Recently, my father sent me a picture of my cousin Ariane’s christening. In it, I was fourteen or so, her godmother. Another cousin was her godfather. We were all very young. We stood with the priest around the baptismal font, in our baptismal finery. Ariane was screaming her tiny, adorable head off in the priest’s arms. At first, I didn’t recognize myself in the photo. I remembered myself as much bigger. For nearly two years, I had been gaining weight and no one understood why. I knew, of course. I had made a choice to build a wall of flesh around myself, to make myself safe after being desperately unsafe. My family was panicked. They immediately shifted into overreaction, trying to solve the problem of my body but my body was not actually a problem, at least not to me.

That’s why, in the decades since, I am impossibly large in my recollections. That’s how extravagantly the people around me reacted to my changing body. The picture, though, seeing it so many years later, was startling. It was evidence that the story I told myself for so long—a story architected by people who meant well but caused harm nonetheless—was not the truth. Certainly, I looked awkward because I was wearing a cream-colored, satiny dress with boxy shoulders and I hated wearing dresses. They looked terrible on me, like I was playing dress-up with a very different girl’s wardrobe. I sported a weird haircut because I had no sense of style yet. I simply wanted to be invisible. My body was incidental, a vessel for my fractured mind. But, in reality, I was cute. I had a baby face. I was not fat, at all. So many years later, in a much larger body, I would love to be that size again. I would revel in it. And I would love to have recognized, back then, that there was nothing wrong with me at any size.

I am my father’s only daughter and while my brothers and I were each our parents’ favorites in different ways, I am his favorite. He had dreams for me as his only daughter, his American girl, and most of those dreams conflicted with who I actually was. This happens between parents and children. Even though he never explicitly articulated his dreams I knew he wanted me to be girly and popular. Maybe he wanted me to be a cheerleader, bright and bubbly, pretty in pink. Instead, he got a shy, quiet introvert who spent most of her time with her head in a book. This wasn’t necessarily a bad thing and he encouraged my reading and eventually, my writing. But as the only girl with two brothers, I was far more inclined to be something of a tomboy. I eschewed overly feminine things, and while people assumed it was because I was a tomboy, that wasn’t really the case. I eschewed anything that would bring attention to myself. I took comfort in oversized shirts and sweaters, baggy pants, anything that would shroud my ever-expanding body.

During the years when I was supposed to be taking an interest in boys, going on dates, maybe embarking on a sweet relationship with a first love, there was no one in my vicinity who was even remotely interested. I had crushes that were, mostly, silly affectations because I felt like I was supposed to have a crush and yearn dramatically. If I doodled some boy’s name on my notebook and drew hearts while I gazed into the distance, daydreaming, maybe I would become a real girl. Unfortunately, I was never that good at doing what was expected of me when it came to social graces.

When you are fat in a fatphobic world, you tend to live in a peculiar state of longing.

What my real life lacked, I more than compensated for with my imagination. In truth, I hated boys—their bravado and the tangy smell they carried in their skin. I hated their loud voices and growing muscles and how easily they took up space as if it was their due. But I wanted to be like the other girls, the normal girls. I wanted boys to want me before I understood that really, I wanted girls to want me. I wanted to wear a letterman jacket, have a boy hold my hand, ask me out on a date, recognize that I was a girl too, with a hungry girl heart. I succeeded in my desire to be invisible. The attention I did get from boys and then men was always furtive, often sleazy, and very transactional. They took and I gave and I told myself it was enough.

When you are fat in a fatphobic world, you tend to live in a peculiar state of longing, a state of perpetual anticipation, making yourself promises about all the things you will do when.

WYou plan your life around the bounty that awaits when you lose enough weight to find a loving partner, to get a good job, to travel abroad, to visit parents without intense anxiety, to make everyone happy, to make yourself happy. This fraught limbo is how I lived through my teens, my twenties, my thirties. Decades of waiting go by until you reach middle age and are forced to ask yourself, “When will I really start living?” Even once I started to embrace body neutrality in my forties, I nurtured this stasis, as if life would only truly begin when I was the right size and what a short life it would be. I wasted so much time I will never get back. There was never going to be a right size so long as I believed I was the problem. And oh, how I believed that, into the marrow of my bones. I couldn’t believe otherwise no matter how hard I tried.

As women, we are told relentlessly, in so many different ways, that youth and beauty and thinness are currency. It is how we communicate our value to the world. As we age, that currency becomes less powerful and then, we simply fade from relevance, left, hopefully, in peace to enjoy our dotage. If you don’t meet the standards of conventional attraction, your currency is less powerful. And when you are fat, when you inhabit an unruly body, you have no currency at all. I didn’t always know this but once I learned, I was a perfect student.

For years, I also told myself that when I emerged from this stasis, when I was the right size, I would finally be a real woman, where a real woman was thin, beautiful, desired—someone who had currency, someone who would be able to enjoy womanly things, be seen as and treated like a woman, even if I also had to deal with the challenges of womanhood with which most other women contend.

I had all these yearnings, but I was also furious with myself for wanting things that intellectually, at least, I found reductive, problematic, or misogynistic. That’s the terrible bind of body tyranny. We are taught to want the things that harm us most.

What I really mean is that I always hoped to be treated with care, with tenderness. I hoped people might recognize I could be as delicate as I am strong. I hoped people might truly see me. But fatness renders women genderless or, at least, that has been my experience of fatness. Fatness renders women not only invisible but also inconvenient, always in the way, always taking up too much space. People will stare too hard, make their snide little comments, sigh with impatience when I am walking too slowly, make it clear in one way or another that for them, my body is a problem, and a serious one at that.

As women, we are told relentlessly, in so many different ways, that youth and beauty and thinness are currency.

Men have treated me like one of the guys, a person so far beyond the reach of their desires as to be just like them. Women have treated me like one of the guys, a person so far beyond their understanding of womanhood as to be an entirely different species.

All these years, I thought I still had time to enjoy what were supposed to be the best years of my life. I thought I still had time to be a woman. And then, year by year, many of the things I wanted or at least thought I wanted for myself, all that possibility fell away. This is who I am, this is the body I am living in, there is a lot of life left to live, but there are certain experiences I will never have.

In some ways, I never got the chance to be a woman, but this is not a story of regret.

I am fifty years old but I’ve always been a late bloomer. Even as I stumbled into my teenage years, I was a very young thirteen, fourteen, even fifteen. I got my period later than most girls. I was at boarding school and too shy and self-conscious to ask my mom for guidance, so I went to the Woolworth’s in town and browsed the “feminine hygiene” aisle for a very long time, carefully reading the packages of menstrual pads and tampons. It all seemed awkward and uncomfortable. When I got back to my dorm with a box of tampons, I hid in a bathroom stall and pored over the folded instructions several times. This was before YouTube and Wikipedia. There were no online forums to consult for advice on how to actually use a tampon. It never crossed my mind to ask my mother, who was rather hands off when it came to all things womanhood. The first attempts were awkward and a little painful but eventually, I figured it out and a long, bloody misadventure began.

Even after that, I remained a late bloomer. I didn’t grow to my current height until my very late teens, well after everyone assumed I was done growing. I didn’t finish graduate school until I was thirty-six. I married in my late forties. For whatever reason, I have always taken a lot of time to become more of myself. And so, when it came to menopause, I expected the worst—having to deal with my period until my late sixties or something equally nightmarish. Once again, I didn’t know what to expect. My mother, who went through menopause in her fifties, was pretty circumspect about the experience. She didn’t have any of the typical lamentations you might expect. I heard little of hot flashes or all the other bodily changes many women experience. Both of my grandmothers had died many years earlier. Many of my friends were just starting their families in their early forties so menopause was not really on their radar. My wife had gone through menopause years before we met and her experience of it was relatively brief and not terribly disruptive. And, because I had so rarely, throughout my life, been seen or treated as a woman, I sort of assumed that menopause would simply pass me by, the way so many other things had.

That’s the terrible bind of body tyranny. We are taught to want the things that harm us most.

The only thing I knew for sure was that with menopause, I would no longer have to deal with my period and that felt like winning the lottery. Every single month, for nearly thirty-five years, I would start to feel despondent and irritable. My breasts became tender. My sex drive was out of control. I was incredibly tired and wanted to sleep all the time. I’d wonder what the hell was going on and start to worry that something might really be wrong. And then, my period would appear and I would realize that all of those weird symptoms were, simply, warning signs. Then, the next month, I started to feel despondent and irritable. My breasts became tender. You get the picture. Sometimes I kept track, first in a paper calendar, later with the Notes app on my phone, and eventually with a series of fertility apps. If I tracked my physical realities assiduously, I might become a real, responsible adult, in command of what little womanhood I had. For decades, I never really learned that my body was always trying to tell me something.

This is to say, I hated my period. I really did. It was inconvenient. I often had really heavy periods. I mean really heavy. At times, I worried I would simply bleed out. I wondered where the hell all that blood was coming from. I used an extraordinary number of very big, uncomfortable tampons. I didn’t have debilitating cramps or some of the other challenges people with uteruses must contend with, which was, I suppose, a small blessing.

In my mid-forties, my period suddenly became erratic, not that it had ever been particularly disciplined. I would get my period and then it would disappear for a few months. I’d have a delightfully abbreviated period, maybe two days, which absolutely thrilled me. A few months later, I would have a three-week period. Then I would get my period four times in a single month at which point I despaired that I would never, ever stop bleeding. Sometimes, I would start spotting, as if my period was just dipping her toes in the proverbial waters to see if she felt like making a full appearance. As my period came less and less frequently, I started to believe I was finally done with all of that and then yet again she would show up, taunting me, as if to say, “You wish!”

Each time I got my period after three or four months of absence, I was overcome by a wave of frustration that there was no way of knowing which period would be my last. I turned to the internet because my primary physician is a zygote, and I couldn’t bring myself to ask her what to expect when I was expecting to never be able to expect again. Dr. Google offered a bewildering range of information about menopause, its symptoms, and what to anticipate. A lot of that information was contradictory and wildly inadequate, a reminder that the medical establishment treats women’s bodies as mysterious and unknowable. Whatever goes on in our bodies is none of their concern, unless, of course, we are pregnant, and then for nine months, in certain states, our bodies are not only knowable but legislated, public property.

I knew menopause would happen, but I assumed it wasn’t going to affect me the way it affected other women because I spent so much of my life exiled to the periphery of traditional womanhood. I watched countless depictions of menopause in film and television that showed women worrying about their skin and their libido and hormone levels. I took in all the exaggerated depictions of women in the throes of hot flashes, drenched in sweat, shoving their heads into freezers or sitting in front of oscillating fans looking for respite from an inescapable heat. In Sex and the City 2, noted sex enthusiast Samantha Jones brought a small valise of hormones, supplements, and other elixirs she used to stave off the encroachment of “the change” and to “trick my body into thinking it’s younger.”

When I experienced my first hot flash, it defied everything I had ever imagined. A small fire was burning inside of me and it grew hotter and hotter until I was desperate to extinguish roaring flames I could not reach. When the heat subsided, I never wanted to experience a hot flash ever again. I did, of course, experience more hot flashes, but there was no set pattern. They would happen in the middle of class, while I was teaching. They would happen in the middle of the night as I tore the sheets off and tried to find pockets of cool air. My wife sometimes experienced sympathy hot flashes, drenched in sweat beside me.

The medical establishment treats women’s bodies as mysterious and unknowable.

Other than that, the onset of menopause or perimenopause, who can know, was fairly unremarkable. My hair thinned a bit, but because I have a thick head of hair it wasn’t alarming. I didn’t feel like my hormone levels were changing. I felt mostly like myself. There was some sadness because the likelihood of having a child—the old-fashioned way, with a donor and my wife wielding a turkey baster—had narrowed to a tiny sliver, but there were other options. It would be fine, no matter what. I had always known that while I would enjoy being a parent, I wouldn’t feel like I lived less of a life if I wasn’t one.

Menopause is, technically, a year after your last period so I don’t know if I am in menopause. I’m hovering in yet another stasis, wondering if a significant part of my life is over.

For years, I’ve been dealing with writer’s block though that is far too mild a term to describe it. One day, I was writing with ease, looking forward to getting back to the page each day, and the next, it was all gone. I would stare at an open Word file, the cursor slowly blinking, my fingers hovering above the keys as I willed them to make something out of nothing.

What had once been joyful instantly became misery. It was a breathtaking shock. I have always loved writing and I have always wanted to be a writer. Writing and reading have been the constants in my life so to lose them unmoored me completely. And because I was still publishing work, no one understood or believed me when I expressed how severely blocked I was, creatively. Technically, yes, I was writing but it wasn’t my best. It came in fits and spurts. I hated having to share work with anyone, and doubted every word I wrote, every idea I tried to develop. My writing was stilted, flat, drab. It stunned me, really, that I was capable of producing such inadequate, lifeless prose. The longer it went on, the harder it became to write. I’m stubborn, so I kept at it, but it was always squeezing absolutely nothing from obdurate stone. I felt utterly depleted and embarrassed.

I stopped trusting my judgment, my intelligence, my voice. I lost all faith in myself as a writer. I started making alternative plans for the future, one where I could no longer credibly identify as a writer. It was grim, but I so deeply believed I could no longer write that I needed to find a different way forward. On a more practical note, I needed to be able to pay my mortgage and student loans and meet my other financial obligations. At first this was all very annoying, and then it was sad, and then it was terrifying as panic set in. Deadlines came and went for days, weeks, months, and in some cases several years. The patience of my editors frayed to almost nothing and I understood. My patience with myself was similarly frayed. I felt so much shame, I thought I might drown in it.

So much of who I am is entwined with writing. I’m not talking about the public face of the work—the publications, the tours and events, the accolades. I can live without that. My original dream of being a writer was simple because I didn’t know what to dream beyond wanting to write good books and maybe have them published. All I needed was to be able to hold onto that dream, but as these fallow years stretched on, I tried to accept that I might lose even that. Almost every night, I stared at the ceiling asking myself, “Who am I if I am not a writer?” It was a question I could not answer then or now.

Almost every night, I stared at the ceiling asking myself, ‘Who am I if I am not a writer?’

And then, one day I was talking with a friend over dinner. We were on a double date with our spouses, a warm Los Angeles evening, sitting outside. The din of a busy restaurant surrounded us. We had nice cocktails. Great music was playing. My friend was talking about how the worst part of menopause was the brain fog. It affected almost everything she did on a daily basis; it was only with time and various treatments that the fog started to clear. It felt like a lightning bolt struck our table. I immediately peppered my friend with questions because I did not know brain fog could be a symptom of menopause. When I got home, I immediately started searching for more information and learned that many, many women deal with losing focus and becoming easily distracted and having no ability to concentrate and forgetting the very things we know for sure. Finally, I found a lifeline, the idea that maybe my overwhelming writer’s block was not a personal failing rendering me beyond redemption, that maybe, the source of what ailed me was, at least in part, beyond my control and would not last forever.

It is a bitter thing, to have spent most of your life in a body you’ve been told you are supposed to hate, a body that is considered a placeholder for the real, more appropriate body you’re meant to live in. You keep waiting for your real life to begin on that magical day when you finally discipline your body into what society prefers it to be. But sometimes, you get lucky. You stop waiting and start living. As I’ve tumbled into menopause, I’m supposed to believe my womanhood is ending but instead, I have been handed a new beginning.

Nearly six years ago, a woman named Debbie persisted in pursuing me until I finally accepted her invitation to go on a proper date. We had a lovely time and then there was a second date and a third and then we were officially girlfriends. We did long distance until the pandemic began. As we hunkered down in Los Angeles, we grew even closer, thriving with so much time together, just us and, before long, our pandemic puppy Max. We got engaged and we eloped under a plastic chuppah in Encino. We go on all kinds of adventures, all around the world. We’ve seen the mighty glaciers in Antarctica. On the steppes of Mongolia, we had the honor of sitting with a shaman who brought forth a spirit. In Uzbekistan, we stood at the center of Registan Square, in awe of the Islamic architecture around us. At a vineyard in Tuscany, we opened the windows to our hotel room and had a small picnic with a good bottle of wine, some cheese and cured meat, and watched Avengers: Endgame on an iPad after a long day of touristing. And many nights, we just sit on our couch at home, watching television and working away on our laptops. It sounds like a fairy tale and, in truth, it absolutely is. There is no more waiting. When is now.

NAnother truth is that this story is only a fairy tale because I started believing that maybe, just maybe, I was worthy of living a fairy tale, in this body, exactly as I am. My forties had already been pretty good when we met but then my wife made them extraordinary. I am no longer living a life suspended. I am, simply, living. For decades, it turns out, I wasn’t really yearning to be treated like a woman. I was yearning to be treated like a human being. For the first time in my life, I am experiencing unconditional kindness, genuinely reciprocated passion, truly gentle touch. It was so startling, in the early going, as to almost be uncomfortable. Sometimes, it still is but I am more than willing to tolerate the discomfort. It’s not that I experienced violence at the hands of previous lovers. They were simply careless. I allowed them to be. They did not understand me as someone to be handled with care, someone worthy of being handled with care. I did not understand myself as someone to be handled with care. I do not know if I am at the beginning or the middle or the end of menopause, but “the change” has changed me, nonetheless.

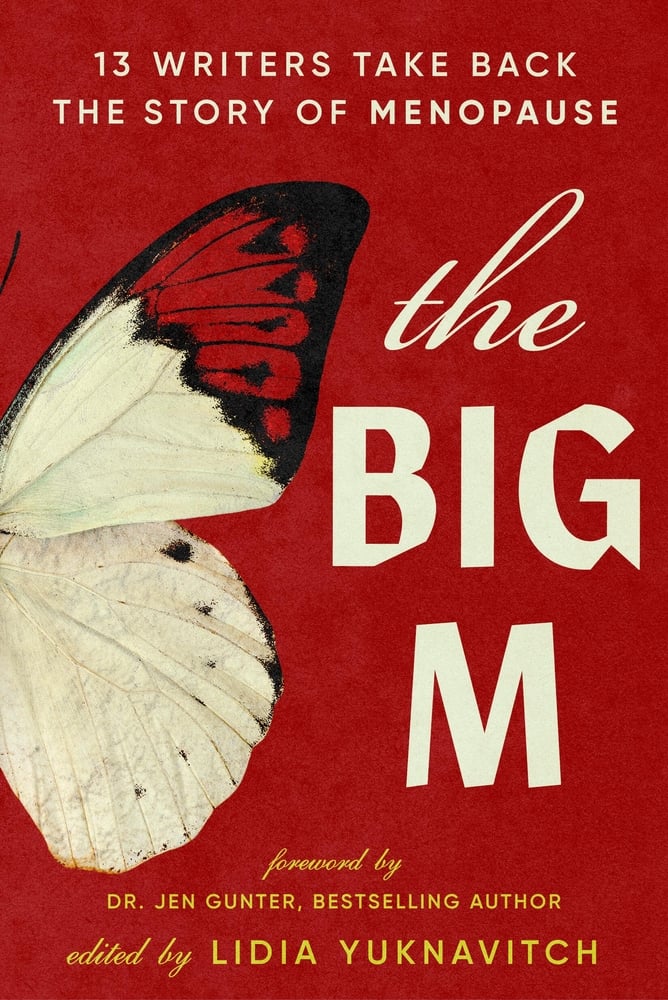

Excerpted from THE BIG M: 13 WRITERS TAKE BACK THE STORY OF MENOPAUSE by Lidia Yuknavitch, copyright ©2026 by Lidia Yuknavitch. Used with permission of Grand Central Publishing, a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven't read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LITEnjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.