Understanding the role of the gut-hormone axis in women’s health could open untapped opportunities for addressing complex conditions and significant life events including fertility, postpartum recovery and menopause writes Holly Neill

Females have historically been underrepresented in scientific research which has contributed to gaps in our understanding of female health, ranging from pharmacokinetics to symptom presentation. However, there is now growing recognition of the need for sex-specific research, particularly in areas such as the gut microbiome. From monthly hormonal cycles to major life transitions like pregnancy and menopause, women’s bodies undergo continuous physiological change – and the gastrointestinal system is particularly sensitive to these fluctuations.

Beyond the Belly

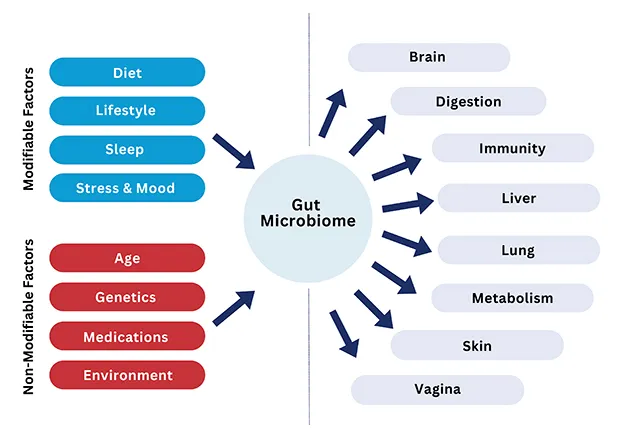

Previously, the role of the gut microbiome was thought to relate solely to digestion, yet research continues to reveal that its influence extends far beyond – including immunity, brain function, skin health, hormones and much more (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The gut microbiome is impacted by many modifiable and non-modifiable factors, and subsequently influences multiple organs and systems

The Gut-Hormone Connection

The relationship between the gut microbiome and sex hormones, known as the gut-hormone axis, is bidirectional and complex. Oestrogen and progesterone receptors are expressed in intestinal epithelial cells and immune cells, meaning sex hormones directly modulate gut physiology, while in turn the gut microbiome can regulate circulating hormone levels. At Yakult, we conducted a survey of over 2,000 female adults and found that, while 91 per cent of women recognise the importance of gut health, only one in 10 have heard of the gut-hormone axis.

At the centre of this gut-hormone relationship lies the oestrobolome – a subset of gut microbes capable of metabolising oestrogens. After circulating through the body, oestrogen is inactivated in the liver and excreted into the gut via bile. However, certain microbes within the oestrobolome produce the enzyme β-glucuronidase, which can deconjugate these oestrogens, allowing them to be reabsorbed into the bloodstream rather than excreted.1

This recycling process modulates the levels of active oestrogen in the body, and is largely dependent on the composition and activity of the gut microbiota – particularly bacteria from the Bacteroides and Firmicutes phyla.2 Disruptions in microbial balance, including reduced diversity or overgrowth of β-glucuronidase-producing bacteria, may therefore impact oestrogen levels and related physiological processes.

Given oestrogen’s systemic role – influencing weight regulation, libido, mood, bone, brain, immune, and cardiovascular health – the oestrobolome represents a critical, and often overlooked, mechanism in women’s health. A balanced gut microbiome will enable optimal oestrogen recycling whilst an imbalance, referred to as ‘dysbiosis’, can lead to excess or deficient oestrogen levels which may increase risk of endometriosis, fibroids and menopausal symptoms.

Menstrual Cycle

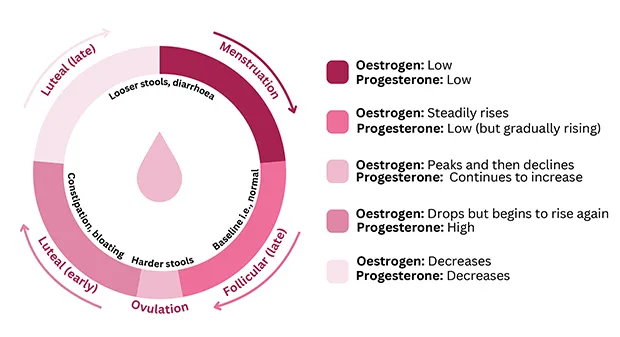

The gut microbiome and menstrual cycle are closely interconnected, influencing each other through hormonal and physiological pathways. Fluctuating levels of hormones, specifically oestrogen and progesterone, can be responsible for cyclical changes to gastrointestinal function and symptoms throughout the menstrual cycle as both affect gastric motility and gut permeability via these receptors present in the gut (see Figure 2).3

These shifts can alter metabolic pathways, including bile acid metabolism, serotonin synthesis and immune activation, which contribute to menstrual-related mood and pain symptoms. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiome can amplify period symptoms and heighten pain sensitivity, potentially causing additional premenstrual syndrome (PMS) symptoms, digestive symptoms, inflammation and cramping. However, more research is needed to clarify causality and mechanisms.

Figure 2: Changes during menstrual cycle (from Yakult Science for Health resource, ‘The Female Gut Health Guide’)

Fertility

A handful of studies have suggested that gut dysbiosis in both females and males could be linked to infertility, reduced implantation rates, miscarriage, preterm birth, pre-eclampsia, and endometriosis. For instance, pre-clinical and observational studies have provided evidence of a correlation between alterations in gut microbiota composition and infertility.4-5

While concrete proof supporting the causal relationship is still lacking, emerging research, particularly regarding male infertility, shows promise. In females, it has been suggested that dysbiosis of the gut could potentially lead to vaginal and uterine dysbiosis which negatively affects endometrial receptivity at the time of implantation.6

The gut microbiota has also been implicated in conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and endometriosis which are risk factors for infertility. Lower gut microbiota diversity and dysbiosis are common features of PCOS7 and endometriosis,8 which may impact disease onset and progression.

Postpartum Depression

Postpartum depression (PPD) is one of the common complications of childbirth, occurring in 10–15 per cent of women. Differences in gut microbiota and microbial-derived metabolites (i.e., short-chain fatty acids) are evident between women with PPD and those without PPD.9

This has been associated with the disruption of multiple signalling pathways and systems that ultimately lead to PPD development.9 Targeting the gut-brain axis through diet and lifestyle interventions, including psychobiotics (live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, can confer mental health benefits), may open underexplored opportunities to support the prevention or symptom management of PPD.

Menopause

As women age, gut microbiota diversity tends to decline, and becomes more similar to males.10 Postmenopausal women have lower gut microbiome diversity and altered overall composition compared to premenopausal women as well as a decreased abundance of gut microbial β-glucuronidase, the enzyme involved with oestrobolome. Specifically, there is a decrease in the Firmicutes:Bacteroidetes ratio after menopause. There is a greater abundance of Butyricimonas, Dorea, Prevotella, Sutterella and Bacteroides, and lower number of Firmicutes and Ruminococcus in postmenopausal women.

However, more research is needed to fully understand the specific functions and health implications of these bacterial changes.10 Research suggests HRT may reduce gut microbiota dysbiosis.11 As women are at a higher risk of developing cognitive conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease and dementia compared to men, there is also a need to understand the sex-specific role of the gut-brain axis in healthy vs declining cognition.

Practical Guidance for Patients

A balanced gut microbiome underpins nearly all aspects of women’s health including hormone regulation, mood and cognition, immunity, inflammation, metabolism and reproductive health. Ensuring gut microbial stability through diet, exercise, sleep and stress management can support the gut-hormone axis.

Encourage patients to make one gut-related change at a time whilst reinforcing self-compassion and flexibility. Considering diet, emphasise the importance of consuming fibre (e.g. fruit, vegetables, wholegrains, beans, lentils) and polyphenols (e.g. berries, olive oil, dark chocolate) with a focus on inclusion rather than exclusion. Encourage aiming for 30 different plant foods across a week to promote diversity, as well as including fermented foods. Discuss mindful eating and stress management techniques. Trackers, group challenges or visual goals can increase engagement, confidence and long-term commitment.

Continued research will be key to translating emerging evidence into effective, gut-targeted diet and lifestyle interventions; subsequently helping to close long-standing research gaps in women’s health. ![]()

Information

To learn more about Yakult Science for Health and to download free resources for healthcare professionals and patients, visit yakult.ie/hcp.

Author

Holly Neill, BSc, PhD, Science Manager at Yakult UK and Ireland.

References:

Ervin S et al (2019). Gut microbial β-glucuronidases reactivate estrogens as components of the estrobolome that reactivate estrogens. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 294(49), 18586–18599. Pollet RM et al (2017). An Atlas of β-Glucuronidases in the Human Intestinal Microbiome. Structure, 25(7), 967–977.e5. Bharadwaj S et al (2015). Symptomatology of irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease during the menstrual cycle. Gastroenterology Report, 3(3), 185–193. Li T et al (2023). A two-sample mendelian randomization analysis investigates associations between gut microbiota and infertility. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 11426. Wang Y & Xie Z (2022) Exploring the role of gut microbiome in male reproduction. Andrology, 10(3), 441-450. Wang J et al (2021). Translocation of vaginal microbiota is involved in impairment and protection of uterine health. Nature Communications, 12(1), 4191. Guo J et al (2022). Gut microbiota in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review. Reproductive Sciences, 29(1), 69-83. Qin R et al (2022). The gut microbiota and endometriosis: From pathogenesis to diagnosis and treatment. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 12, 1069557. Zhang S et al (2023). The role of gut microbiota in the pathogenesis and treatment of postpartum depression. Annals of General Psychiatry, 22(1), 36. Peters BA et al (2022). Spotlight on the gut microbiome in menopause: current insights. International Journal of Women’s Health, 14, 1059-1107. Jiang L et al (2021). Hormone replacement therapy reverses gut microbiome and serum metabolome alterations in premature ovarian insufficiency. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 12, 794496.

Comments (0)