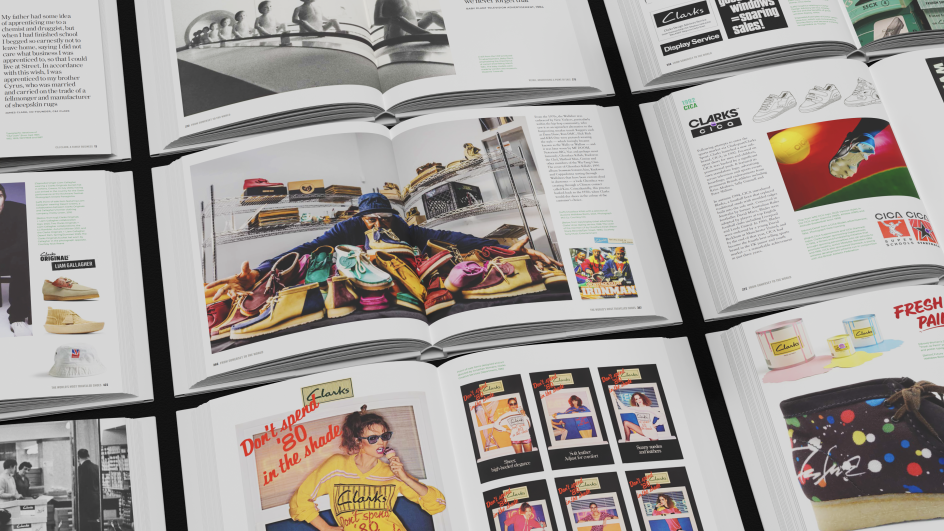

Unlikely journeyThis unlikely journey forms the heart of From Somerset to the World: Clarks A Visual History 1825–2025, a hefty new book from One Love Books that marks the brand's bicentennial. Written and designed by Alexander Newman, who previously chronicled the brand's Jamaican adoption in Clarks in Jamaica, this 448-page volume attempts something ambitious: explaining how a company rooted in Victorian propriety became synonymous with creative defiance.

The irony isn't lost on the author. His own interest grew from observing how Clarks "has been embraced across musical genres and subcultures"; communities that traditionally define themselves against mainstream conformity. Yet here was this establishment brand, born from sheepskin offcuts in a West Country village workshop, being co-opted by everyone from rude boys to hip-hop pioneers.

The book traces several origin stories for this cultural migration. One strand begins in Jamaica during the 1960s and 70s, where sharp-dressed rude boys adopted Clarks as part of their tailored image. The Desert Boot and Wallabee became dancehall essentials, worn by DJs and sound system operators as markers of both style and status. When Jamaican immigrants carried these cultural codes to New York, the shoes found new life in early hip-hop circles, where authenticity mattered more than flash.

Subverting associationsAnother transformation happened closer to home. British musicians in the 1970s and 80s began subverting Clarks' wholesome associations, turning childhood conformity into an adult statement. Perhaps no image captures this better than Bowie performing "Fame" in Wallabees on Soul Train in 1975 – the ultimate pop chameleon wearing the ultimate sensible shoe, somehow making both seem impossibly cool.

Oasis singer Liam Gallagher wearing a Clarks Originals bucket hat in Athens, Greece, 2000, shortly. Photograph Orestis Panagiotou. Courtesy Orestis Panagiotou/One Love Books

David Bowie wearing maple Wallabee Boots while performing his hit single “Fame” on Soul Train, Hollywood, Los Angeles, 1975. Photograph Andrew Kent. Courtesy Andrew Kent/One Love Books

Jamaican dancehall deejay Popcaan wearing Desert Boots at Coronation Market, Kingston, 2012. Photograph Martei Korley. Courtesy Martei Korley/One Love Books

Jamaican dancehall deejay Ninjaman (real name Desmond Ballentine) wearing Desert Boots, Kingston, 2015. Photograph Constanze Han. Courtesy Constanze Han/One Love Books

The book benefits from unprecedented access to Clarks' archives, revealing forgotten advertising campaigns, early design experiments, and the Quaker values of simplicity and integrity that shaped the company's approach. There's also a foreword from Jony Ive, who admits his "relationship with Clarks truly blossomed" when he discovered Wallabees at art school and has been wearing them "pretty much ever since". Coming from someone who helped define Apple's design language, that's quite the endorsement.

For creatives, there's a fascinating case study here about brand evolution. Clarks never chased cool; cool found them. They stuck to making well-constructed, unpretentious footwear while cultures around them shifted and reinterpreted what those shoes meant. The Desert Boot, designed in 1950 by Nathan Clark after observing footwear in a Cairo bazaar, remained essentially unchanged while its cultural significance mutated from practical comfort to mod staple to indie uniform.

Rapper/producer MF DOOM wearing his Clarks Originals collaboration, the Wallabee Doom, at Skoob Books, Bloomsbury, London, 2014. Photograph Martin Zähringer. Courtesy Martin Zähringer/One Love Books

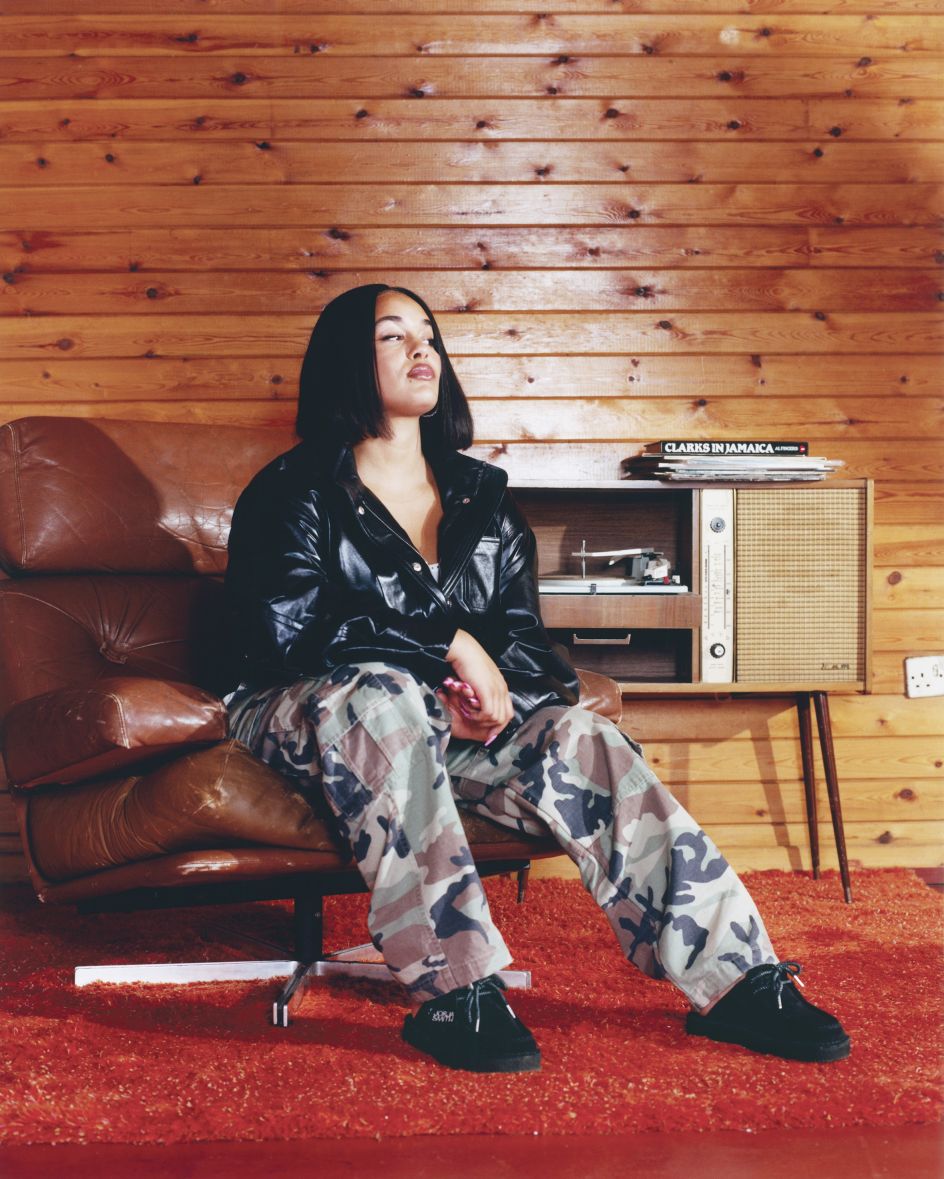

British singer Jorja Smith wearing the Clarks Desert Nomad Mule, a shoe Smith co-designed with Clarks, made from a sustainable suede and featuring compostable thread, 2023. Photograph Kaj Jefferies. Courtesy Kaj Jefferies/One Love Books

British singer and actress Mahalia wearing Torhill during the photoshoot for her album, IRL (Atlantic Records, 2023). Photograph Sirui Ma. Courtesy Sirui Ma/One Love Books

Perhaps most interesting is how different communities claimed Clarks simultaneously, creating parallel meanings. While British teenagers wore them to look vaguely bohemian, Jamaican artists were investing them with deeper cultural significance. Tokyo street style, meanwhile, adopted them as a form of imported authenticity. Each group saw something different in the same crepe sole.

What emerges is less a straightforward corporate history than a study in cultural alchemy. The transformation from my childhood embarrassment to Liam Gallagher's Britpop uniform to Vybz Kartel's dancehall essential wasn't planned by marketing departments. It happened because creative communities recognised something genuinely different in Clarks' unfussy functionality. And let's not forget: this is a rare quality in an industry obsessed with performance, innovation and planned obsolescence.

Design-led approachThe book's own design-led approach suits the material, making it function as both an archive and a visual argument. Seeing a young Florence Welch in Clarks at Glastonbury alongside images of 1970s Jamaican album covers makes the case more eloquently than any text could: this isn't just about shoes, it's about how design objects accumulate meaning through use and reuse across cultures.

Ultimately, in an era of relentless trend cycles and algorithmic recommendations, there's something quite refreshing about a brand that's spent 200 years making essentially the same things well. Those playground Clarks I resented weren't trying to be anything other than honest, well-made shoes. That they became symbols of creativity and cool says something profound about the value of choosing a path and following it consistently.

Comments (0)