Physicists have uncovered hidden magnetic patterns lurking inside a puzzling state of matter called the pseudogap, which appears just before certain materials become superconductors. Credit: Shutterstock

Physicists have uncovered hidden magnetic patterns lurking inside a puzzling state of matter called the pseudogap, which appears just before certain materials become superconductors. Credit: Shutterstock

Scientists have uncovered hidden magnetic order inside the pseudogap, bringing us closer to engineering high-temperature superconductors.

Physicists have identified a connection between magnetism and an unusual state of matter known as the pseudogap. This phase appears in some quantum materials at temperatures just above where they become superconductors. The discovery may help scientists design new materials with valuable properties, including high-temperature superconductivity, where electrical current moves with no resistance.

To uncover this link, researchers used a quantum simulator cooled to temperatures barely above absolute zero. They observed a consistent pattern in how electrons affect the magnetic orientation of nearby electrons as the system cools. Since electrons can have spin up or down, these interactions shape the material’s magnetic behavior. The work marks an important advance in understanding unconventional superconductivity and involved close collaboration between experimental physicists at the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics in Germany and theorists, including Antoine Georges, director of the Center for Computational Quantum Physics (CCQ) at the Simons Foundation’s Flatiron Institute in New York City.

The team published its findings during the week of January 19 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

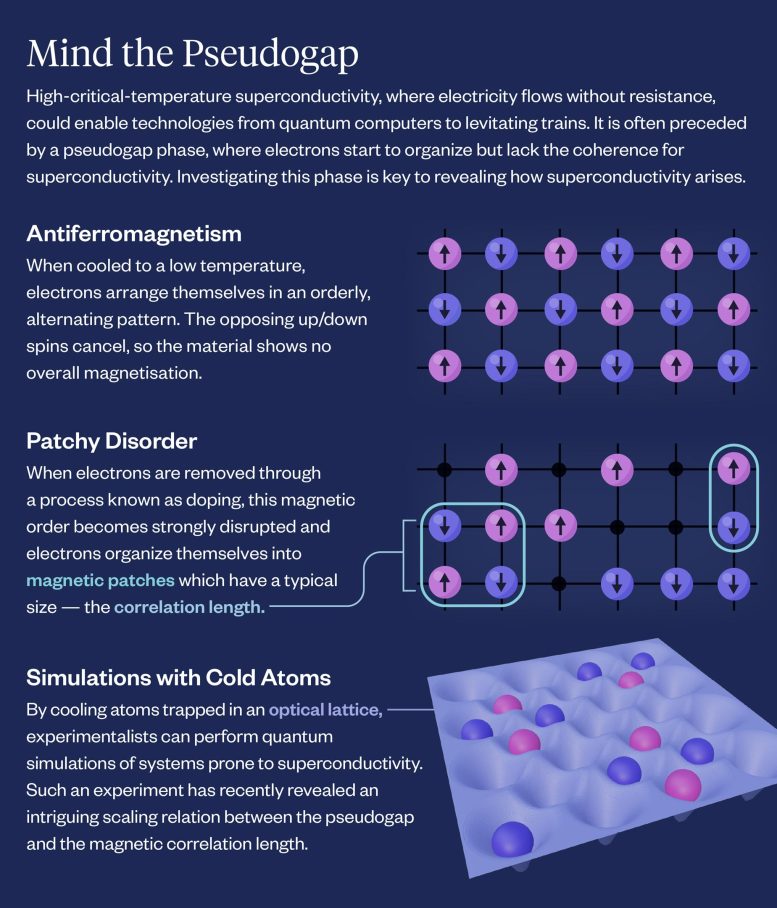

An infographic illustrating the pseudogap. Credit: Lucy Reading-Ikkanda/Simons Foundation

Why the Pseudogap Matters

An infographic illustrating the pseudogap. Credit: Lucy Reading-Ikkanda/Simons Foundation

Why the Pseudogap Matters

Superconductivity has been studied for decades because of its potential to transform technologies ranging from power grids to quantum computers. Despite that effort, scientists still do not fully understand how superconductivity arises, especially in materials that operate at relatively high temperatures.

In many high-temperature superconductors, the superconducting phase does not emerge directly from a typical metallic state. Instead, the material first enters the pseudogap phase. During this stage, electrons behave in unexpected ways, and the number of available states for electrical flow decreases. Researchers widely believe that understanding the pseudogap is essential for explaining how superconductivity forms and for developing materials with better performance.

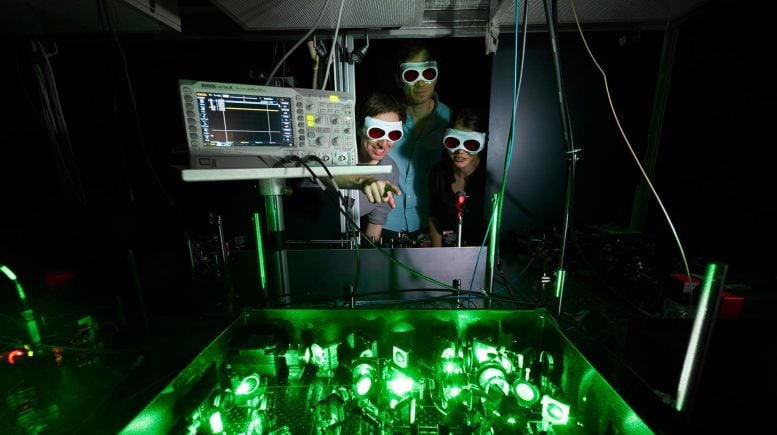

Researchers look at the quantum simulator setup used to investigate the pseudogap. Credit: Max Planck Institute of Quantum Physics

Magnetism Under Disruption

Researchers look at the quantum simulator setup used to investigate the pseudogap. Credit: Max Planck Institute of Quantum Physics

Magnetism Under Disruption

When a material contains the usual number of electrons, those electrons tend to form a neat magnetic arrangement called antiferromagnetism. In this pattern, neighboring electron spins point in opposite directions, similar to a perfectly coordinated left right sequence.

That order is disrupted when electrons are removed through a process called doping. For many years, scientists assumed that doping completely eliminated long-range magnetic order. The new PNAS study challenges that assumption. At extremely low temperatures, the researchers found that a subtle form of organization persists, even though the system appears disordered. This experimental work was guided by earlier theoretical research on the pseudogap carried out at the CCQ, which led to a 2024 paper in Science.

From Chaos to Universal OrderTo explore these effects, the team relied on the Fermi-Hubbard model, a widely used theoretical description of how electrons interact inside solids. Instead of studying real materials, the researchers recreated the model using lithium atoms cooled to billionths of a degree above absolute zero. These atoms were held in a precisely controlled optical lattice formed by laser light.

Ultracold atom quantum simulators allow scientists to reproduce complex material behavior under conditions that cannot be achieved in conventional solid-state experiments. Using a quantum gas microscope, which can image individual atoms and detect their magnetic orientation, the team collected more than 35,000 detailed images. These snapshots captured both atomic positions and magnetic correlations across many temperatures and doping levels.

“It is remarkable that quantum analog simulators based on ultracold atoms can now be cooled down to temperatures where intricate quantum collective phenomena show up,” says Georges.

A Universal Magnetic SignatureThe researchers observed a striking result. “Magnetic correlations follow a single universal pattern when plotted against a specific temperature scale,” explains lead author Thomas Chalopin of the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics. “And this scale is comparable to the pseudogap temperature, the point at which the pseudogap emerges.” This finding shows that the pseudogap is closely tied to subtle magnetic structures hidden beneath what looks like randomness.

The study also revealed that electrons in this regime interact in more complex ways than previously thought. Rather than forming simple pairs, they organize into larger, multiparticle correlated groups. The presence of even one dopant can disturb magnetic order across a surprisingly wide region. Unlike earlier experiments that measured interactions between two electrons at a time, this work captured correlations involving up to five particles simultaneously, a level of detail reached by only a few laboratories worldwide.

Revealing Hidden CorrelationsFor theorists, the results offer a new standard for testing models of the pseudogap. More broadly, the findings move scientists closer to understanding how high-temperature superconductivity arises from the collective motion of interacting, dancing electrons. “By revealing the hidden magnetic order in the pseudogap, we are uncovering one of the mechanisms that may ultimately be related to superconductivity,” Chalopin explains.

The research also underscores the value of tight coordination between theory and experiment. By pairing detailed predictions with carefully controlled quantum simulations, the team was able to uncover patterns that would otherwise remain invisible.

This international collaboration combined experimental precision with theoretical insight. Future experiments aim to cool the system even further, search for additional forms of order, and develop new ways to observe quantum matter from fresh perspectives.

“Analog quantum simulations are entering a new and exciting stage, which challenges the classical algorithms that we develop at CCQ,” says Georges. “At the same time, those experiments require guidance from theory and classical simulations. Collaboration between theorists and experimentalists is more important than ever.”

Reference: “Observation of emergent scaling of spin–charge correlations at the onset of the pseudogap” 19 January 2026, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2525539123

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.