The UK’s nuclear decommissioning programme is often seen as a legacy task. For Robin Ibbotson, chief technology officer at Sellafield Ltd, it is also a test bed for innovation – a place where new, often world-first technologies are developed under some of the most demanding safety and regulatory conditions anywhere in industry. Increasingly, ideas proven on the Cumbrian coast are being exported to nuclear programmes overseas.

Ibbotson joined Sellafield four years ago after nearly two decades in the defence sector. There, he learned the complexities of working with government, national security and long–term infrastructure – experiences he describes as “surprisingly transferable” to nuclear. “In both sectors you have one government customer and one mission,” he says. “You’re not just thinking about what a piece of technology can deliver, but what it means for society – for jobs, for skills, for public confidence. It’s about national reputation.”

That sense of responsibility shapes how Sellafield approaches innovation. The site – which covers more than six square-kilometres on the Cumbrian coast – is charged with safely managing nuclear waste and decommissioning redundant facilities as part of the UK’s Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA).

Innovation, Ibbotson says, follows a disciplined logic. “We still go through the same development cycle as any other industry – you test something small–scale, build confidence, and then deploy across a number of nuclear facilities across NDA’s sites,” he explains. “The difference is that we do it under the highest level of scrutiny.”

One of his priorities has been broadening what Sellafield means by “future technology”. Beyond robotics and artificial intelligence, this includes materials science, chemical engineering and digital modelling. “We probably cover the widest technical spectrum of any industry I’ve seen,” he says. “We’re looking at everything from cement and grout – how to keep ageing structures safe – through to advanced robotics that can move into areas where humans can’t.”

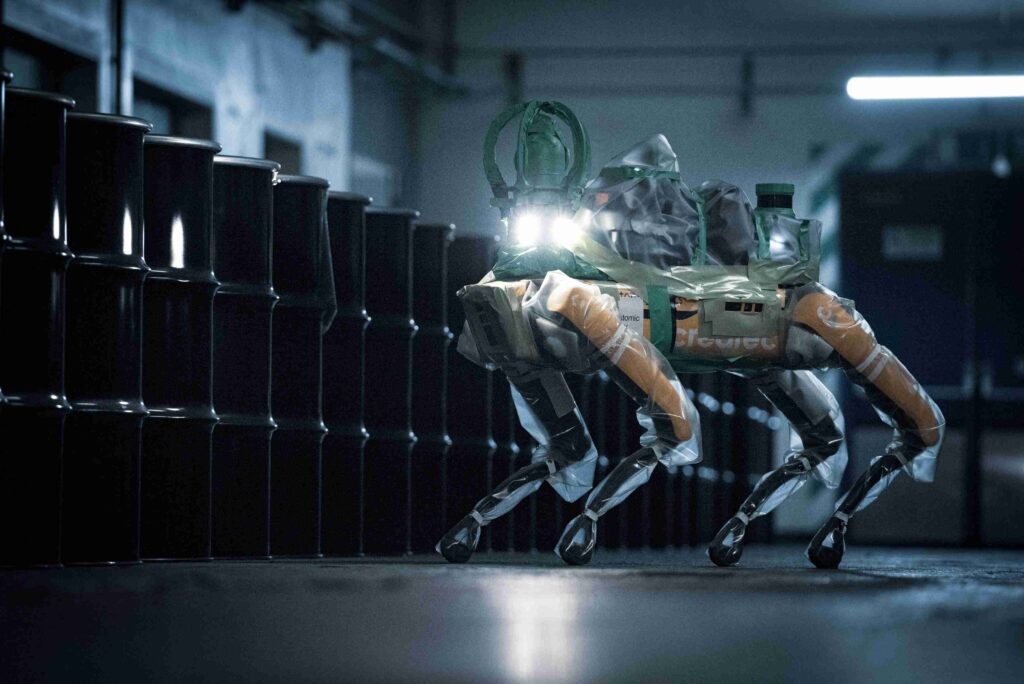

That robotics work has drawn international attention. Using Boston Dynamics’ four–legged robot, Spot, Sellafield engineers have been able to inspect and transport materials inside buildings. “It might take a person hours of preparation to go into a controlled area,” Ibbotson explains. “Spot can do it ten-times faster, because you don’t need to dress it in protective gear or manage exposure. If you break the robot, that’s unfortunate – but it’s not a person.”

Equally significant is the Robotics and Artificial Intelligence Collaboration (RAICo), a partnership between Sellafield Ltd, the NDA, the UK Atomic Energy Authority, Atomic Weapons Establishment and the University of Manchester. The hub, based in Whitehaven, develops early-stage technologies that can later be deployed at Sellafield and across multiple nuclear legacy sites. “We’re a government-owned organisation, so we want to maximise value for taxpayers,” Ibbotson says. “That means sharing what we learn across the sector, not hoarding it.”

Collaboration extends beyond nuclear. Sellafield has worked with the oil and gas and defence industries, and its advances are now being shared internationally. “We’ve shown Canadian labs some of the robotics we’ve developed with local firms in Cumbria, and they’ve pulled that technology through into their own projects,” Ibbotson says. “If we reduce the risk to nuclear globally, it reduces the risk for us too.”

Sellafield has made extensive use of Boston Dynamics’ “Spot” robot. (Credit – Sellafield Ltd)

Sellafield has made extensive use of Boston Dynamics’ “Spot” robot. (Credit – Sellafield Ltd)

Another example of Sellafield’s innovation model is its Game Changers programme, which invites external partners to solve complex technical challenges through small–scale funding calls. “We put out a problem – like detecting hydrogen build–up inside sealed waste containers – and someone from outside our sector might come back with an idea,” Ibbotson says. “We funded one of those concepts to prototype stage, proved it on site, and it’s now being adapted by BP for the hydrogen economy. That’s a win for safety, for innovation and for UK industry.”

At the other end of the spectrum are long–term partnerships, such as Sellafield’s technical services agreement with the UK National Nuclear Laboratory. “Some of the materials we work with can only be handled in one or two facilities in the world,” he notes. “That’s where national labs are essential. They bring the scientific rigour and academic networks that let us push the boundaries safely.”

Beyond the technical achievements, Ibbotson is keenly aware of Sellafield’s wider role in the UK’s innovation landscape – and what makes it an attractive proposition for ambitious scientists. Working at Sellafield, he argues, carries a certain cachet. “If a company can prove a new technology here – in one of the most challenging environments imaginable – it gives them credibility when they go to market elsewhere.”

Looking ahead, he sees the convergence of robotics and AI – what he calls “cobotics” – as the next major step. “It’s about taking the tools to the waste rather than bringing the waste to the tools,” he says. “That changes everything. You can parallelise workstreams, reduce logistics and fundamentally reshape how we decommission.”

The societal implications, he adds, will be significant. “There are always risks with powerful technology, but the nuclear industry is a good place to develop it — because safety and ethics are built into everything we do.”

At Sellafield, quiet progress is often the measure of success. “If we’re doing our job well, the world doesn’t notice,” Ibbotson says. But the technologies being developed on site – in robotics, materials science and automation – are already feeding into other industries, from defence to energy. Much of what is being tested in west Cumbria today will inform how complex infrastructure is managed elsewhere tomorrow.

Treat yourself or a friend this Christmas to a New Statesman subscription for just £2

Related