In 1844, Britain compelled the Qing government to ship nine and a half tonnes of silver from southeast China to London as ransom after the First Opium War. It was melted down at the Royal Mint: bullion extracted at gunpoint from a civilisation forced open to British drugs and capital. That war marked the beginning of China’s “century of humiliation.”

Nearly 200 years on, the same site – Royal Mint Court – is set to house China’s largest embassy in Europe. Between those two moments lies one of history’s great reversals. China passed through imperial dismemberment, fascist occupation, civil war and socialist revolution to become the world’s central industrial power. Britain passed from empire to offshore clearing house, from workshop to rentier economy, from rule-maker to rule-taker – a transformation that enriched a narrow stratum while hollowing out the country beneath it.

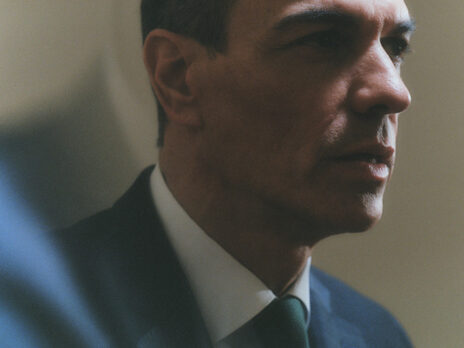

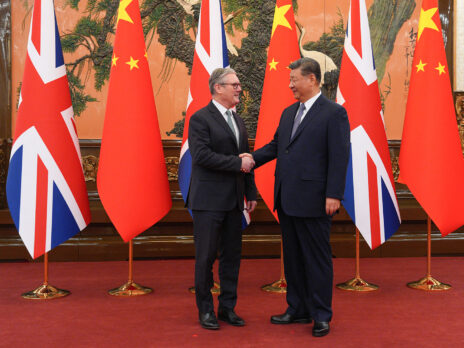

Keir Starmer’s visit to Beijing, which concluded today (31 January), belongs to this history. It is the first trip by a British prime minister in eight years, and it brought him into formal talks with President Xi Jinping in the Great Hall of the People, alongside meetings with ministers and business leaders aimed, in his words, at a “more sophisticated relationship”. He arrived in a capital whose ancient heart now sits inside a vastly expanded modern state, where ring roads stretch to the horizon, high-speed rail threads the city, and ministries operate at a scale unmatched in Europe. But on an even grander scale, it marked the meeting between a civilisational state that now shapes the world economy and a country still searching for a role after its hegemony came to an end.

Economic gravity is pulling the world towards China. The question is whether Britain’s governing class can abandon the consolations of Cold War fantasy long enough to negotiate with reality. For decades, British foreign policy rested on a simple settlement: economic integration with Europe, strategic subordination to the United States. Brexit severed the European pillar. Now the American one is shifting too. Under Trump, Washington treats allies as dependants, law as optional, and security as a bargaining chip. The pretence of a rule-bound order has given way to something cruder.

New year, new read. Save 40% off an annual subscription this January.

In this environment, the language of “Cold War 2.0”, of civilisational contest with modern China, flatters British elites into thinking they still belong to a coherent Western bloc. It substitutes moral drama for material strategy, and invites a posture of self-harm: treating the world’s manufacturing centre as a moral hazard, while continuing to import its products without leverage. Even modest departures from this script have been met with pressure. Britain’s decision to exclude Huawei from 5G infrastructure – taken at Washington’s insistence – showed how narrow the space for independent judgment had already become.

Starmer should be wary, too, of repeating David Cameron’s Chinese charm offensive. In practice it meant little more than inviting Chinese capital into British assets in order to juice the City. It was engagement without production, partnership without construction. Early signals from Starmer’s trip point in a similar direction: an emphasis on services over industry, with positive but marginal gains – such as visa-free travel – standing in for anything structurally transformative.

Britain’s problem is not that it speaks too softly to Beijing. It is that it no longer builds. It cannot complete major rail projects without years of chaos. It allows its energy system to be shaped by market failure and foreign dependence. It talks the language of partnership while behaving as a vassal – deferring its economic horizons, technological standards and strategic priorities to Washington. A new relationship with China is a necessity born of a moment of global transition – a world shaped by climate catastrophe, resurgent imperialism and deepening geopolitical rivalry.

China has fused state coordination, public enterprise, strategic finance and market discipline into an industrial machine of unprecedented scale. The results are staggering. In two generations it has overseen the fastest expansion of productive capacity in human history. Entire industrial ecosystems have been built from scratch. Around 800 million people have been lifted out of poverty as real incomes have risen 25-fold.

The change is written on bodies as well as balance sheets. In the mid-1980s, five-year-old Chinese girls were, on average, seven centimetres shorter than their US American counterparts; by 2019 they were two taller. The average height of young Chinese men has risen by several inches in a single generation. It is little wonder that surveys conducted by Harvard’s Ash Centre found more than 90 per cent expressing satisfaction with their government.

This legitimacy rests on material achievement. In energy, infrastructure and manufacturing, China now operates on a scale unmatched elsewhere. The energy transition makes this impossible to ignore. China is central to the supply chains of decarbonisation: from solar manufacturing to batteries to grid components. In 2024, China invested more than $625bn into clean energy and hit its wind-and-solar capacity target six years early. Over half the world’s solar energy capacity is installed in China and it is responsible for four fifths of world exports of solar panels.

China is also the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter – a consequence of becoming the workshop of a carbon-intensive global economy. But that is precisely why its trajectory matters. The same state capacity that powered its industrial ascent is now being deployed to rewire it. China’s emissions have begun to fall; per-capita output has only just reached around 60 per cent of the United States’, while American emissions continue to rise. Today, Chinese industry is both a driver of the climate crisis and the central engine of its solution. China shows that decarbonisation requires a material revolution: grids, ports, rail, batteries, heat pumps, high-grade steel, concrete, semiconductor capacity and the strategic planning, patient capital and enterprise management that binds these elements into functioning systems.

Britain already has a foothold in this future. It is a global leader in offshore wind. But leadership in deployment is not yet leadership in production. Much of the value in turbines and critical components remains concentrated in China, especially in generators, castings and rare-earth inputs. A better relationship with Beijing would include technological cooperation and joint ventures that anchor more of that production at home – with the jobs, skills and durable industrial base that entails.

Steel exposes what is at stake. The green transition is steel-hungry by definition: turbines, pylons, rail and grids will all be built from it. Yet Britain’s capacity to make primary steel nearly vanished in 2025, when the government had to rush through emergency legislation to prevent the Scunthorpe blast furnaces from being switched off by their private Chinese owner. Steel must be treated as infrastructure – anchored by public direction rather than left to owners whose horizons are short and commitments are thin.

This points toward deeper questions about the British economy. A successful economy does three things: increases real wages, improves and expands public services, and builds productive and technological capacities. Britain’s economic model, dominated by finance, asset-price inflation, and shareholder returns, has manifestly failed on these tests. China’s model – imperfect and not to be copied wholesale – has delivered remarkable structural transformation at scale. We should neither romanticise it nor dismiss what can be learned from it: strategic planning, public ownership in key sectors, socialised finance directed toward production rather than speculation, and guardrails to prevent capital from dominating the state.

You cannot build a green economy while pretending the world’s manufacturing centre does not exist. China’s centrality to the green transition makes engagement unavoidable. The US response has been to carve the world into competing economic zones: to restrict technology flows, weaponise tariffs, and press allies into an economic cordon sanitaire.

The real alternative is not a change of patron, but a change of order. Britain should be working with others to help build a world in which power is constrained by rules rather than exercised through raw coercion – where trade, technology and security are governed by reciprocity, not domination. That means resisting a return to great-power partition, and instead contributing to a genuinely multilateral settlement in which states deal with one another with mutual respect.

That does not mean exchanging one dependency for another. It also entails deepening relations with the European Union on strategic autonomy and trade; building partnerships with rising powers like Brazil, Mexico, Malaysia and South Africa; and supporting other “middle powers”, in Mark Carney’s words, to break free from US domination. Our posture should be global in scope and practical in aim. Much of Britain’s contemporary right instead points in the opposite direction, including the “radical” Reform UK. It promises control while binding the country more tightly to Washington’s strategic orbit.

A new relationship with China should be judged by what it builds. Britain does not need more capital sloshing into asset bubbles. It needs productive capacity. It does not want Chinese money to replace BlackRock as landlord of decaying infrastructure. It wants technology and skills transfer, joint ventures, co-investment in green manufacturing, and patient finance directed at the real economy: grids, rail, green steel, ports, batteries.

Such a relationship does not mean ignoring human rights in China. It means taking them seriously everywhere. The world in which Britain lectured others on liberty was built on gunboats, famines, partitions and empires. Today the Western order enforces its will through wars of choice, coups and sanctions that devastate whole societies. A 2025 Lancet Global Health study estimates that US and European unilateral sanctions are associated with around 500,000 deaths a year, and some 38 million since 1970.

Britain’s concern for rights in Xinjiang or Hong Kong will only be heard if it is voiced without imperial posture or double standards. A country that trades freely with Saudi Arabia, arms Israel, and defers to the United States on war and sanctions cannot expect its lectures to be received as disinterested principle. Human rights function when they are applied as universal protections, not as an instrument of hierarchy.

One fact deserves saying plainly: China’s external posture is more predictable and peaceful than Washington’s. Beijing can be hard-nosed. But it tends to think in long arcs and to prefer stable arrangements that facilitate trade and investment. The United States, with over 800 military bases around the world, has bombed at least seven countries in the last 12 months while erratically deploying tariffs as a tool of coercion. Britain must ask what kind of world it is preparing itself to inhabit.

The silver from Guangzhou once arrived at the Royal Mint as tribute extracted by force. The new Chinese embassy will arrive by planning consent and purchase order. If the British ruling class cannot tell the difference, it will continue to drift: denouncing the future while importing it, clinging to a collapsing order while failing to build a new one.

A new, sensible relationship with China would be a declaration that Britain intends to stop drifting. The ruling class clings to imperial reflexes because it has no material project for renewal – and breaking with those reflexes is inseparable from creating one. A country that no longer builds and whose elite lives off rents becomes a non-playing character in other people’s stories. To change course means rebuilding at home and rethinking how we stand abroad.

A pragmatic relationship with China is one step in that turn: away from managed decline, towards an economy that works for the many not the few; away from US obedience, towards an international order shaped by rules rather than coercion. It is not a guarantee of renewal. But without it, renewal is scarcely imaginable.

[Further reading: We are living through regime change]

Content from our partnersRelated

Comments (0)