This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

I still can’t quite wrap my head around how a country built on immigration is now villainizing the very concept. The supposed “melting pot” of America that claimed to welcome the “huddled masses” (which, to be fair, was always a concept contingent on being the “right” kind of immigrant, whatever that meant at a given time) is now locking up anyone deemed not American enough. I’m mad about it, if you couldn’t tell. You should be, too.

If you live in the United States, unless you’re Native American or a descendant of enslaved Black Americans, your however-many-great-grandparents were immigrants, whether fleeing political turmoil, searching for religious freedom, escaping violence, or hoping for better opportunities and a better future. In other words: the very same things that drive people to leave their homelands today in spite of the great risks and cost such undertakings entail. The vast cultural differences in the U.S. are part of what should make this country great. Violence, though an undeniable and unshakeable building block of America’s history, has never and will never make this country great. In fact, violence is America’s most shameful past and present.

Your eyes should be on what’s happening in Minneapolis, an American city currently occupied by thousands of ICE agents, on the deplorable conditions of the concentration camps where children as young as two years old are sickened by unsanitary food and water, on legal permanent residents, green card holders, and asylum seekers the American government has met with hard-hearted hypocrisy and violence, and on the American citizens injured and killed by militarized agents of this regime who continue to act without any investigations or repercussions.

I’m mad, and you should be, too. But a lot of people aren’t. During atrocities throughout history, people are convinced to go along with—or ignore—terrible things when our fellow human beings are scapegoated and dehumanized. Violence that might horrify you if it threatened you or your loved ones can be made to seem palatable if the powers that be convince you it’s only happening to other people, people they’ve made you believe are less-than, are somehow deserving of this violence. Or maybe they just make you believe it’s not happening at all.

But do you know what increases our empathy and ability to understand others? Books. Reading. Fiction. I’m not naive enough to believe reading a few books will be enough to fix the situation we find ourselves in, but I also believe every small ripple we make contributes to the overall trajectory of our future.

Past Tense

Sign up for our weekly newsletter about historical fiction!

Subscribe to Selected No Thanks

These six historical fiction novels about immigrants are each unique facets of the immigrant experience. No two tell the same story. They feature refugees fleeing violence, the children of immigrants searching for belonging, communities both welcoming and hostile, and people, over and over again, trying to figure out what makes a place home. I hope you read them and remember that there is far more that makes us alike than different. I hope you share them or take some time to think about how you could make a difference in your community to protect your neighbors and fellow human beings.

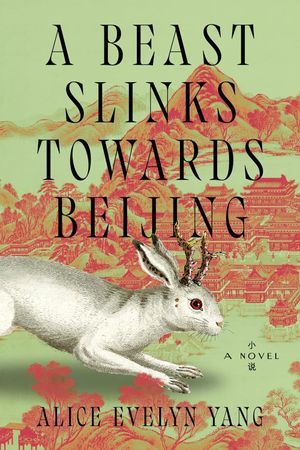

A Beast Slinks Towards Beijing by Alice Evelyn Yang

A Beast Slinks Towards Beijing by Alice Evelyn Yang

Qianze knows very little about her parents’ lives before they came to the U.S. in the wake of China’s Cultural Revolution. But now, the father who abandoned her more than a decade ago has returned, his mind in a state of turbulent dissociation, and begins recounting stories of his horrifying past to explain why he left and why he’s come back. There’s a prophecy left unfulfilled, and whether Qianze wants to hear it or not, her father’s story refuses to remain untold.

America Is Not the Heart by Elaine Castillo

America Is Not the Heart by Elaine Castillo

Newly arrived in America, Hero de Vera hopes she can find a fresh start after being disowned by her parents and seeing firsthand the political violence of the Philippines in the 1980s and ’90s. Her uncle Pol knows not to ask about her past or her injured hands, but her young cousin Roni doesn’t yet understand the pain that might cause someone to flee their homeland for another, much less why they would choose to keep it hidden. Through the lives of three women across generations, Castillo paints a moving portrait of family and the larger-than-life forces that might lead someone to leave one home for another, and why people sometimes make the equally difficult decision to go back.

How Much of These Hills is Gold by C Pam Zhang

How Much of These Hills is Gold by C Pam Zhang

Told in dreamlike transitions of perspective and continuity, C Pam Zhang weaves a heartfelt story of family and belonging in her fabulist novel of the Old West. After the death of their father, two young siblings wander the arid wilderness in search of a path forward and a place to bury his body. But their own experiences are informed by those of their parents years before, and the hopes and harrowing events that brought them to the desert in search of gold.

Kololo Hill by Neema Shah

Kololo Hill by Neema Shah

When an edict demanding all Ugandan Asians leave the country within 90 days, taking only what they can carry and leaving their money behind, never to return, is issued in 1972, a newlywed couple and their family are forced to flee. Asha, Pran, and Jaya leave the growing violence in Kampala for the safety of Britain, not even knowing yet if they’ll be granted refuge.

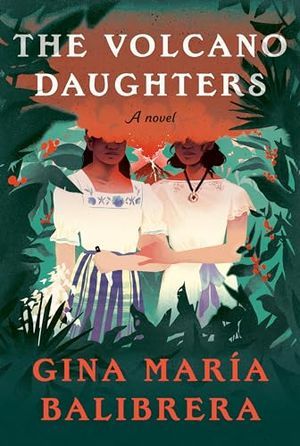

The Volcano Daughters by Gina María Balibrera

The Volcano Daughters by Gina María Balibrera

Focusing on the horrifying experiences that led two young Indigenous Salvadorian sisters to flee their homeland for their lives, The Volcano Daughters is more a story of why people leave than what happens after. When Graciela is taken from the coffee plantation where she lived with her mother to live with her father in the city, she meets the sister she never knew, even as she is forced to leave the rest of her family behind forever. In the capital, Graciela discovers that the country’s dictator, El Gran Pendejo, has an unusual interest in her and her older sister. He believes they’ll help foresee the future. But his attention doesn’t protect them. Far from it; he’s planning a genocide that no one will escape from unscathed.

I Hope You Find What You’re Looking For by Bsrat Mezghebe

I Hope You Find What You’re Looking For by Bsrat Mezghebe

This highly anticipated debut comes recommended from the Well–Read Black Girl Books series, which champions Black literature. I Hope You Find What You’re Looking For explores the lives of three women, recent immigrants to D.C.’s Eritrean community, grappling with what family, nationhood, and peace might look like on the eve of Eritrean independence from Ethiopia.

Want to read more about immigrants or dive into what activism could look like for you? Go forth and read:

Comments (0)