Once you discover a feature that makes your work easier, cleaner, smarter, and more professional, it’s natural to want to use it everywhere. Excel tables often fall into this category. They look structured, behave intelligently, and promise to keep chaos at bay, especially when your spreadsheet starts to grow beyond a handful of rows and columns.

However, just because a feature is powerful does not mean it belongs in every situation. I’ve learned that creating tables, all the time, in Excel can actually introduce more friction than clarity. So, before defaulting to tables in your next worksheet, it’s worth understanding where they can get in the way.

When your data isn't really tabular For layouts that behave more like databases

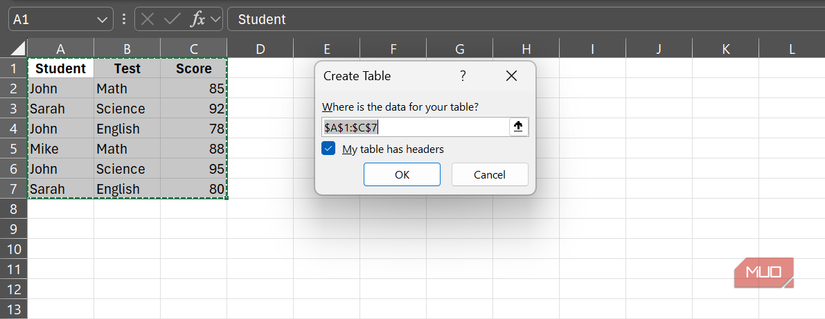

Not everything in a spreadsheet deserves to live inside a table, even when the information is neatly arranged in rows and columns. When you work with pivoted or summarized data, such as monthly totals by department or account, you’re no longer dealing with raw records. You’re presenting conclusions. These summaries usually need breathing room, custom formatting, and descriptive labels that help tell a story, and those needs often clash with the rigid structure that tables impose.

Excel tables are designed for data at its most granular level, where each row represents a single record, and each column represents a single field. Once you move beyond that structure, tables start to feel more restrictive than helpful.

The same problem shows up with constants and what-if variables in Excel. Percentage rates used for scenario modeling are reference values, not datasets, and they belong in clearly labeled cells where they are easy to find and adjust. Forcing them into a table adds unnecessary complexity and blurs the line between your underlying data and the tools you are using to analyze it.

Related

These 3 Excel functions make me feel like a spreadsheet wizard

Related

These 3 Excel functions make me feel like a spreadsheet wizard

Spreadsheets don’t have to be boring when formulas do the heavy lifting.

By keeping assumptions and reference values outside of tables, I find that my spreadsheet logic stays clearer, my layouts remain more flexible, and the workbook itself becomes much easier to understand and maintain.

Performance drain and file size headaches Tables can slow you down instead of making you faster Screenshot by Ada

Screenshot by Ada

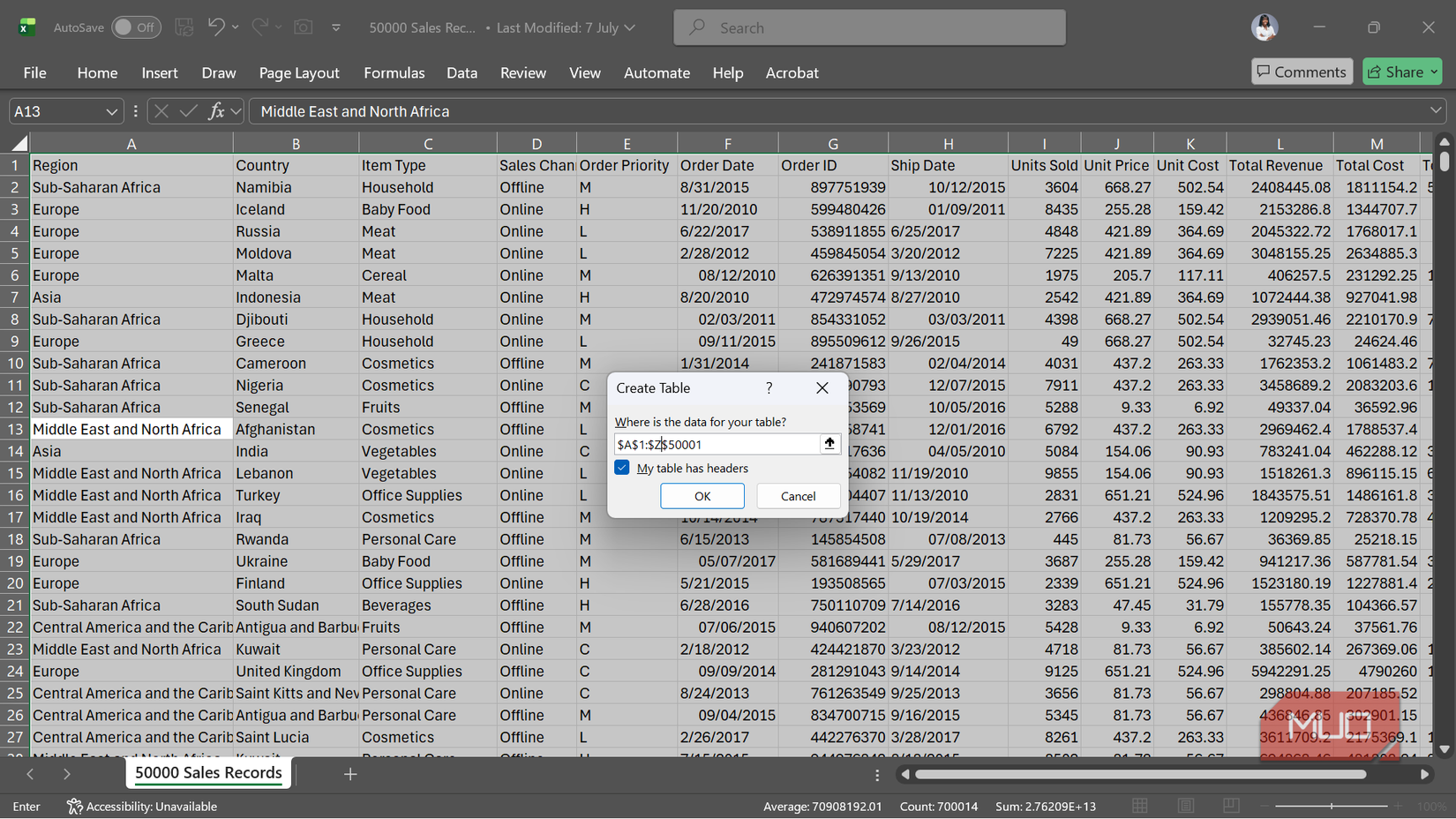

Excel tables can slow a workbook down, especially once you start working with large datasets. I’ve seen noticeable performance drops when managing tables with thousands of rows, and in some cases, converting tables back into regular ranges can reduce file sizes by 20–30%.

The performance hit becomes even more pronounced when pivot tables in your Excel workbook reference these large tables. Tables are designed to auto-expand as new data is added, which sounds convenient but often leads to constant recalculation behind the scenes. As data flows in, formulas refresh more frequently than necessary, and the workbook can start to feel sluggish.

With smaller datasets, sluggishness is rarely a problem. However, when you’re dealing with substantial volumes of information, the trade-off is harder to justify. In those situations, I often find that a well-structured range with intentional, manual expansion delivers better performance.

Screenshot by Ada

Screenshot by Ada

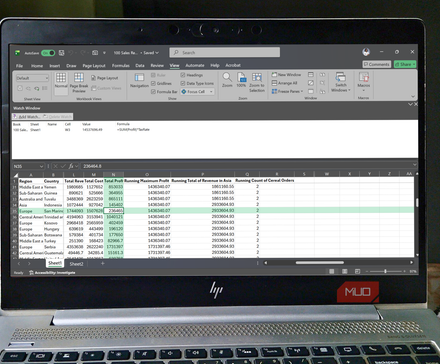

Some of Excel’s most powerful modern features simply do not work inside tables. Dynamic array formulas, often called spill formulas, break the table model because their results are not confined to a single cell. Functions like UNIQUE, FILTER, HSTACK, and VSTACK are designed to expand dynamically, which means they cannot live inside a table at all.

As a result, you either use tables for their organizational structure or you use modern formulas for their analytical power, but you cannot combine the two.

Formula conflicts are not the only issue. Tables also disable or complicate features like Custom Views and the Subtotals command. Even seemingly helpful behaviors, such as automatic formula filling, can become an issue when you need different formulas in different rows of the same column and end up fighting Excel’s insistence on consistency.

Related

When you rely on specific cell references

Structured references aren't always the clarity boost you expect

Related

When you rely on specific cell references

Structured references aren't always the clarity boost you expect

Screenshot by Ada

Screenshot by Ada

If a part of your workflow requires a value to stay in a specific location, such as a total that must always sit in cell B5, Excel tables can actually get in the way.

In a standard range, a formula like this behaves like a GPS coordinate:

=$B$5It doesn’t care what the data represents; it simply points to a location and retrieves the value from that exact spot. Tables, on the other hand, rely on structured references such as Table1[@Total], which forces you to think in terms of column names and row context instead of value placement. When all you want is to reference a single cell, this added step just makes your formulas longer and harder to work with than they need to be.

Structured references also become difficult to read once formulas grow more complex. Referring to a column as Transactions[Date] instead of A2:A2138 sounds cleaner when it’s the only reference in a formula. However, it’ll become increasingly confusing with each additional reference nested inside a single formula. These issues are rarely deal-breakers in simple worksheets, but they tend to compound as models become more sophisticated, adding friction where none is needed.

Related

Excel tables are powerful, but only when the structure fits

Related

Excel tables are powerful, but only when the structure fits

None of this means Excel tables are a bad idea. When your data is transactional, continuously growing, and meant for analysis, tables are often irreplaceable. In those situations, they bring order, consistency, and efficiency to a workbook. However, when your data does not fit that mold, tables can feel restrictive, slow, or a little too clever for their own good.

I always try to remember that Excel tables are not a one-size-fits-all solution, and that’s the whole point. So, before you convert your next range into a table, it’s worth asking whether your actual needs align with what tables are designed to do, or whether a simpler structure would serve you better.