Last week on my podcast, I found myself chatting to dance music legend Norman Cook AKA Fatboy Slim. Despite his most recent gaming memory being a quick blast of Galaxians on a pub arcade machine sometime in the early 80s, we somehow convinced him to join us on a retro gaming/tech podcast, probably because he has always had a fondness for old technology. Fondness might be the wrong word. He cheerfully describes himself as a luddite; he doesn’t own a smartphone, he still listens to music using an iPod, and he is someone who would much rather stick with what works than chase the latest upgrade.

Overpowered by choiceInside outReluctant relationship with techRead more Dan Wood on The EscapistThat attitude took root back in the 80s, when Norm began falling in love with electronic music during his time in The Housemartins. Making that music meant he had to embrace technology, and like many dance music producers of the late 80s and 90s, his weapon of choice (sorry!) became the Atari ST. What surprised me wasn’t that he once used an ST, but that it was still sitting on the desk in the room with him during our interview. The same machine, next to a big box of 3.5” floppy disks full of samples, hooked up to a chunky CRT monitor, it looked less like a modern home studio and more like a freeze-frame from 1990.

Fatboy Slim in his time capsule of a studio

Fatboy Slim in his time capsule of a studio

This isn’t just some museum piece he wheels out for interviews. At the time of writing, a mash-up of his track The Rockafeller Skank and The Rolling Stones has been hanging around the UK Top 40 for several weeks, and it was produced and mixed entirely on that same Atari ST. A song made on a machine released in 1985, charting in 2026!

Overpowered by choiceIt’s Norman’s first chart hit since 2013’s Eat, Sleep, Rave, Repeat (also made on the Atari), but in the time since, based on pressure from peers and friends, he tried to step into the 21st century. He bought a laptop, installed a modern Digital Audio Workstation, and suddenly had access to every drum machine, every instrument, and effectively the entire history of recorded music available at the click of a mouse.

And then nothing happened.

Back when he’d buy a new bit of hardware or come home with a crate of second-hand records, he knew exactly where to start. Give him every sound at once, though, and he froze. He told me he spent two years just staring at a screen, unsure where to begin, paralysed by choice, and in his words, he hasn’t seriously made music since.

It’s a sobering thought. One of the most influential electronic musicians of his generation didn’t stop creating because he ran out of ideas, but because he was given too much choice.

Listening to him describe that creative paralysis, I felt an unpleasant sense of recognition. I don’t make music, but I do play video games, and over the past few years I’ve noticed the same thing creeping into my own habits. Faced with unlimited choice, rather than giving you endless fun, it often feels more like being overwhelmed.

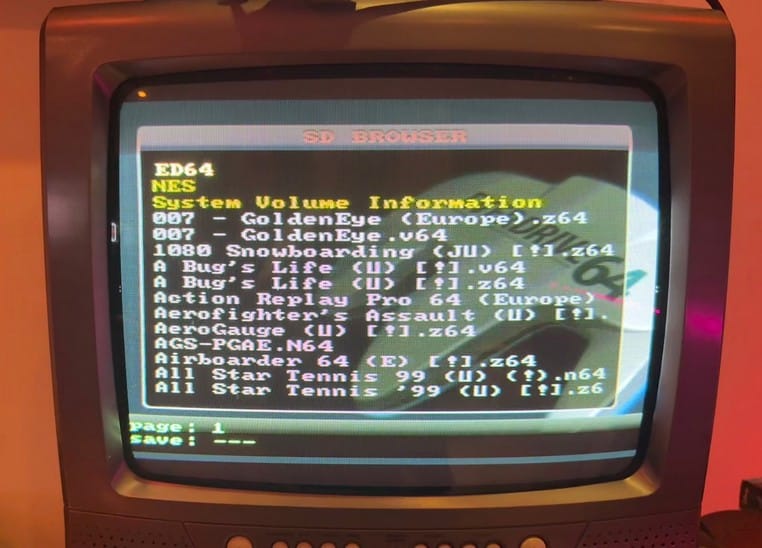

I have flash carts and optical drive emulators for most of my retro consoles and computers. I can switch on my SNES and be greeted instantly by a menu that stretches across several screens, containing every game ever released for the platform, all available at the press of a button. It should be a dream come true; if you had told a 12-year-old me that I would one day have access to this, I wouldn’t have believed it. Instead, though, it makes me restless. While one game is loading, I’m already thinking about the next. I’ll play until I lose a life or two, quickly back out to the menu, scroll, load something else, repeat. Somewhere along the way, playing games turned more into just browsing them.

Flash carts: the thing our childhood dreams were made of

Flash carts: the thing our childhood dreams were made of

When I was a kid, video games felt valuable. Getting a new console game was an event, usually around a birthday or Christmas. My dad would take my brother and me to Electronics Boutique and let us choose a game each. You’d open the box immediately, reading the manual and already anticipating playing it on the bus journey home, long before the cartridge or disc ever got near the console.

They were also expensive. A new Mega Drive game in the early ’90s cost roughly the same as a modern release does today, and that’s before inflation. You were never supposed to own everything. You were supposed to own this game, and make it last for months until the next one came along.

Inside outBecause of that, you spent hours learning your latest game inside out. You memorised its levels, forgave any rough edges, and died over and over again. With no alternative waiting in a menu, you’d just start again.

Which is how my brother and I ended up spending most of the 1994 Christmas holidays glued to Rise of the Robots, a game now remembered less for its quality than for its audacity. It was massively over-hyped, deeply flawed, and nowhere near as good as it was promised to be. But it was the only game we got that Christmas, so we played it non-stop and wrung every last drop of what little entertainment it had to offer.

Today, Pandora’s box is open and there’s no closing it. Entire game libraries for retro systems can be downloaded in minutes and loaded onto a flash cart. Unlimited access isn’t going away, and I don’t seriously believe we can, or should, try to rewind to the 90s. But every so often, a modern gaming experience comes along that quietly reminds me how valuable limits can be. One of my favourite examples of this is the Evercade.

On paper, it sounds almost quaint. A modern, legally licensed retro console built around physical cartridges, each containing a small, human curated selection of classic games. No Internet connectivity, no E-store or DLC, no massive game list menus or the illusion that you’re about to conquer the entirety of gaming history in a single evening.

Each Evercade cartridge is built around a theme, usually a specific publisher, arcade catalogue, or development team. Instead of dumping everything into one place, the games are grouped deliberately. A Data East collection might mix up some arcade classics with lesser-known titles, while an Interplay cartridge pairs familiar PC and console conversions with deeper cuts that might have never crossed your mind to play otherwise. The result feels less like a folder of ROMs and more like a curated exhibition.

One of my favourite Evercade cartridges is the Atari Lynx collection, partly because it mirrors what it was actually like to own a Lynx in the first place. It’s a small, self-contained selection of games, entirely offline, and limited in a way that feels historically plausible. This is roughly what you might have owned (if you were lucky) back in the early 90s, and that context changes everything.

The Atari Lynx collections for the Evercade

The Atari Lynx collections for the Evercade

Because each cartridge only contains a handful of games, you treat them differently. You spend time with them. You approach them with the same patience and respect you did back in the day, not because you’re consciously trying to role-play the past, but because the format encourages it. There aren’t several thousand other games waiting in a menu, there’s no infinite library hovering just out of sight. Just a handful of games, asking to be enjoyed and experienced.

That constraint also nudges you towards games you might otherwise have skipped. I have almost 3,000 games sitting on an SD card in my Amiga 1200, where they’ve lived for well over a decade, yet I’ve probably only played a quarter of them. Faced with that much choice, I inevitably default to the games I already recognise and have played thousands of times over the years. On the Evercade, you can’t really skip half the library without noticing.

It also helps that Evercade doesn’t pretend that every game is a masterpiece. Some of these titles are a bit rough, obscure, or awkward, but they’re historically interesting. You’re encouraged to explore them, to spend time understanding what they are, rather than bouncing off them after thirty seconds because something shinier is waiting in the wings.

Reluctant relationship with techThinking back to that conversation with Fatboy Slim, what stayed with me wasn’t just the novelty of a track made on an Atari ST appearing in the charts in 2026. It was his supposedly reluctant relationship with technology, a reluctance that over time, has clearly turned into something more closely resembling affection. He still uses an old iPod rather than streaming music, not out of stubbornness, but because he prefers knowing exactly what’s on it. He has his own curated library, there’s no algorithm suggesting endless tracks, he doesn’t spend hours “doom-scrolling” suggestions he has no interest in.

It’s the same instinct that keeps his studio tied to a 40 year old machine, and the same one I’ve slowly realised I might be missing when it comes to my game collection. Creativity and enjoyment don’t always flourish when everything is available all at once, sometimes it needs limits.

Retro games haven’t been ruined by abundance, just as music hasn’t been ruined by Spotify, but the way we engage with them has changed. When everything is instantly accessible, it’s easier to keep flicking than to actually sit with something. I see that in my own habits every time I back out to a menu before a game has even had the chance to really introduce itself.

That’s why experiences like the Evercade resonate with me. We’re not going back to a world of two games a year and reading manuals on the bus home, but in an era where Pandora’s box is permanently open, there’s something very appealing about platforms that suggest you close the lid for a while, focus on one thing, and give it the time it actually deserves.

Read more Dan Wood on The Escapist The Escapist is supported by our audience. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn a small affiliate commission. Learn more about our Affiliate Policy

Comments (0)