A pair of Sacabambaspis fish, around 35 cm in length, which had distinct, forward-facing eyes and an armored head. No fossils of animals like Sacabambaspis from after the Late Ordovician Mass Extinction event have been discovered. Credit: Nobu Tamura

A pair of Sacabambaspis fish, around 35 cm in length, which had distinct, forward-facing eyes and an armored head. No fossils of animals like Sacabambaspis from after the Late Ordovician Mass Extinction event have been discovered. Credit: Nobu Tamura

One of Earth’s earliest mass extinctions wiped out most ocean life during a sudden global ice age. From the ruins, jawed vertebrates survived, diversified, and transformed the course of evolution.

About 445 million years ago, Earth experienced a sudden and dramatic shift that altered the course of life. In a very short span of geological time, glaciers spread across the supercontinent Gondwana. As ice locked away water, many shallow seas disappeared, transforming the planet into what scientists call an “icehouse climate.” At the same time, ocean chemistry changed in dangerous ways. Together, these forces led to the extinction of roughly 85% of all marine species, which at the time represented most life on Earth.

New research published in Science Advances shows that this devastation also created an unexpected turning point. Scientists from the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST) found that the Late Ordovician Mass Extinction (LOME) ultimately fueled a major rise in vertebrate diversity. During this period of upheaval, one group gained a decisive advantage and set evolution on a new path. That group was jawed vertebrates.

“We have demonstrated that jawed fishes only became dominant because this event happened,” says senior author Professor Lauren Sallan of the Macroevolution Unit at OIST. “And fundamentally, we have nuanced our understanding of evolution by drawing a line between the fossil record, ecology, and biogeography.”

A Promissum conodont, which range from 5 to 50 cm in length and named after unusual, cone-like teeth fossils, and which are hypothesized to be the ancestors of modern lampreys and hagfishes. Very few conodont species survived the Late Ordovician Extinction Event. Credit: Nobu Tamura

Life Before the Late Ordovician Mass Extinction

A Promissum conodont, which range from 5 to 50 cm in length and named after unusual, cone-like teeth fossils, and which are hypothesized to be the ancestors of modern lampreys and hagfishes. Very few conodont species survived the Late Ordovician Extinction Event. Credit: Nobu Tamura

Life Before the Late Ordovician Mass Extinction

The Ordovician period, which lasted from about 486 to 443 million years ago, was a very different chapter in Earth’s history. Gondwana dominated the southern half of the planet and was surrounded by warm, shallow seas. Ice had not yet formed at the poles, and greenhouse conditions kept ocean waters mild. Along coastlines, early plant life resembling liverworts began to appear, accompanied by many-legged arthropods.

Marine ecosystems were far more developed. The oceans were filled with unusual and diverse creatures. Lamprey-like conodonts with large eyes moved through forests of giant sea sponges. Trilobites crawled along the seafloor among dense groups of shelled mollusks. Enormous sea scorpions and massive nautiloids with pointed shells reaching up to five meters hunted in open water. Early ancestors of gnathostomes, or jawed vertebrates, existed at this time but were rare and easily overlooked among the dominant marine animals.

Two Phases of a Planetary CrisisScientists still debate the exact cause of LOME, but the fossil record clearly shows that life before and after the event looked very different. “While we don’t know the ultimate causes of LOME, we do know that there was a clear before and after the event. The fossil record shows it,” says Prof. Sallan.

The extinction unfolded in two major stages. First, Earth shifted rapidly from a greenhouse climate to an icehouse climate. Glaciers spread across Gondwana and shallow marine habitats dried up. Several million years later, just as ecosystems began to rebound, the climate shifted again. Ice melted, sea levels rose, and warm waters flooded the oceans. These waters were low in oxygen and rich in sulfur, overwhelming species that had adapted to colder conditions.

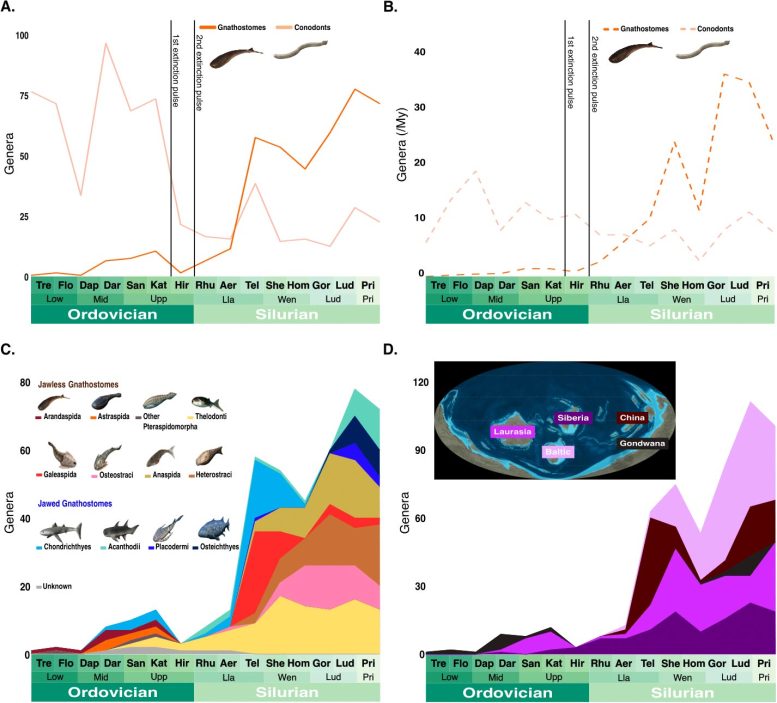

The fall in jawless vertebrates coincides with the rise of jawed vertebrates following the two pulses of the Late Ordovician Mass Extinction (LOME). Top genus-level diversity curves follow global, taxonomic richness in genera – i.e. the number of identified genera – per geological stage (A.) and per million years in each stage (B.). Notice the sharp change during the final stage of the Ordovician period, the Hirnantian (Hir).

The fall in jawless vertebrates coincides with the rise of jawed vertebrates following the two pulses of the Late Ordovician Mass Extinction (LOME). Top genus-level diversity curves follow global, taxonomic richness in genera – i.e. the number of identified genera – per geological stage (A.) and per million years in each stage (B.). Notice the sharp change during the final stage of the Ordovician period, the Hirnantian (Hir).As these waves of extinction swept through the oceans, many vertebrate survivors were pushed into refugia. These were isolated regions of biodiversity cut off by deep ocean barriers that few species could cross. Within these confined environments, jawed vertebrates appear to have had a distinct advantage.

To investigate this pattern, the research team assembled a new fossil database drawing on more than 200 years of late Ordovician and early Silurian paleontological research. “We pulled together 200 years of late Ordovician and early Silurian paleontology,” says first author Wahei Hagiwara, a former research intern in the Macroevolution Unit who is now an OIST PhD student. The database allowed the scientists to reconstruct ecosystems within the refugia and measure changes in genus-level diversity. Their results show that LOME was followed by a slow but striking rise in gnathostome diversity. “And the trend is clear – the mass extinction pulses led directly to increased speciation after several millions of years.”

Geography Shapes Evolutionary OpportunityBy analyzing fossil evidence from around the world, the researchers were able to link rising jawed vertebrate diversity not only to extinction but also to location. “This is the first time that we’ve been able to quantitatively examine the biogeography before and after a mass extinction event,” says Prof. Sallan. Tracking species movements across the globe allowed the team to identify specific refugia that later fueled vertebrate diversification.

One key region was what is now South China. Fossils from this area include the earliest complete remains of jawed fishes closely related to modern sharks. According to Hagiwara, these animals remained in stable refuges for millions of years. Only after developing the ability to cross open oceans did they spread into other marine environments.

How New Niches Drove InnovationThe study also addresses a long-standing question in evolutionary biology. “Did jaws evolve in order to create a new ecological niche, or did our ancestors fill an existing niche first, and then diversify?” asks Prof. Sallan. “Our study points to the latter.”

As jawed vertebrates became confined to small geographic areas, they encountered ecosystems with many available roles left behind by extinct jawless species and other animals. This abundance of open niches allowed them to diversify rapidly. A similar process can be seen in Darwin’s finches on the Galápagos Islands, where access to new food sources led to dietary specialization and gradual changes in beak shape.

An Ecological Reset, Not a Clean SlateWhile jawed fishes remained restricted to South China, jawless vertebrates continued to thrive elsewhere and dominated open oceans for another 40 million years. These groups diversified into many reef-dwelling forms, some with alternative mouth structures. Why jawed vertebrates eventually overtook them after spreading beyond the refugia remains unclear.

What the researchers did uncover is that LOME did not erase ecosystems entirely. Instead, it triggered what they describe as an ecological reset. Early vertebrates moved into roles once filled by conodonts and arthropods, rebuilding familiar ecosystem structures using different species. Similar patterns appear repeatedly throughout the Paleozoic era after extinction events driven by comparable environmental changes. The team refers to this repeating process as a “diversity-reset cycle,” where evolution restores ecosystems by converging on similar functional designs.

Why Ancient Survivors Still Matter TodayProf. Sallan summarizes the significance of the findings. “By integrating location, morphology, ecology, and biodiversity, we can finally see how early vertebrate ecosystems rebuilt themselves after major environmental disruptions. This work helps explain why jaws evolved, why jawed vertebrates ultimately prevailed, and why modern marine life traces back to these survivors rather than to earlier forms like conodonts and trilobites. Revealing these long-term patterns and their underlying processes is one of the exciting aspects of evolutionary biology.”

Reference: “Mass extinction triggered the early radiations of jawed vertebrates and their jawless relatives (gnathostomes)” by Wahei Hagiwara and Lauren Sallan, 9 January 2026, Science Advances.

DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aeb2297

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.