Hi all,

I just got back from Davos, and this year was different. The AI discussion was practical – CEOs asking each other what’s actually happening with their workforces, which skills matter now. At the same time, I saw leaders struggling to name the deeper shifts reshaping our societies. Mark Carney came closest, and in this week’s essay I pick up his argument and extend it through the Exponential View lens.

Enjoy!

Mark Carney delivered a speech that will echo for a long time, about “the end of a pleasant fiction and the beginning of a harsh reality.” Carney was talking about treaties and trade but the fictions unravelling go much deeper.

Between 2010 and 2017, three fundamental inputs to human progress – energy, intelligence, and biology – crossed a threshold. Each moved from extraction to learning, from “find it and control it” to “build it and improve it.” This is not a small shift. It is an upgrade to the operating system of civilization. For most of history, humanity ran on what I call the Scarcity OS – resources are limited, so the game is about finding them, controlling them, defending your share. This changed with the three crossings. As I write in my essay this weekend:

In each of the three crossings, a fundamental input to human flourishing moved from a regime of extraction, where the resource is fixed, contested, and depleting, to a regime of learning curves, where the resource improves with investment and scales with production.

At Davos, I saw three responses: the Hoarder who concludes the game is zero-sum (guess who), the Manager who tries to patch the system (Carney), and the Builder who sees that the pie is growing and the game is not about dividing but creating more. The loudest voices in public right now are hoarders, the most respectable are managers, and the builders are too busy building to fight the political battle. The invitation of this moment? Not to mourn the fictions, but to ask: what was I actually doing that mattered, and how much more of it can I do now?

Full reflections in this week’s essay:

For most of history, humanity ran on what I call the Scarcity OS. Resources are limited in this system so the game is about finding them, controlling them, and defending your share. This logic shaped everything – our institutions, our economics, our social structures, our sense of what’s possible.

OpenAI was the dominant player in the chatbot economy, but we’re in the agent economy now. This economy will be huge, arguably thousands of times bigger but it’s an area OpenAI is currently not winning: Anthropic is. Claude Code reached a $1 billion run rate within six months, likely even higher after its Christmas social media storm.

OpenAI is still looking for other revenue pathways. In February, ChatGPT will start showing ads to its 900 million users – betting more on network effects than pure token volume. This could backfire, though. At Davos, Demis Hassabis said he was “surprised” by the decision and that Google had “no plans” to run ads in Gemini. In his view, AI assistants act on behalf of the user; but when your agent has third-party interests, it’s not your agent anymore.

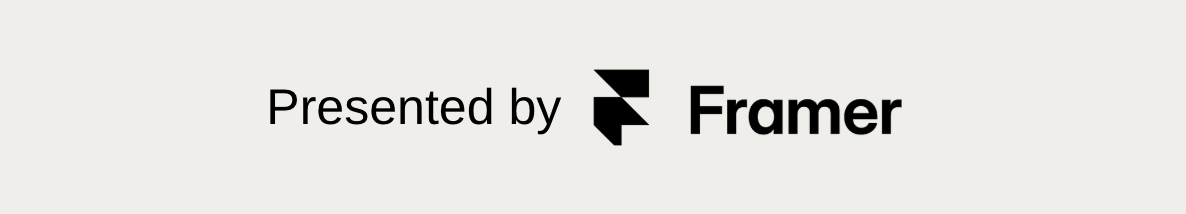

OpenAI reported that its revenue scales in line with compute; they need a lot of energy and funding.

OpenAI reported that its revenue scales in line with compute; they need a lot of energy and funding.Sarah Friar, OpenAI’s CFO, wants maximum optionality and one of the bets will be taking profit-sharing stakes in discoveries made using their technology. In drug discovery, for example, OpenAI could take a “license to the drug that is discovered,” essentially claiming royalties on customer breakthroughs. Both Anthropic and Google are already there and have arguably shown more for it. Google’s Isomorphic Labs, built on Nobel Prize-winning AlphaFold technology, already has ~$3 billion in pharma partnerships with Eli Lilly and Novartis, and is entering human clinical trials for AI-designed drugs this year. Then, there are OpenAI’s hardware ambitions.

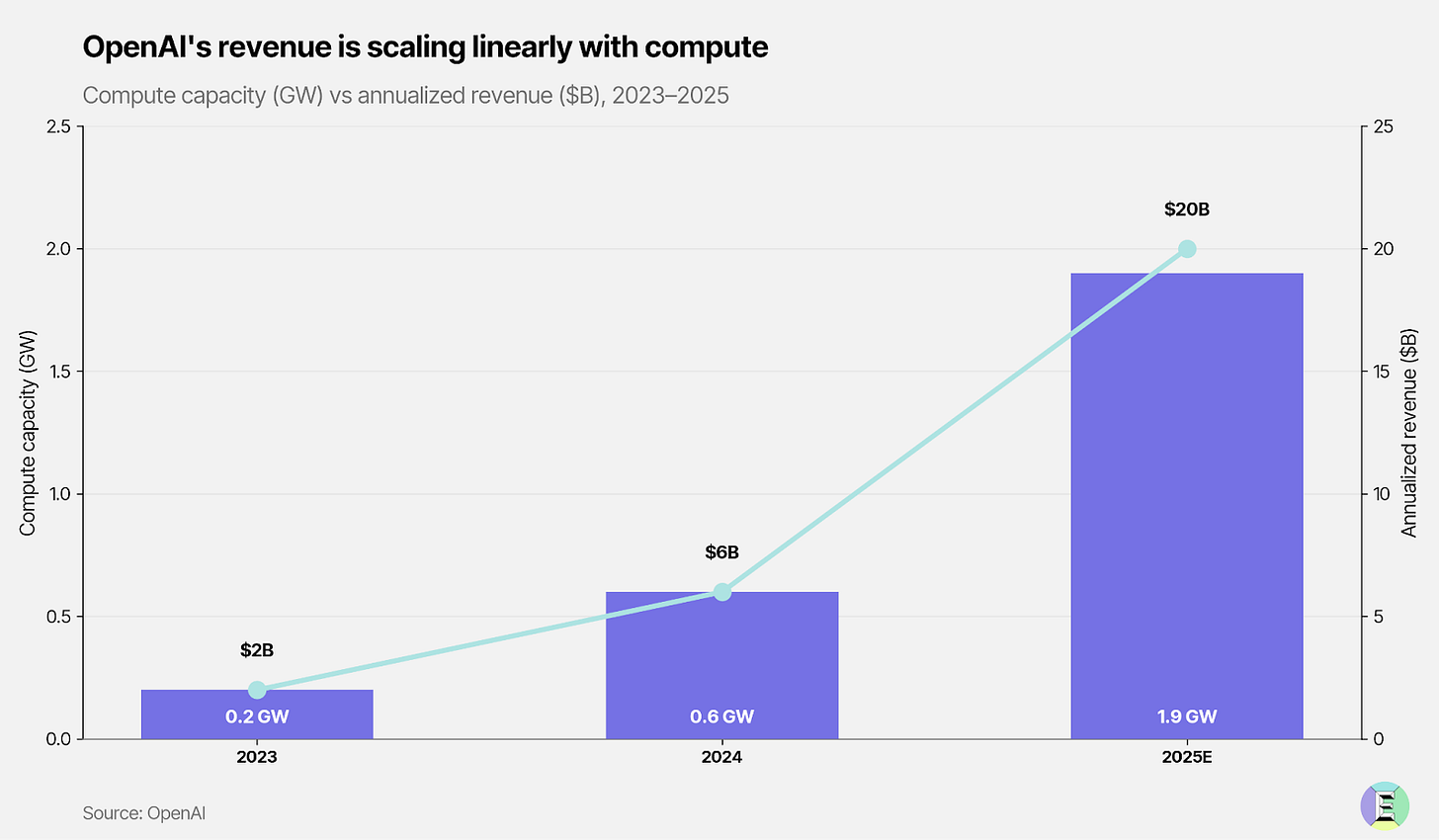

OpenAI needs a new alpha. Their main advantage was being the first mover. But the alpha has shifted from models to agents and there, Anthropic moved first properly with Claude Code. It’s hard to see how OpenAI can sustain its projection of $110 billion in free cash outflow through 2028 in a market it isn’t clearly winning. Anthropic, meanwhile, projects burning only a tenth of what OpenAI will before turning cashflow positive in 2027 (although their cloud costs for running models ended up 23% higher in 2025 than forecast).

Perhaps this is why Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic, told me at Davos that research-led AI companies like Anthropic and Google will succeed going forward. Researchers generate the alpha, and research requires time, patience and not a lot of pressure from your product team. OpenAI has built its timeline and product pressure. This has an impact on the culture and talent. Jerry Tworek, the reasoning architect behind o1, departed recently to do research he felt like he couldn’t do at OpenAI (more in this great conversation with Ashlee Vance and Kylie Robison).

None of this means that OpenAI is out for the count. They still have 900 million users, $20 billion in revenue, and Stargate. But they’re currently in a more perilous position than the competition.

See also:

A MESSAGE FROM OUR SPONSOR

First impressions matter. With Framer, early-stage founders can launch a beautiful, production-ready site in hours — no dev team, no hassle.

Pre-seed and seed-stage startups new to Framer will get:

One year free: Save $360 with a full year of Framer Pro, free for early-stage startups.

No code, no delays: Launch a polished site in hours, not weeks, without technical hiring.

Built to grow: Scale your site from MVP to full product with CMS, analytics, and AI localization.

Join YC-backed founders: Hundreds of top startups are already building on Framer.

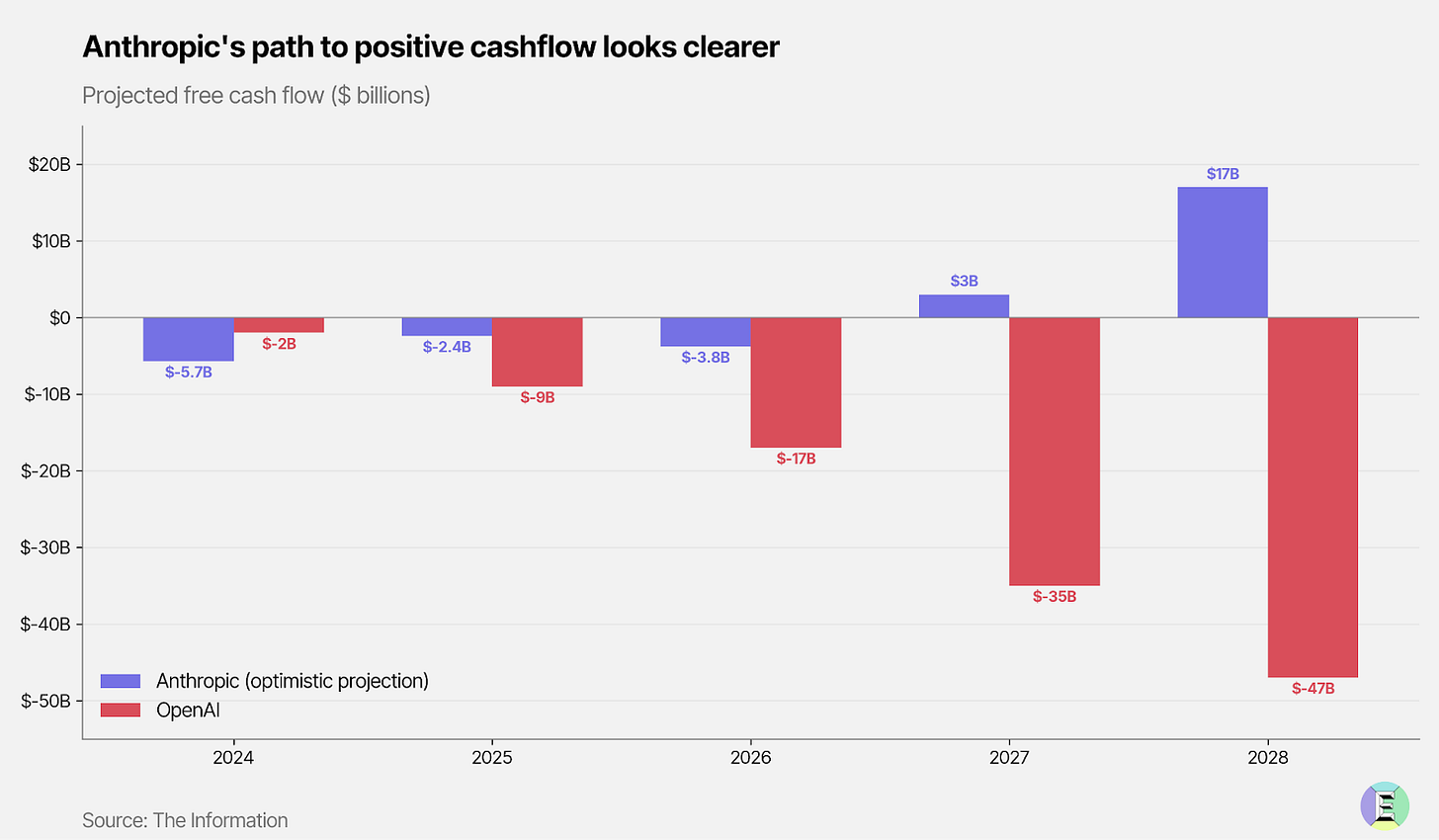

The conventional story treats alignment as a tax on capability. Labs face a prisoner’s dilemma: race fast or slow down for safety while someone else beats you to market. At Davos, Dario Amodei said if it were only Demis and him, they could agree to move slowly. But there are other players. Demis told me the same after dinner.

This framing might suggest to some that we’re in a race toward misaligned superintelligence. But I’ve noticed something in recent dynamics that makes me more hopeful. A coordination mechanism exists and paradoxically, it runs through the market.

When users deploy an agent with file system access and code execution, they cede control. An agent with full permissions can corrupt your computer and exfiltrate secrets. But to use agents to their full potential, you have to grant such permissions. You have to let them rip.

Dean W. Ball, a Senior Fellow at the Foundation for American Innovation, noticed that the only lab that lets AI agents take over your entire computer is the “safety-focused” lab, Anthropic. OpenAI’s Codex and Gemini CLI seek permission more often. Why would the safety-focused lab allow models to do the most dangerous thing they’re currently capable of? Because their investment in alignment produced a model that can be trusted with autonomy.

Meanwhile, the one company whose models have become more misaligned over time, xAI, has encountered deepfake scandals, regulatory attention, and enterprise users unwilling to deploy for consequential work.

Alignment generates trust, trust enables autonomy, and autonomy unlocks market value. The most aligned model becomes the most productive model because of the safety investment.

See also:

Anthropic researchers have discovered the “Assistant Axis,” the area of an LLM that represents the default helpful persona, and introduced a method to prevent the AI from drifting into harmful personas.

Signal Foundation President Meredith Whittaker warns that root-level access required by autonomous AI agents compromises the security integrity of encrypted applications. The deep system integration creates a single point of failure.

Robotics has two of Exponential View’s favourite forces working for it: scaling laws and Wright’s law. In this beautiful essay worth your time, software engineer Jacob Rintamaki shows how those dynamics push robotics toward becoming general-purpose – and doing so much faster than most people expect.

Robotics needs a lot of data. Vision-language-action models are expected to benefit from scaling laws similar to LLMs. The problem is data scarcity: language has a lot of data, but vision-language-action data is scarce. Robotics is roughly at the GPT-2 stage of development. But each robot that starts working in the real world becomes a data generator for the specific actions it performs – this creates a flywheel. More deployed robots generate more varied action data. The next generation of models absorbs this variety and becomes more capable of unlocking larger markets worth serving. That’s scaling laws. And Wright’s law compounds the effect: each doubling of cumulative production will drive down costs. Already, the cheapest humanoid robots today cost only $5,000 per unit. Rintamaki argues they’ll eventually cost “closer to an iPhone than a car”; they require fewer raw materials than vehicles and need no safety certifications for 100mph travel.

AI datacenter construction will kick off the flywheels. Post-shell work (installing HVAC systems and running cables) is 30-40% of construction costs and is repetitive enough for current robotics capabilities. The buyers are sophisticated, the environments standardised, and the labour genuinely scarce: electricians and construction crews are in short supply.

See also, World Labs launched the World API for generating explorable 3D worlds from text and images programmatically. A potential training environment for robots.

Comments (0)