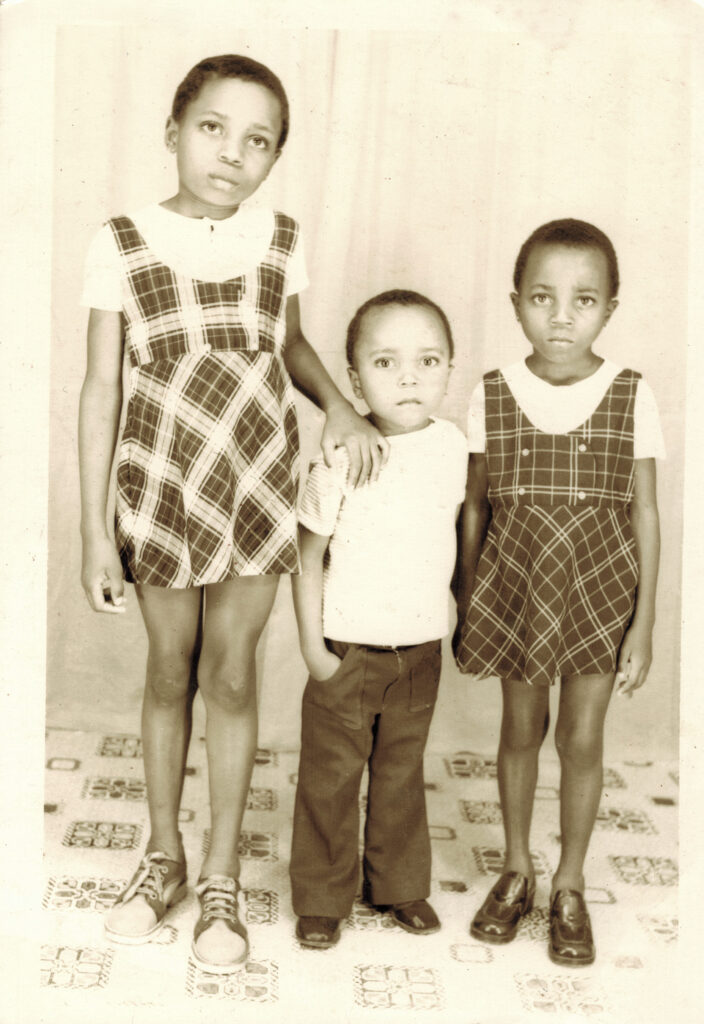

Photograph courtesy of the author.

Papa Mama was a man my age today, but by my standards then, he was an old man. I remember him being small in stature but agile on his feet. He wore slippers. He usually dressed in a Hausa gandoura and chechia, the northern classical attire, and had a chewing stick. And he always spat, which I never liked. He was the one who welcomed clients into the garage and settled transactions. This was when his face would brighten with a happy smile. He would snap back to his angry figure the moment he saw a kid misbehaving around, then would mechanically return to the client.

The day Papa showed up with me, he was in prayer in his small shack. We waited outside. I would never figure out if he lived in the shack or elsewhere, as night never saw me at the garage.

“This is the boy.”

That was how he introduced himself to me, and Papa acquiesced. On our way there, Papa had lectured me, reminding me why I was going to apprentice with a mechanic. He had mentioned my increasing aloofness and said that he hoped I would come down from my daydreams, as “life is tough.” He repeated nlapwut many times.

Truth be told, this going to Papa Mama was a second attempt. Papa had first tried to root me ethnically as a Bamiléké, as Zela’, but bringing his children to Bangangté had only resulted in us, who were born in cities, being stigmatized as tchun bun makup, diasporic.

“Foolish city kids,” we were called by village children, who ridiculed our insecure and accented Medumba. The worse insult, the one that had them come to blows, was to be compared to an animal, we soon learned, the most popular being the warthog. A quite mild slur, by our urban standards. In return, we called them “bush people,” mocked their palm oil smell. In secret, we marveled at their dexterity and at the ingenuity with which they built their toys—mock rotor blades with banana leaves, little cars with bicycle irons, wooden bikes on which they descended hillocks and sometimes made a franc or two carrying vendors’ goods, fall-no-cry hood sleds with ball bearings—borest, they called it, or “park 10,” because it had no braking system. They would roll an old moped tire and squeeze joy out of it. We laughed at the eternal hole those toys created on their shorts, at their ripped pants, and had our revenge when they came out bruised by their intentions, our little hearts boiling with envy. Still, because of the catapults they all always had hanging on their chests, no bird, no squirrel, was ever safe around them. Only an axanthic suspicion made those superheroes run, screaming, “Nyu!”

And when it rained, particularly when sun and rain crossed paths, a rainbow suddenly appeared on the tie-dyed universe and stamped the firmament with its sublime imprint, and they undressed and jumped and flipped in the downpour as their voices exploded in gymnic song,

Nze’nyam tchen bwe men, o! Nze’nyam tchen bwe men! Nze’nyam tchen bwe men, o! Nze’nyam tchen bwe men!

The elephant is giving birth, o! The elephant is giving birth!

The distance between us and the village kids became larger with the years, but our mimicry was our substitute for the toys they had. The city was the real landscape of our existence. Back home in Yaoundé, we danced in the rain too, chanted as well, copied them in many other ways, but we lacked the wide prairies of their games. They had opulent mountains and plains, and we had only a mound, dragonflies, and the Marigot river. They had efflorescent valleys, exuberant grasses, and the perpetual celebration of a gorgeous nature, while our domain was only as large as our yard, with a scrawny frangipani tree near the gate, and sanja wrappers of flowery designs and colors hanging on the numerous clotheslines that stretched from the tree trunks to our tenants’ roof edges.

And I had my after-school football with Félicien that my parents wanted me to stop. Our playing field had its own appeal. When termites flew out of the earth and Mama cooked tak ngu swa for dinner, the tree shot out plumeria flowers with white petals that circled around a yellow center first. Some of them wilted and turned marron on branches, while others were as lively as lit hearths of fire. Chickens and fowls gluttonly waited for them to fall, and when they did, the wind spread their blooms all over our courtyard, mapping out a playing field that became alive at each ball kick. Its scent was humbled only by the miasma of the swamps of our neighborhood that drenched everything else with its permanent fragrance.

Granted, such limits did not stop me: I made plane wings out of a tree leaf and ran holding it in front of me. I jumped to create the illusion of flight. Slid down the hillside, from Nzup Nana’s, our immediate neighbor’s house, where a eucalyptus tree marked my precinct of fun, to the Marigot. With my sister, I watered the path we had created with buckets we carried on our heads.

We used sledders of our own making to mark our way—half-sliced containers, banana leaves—and I still hear our boisterous jumping into the waters, with screams of joy, tantrums, protests of unfairness, wails. I see mud balls flying around, and us roasting palm kernels at the end to soothe our throats. I made a hoop with a tire but fell while chasing it. It smashed one day into the wall of our fence, rolled back, and hit me on the forehead, leaving a little bump that I still carry. I cut my tongue with an improvised knife but still ate the red-hearted guava I was slicing.

***

Going to Papa Mama’s garage was part of a pattern my parents had embarked me on. It was a departure from our village visits, even if the purpose was still to ground me. Before we left home, Mama had told me, “But don’t forget you are a schoolboy.”

She meant, You are not one of those street kids. The same way she would have said, You are not a village kid.

“You are not a nanga boko.” That was what Papa Mama said also, and in Papa’s presence, he added, “Toi pas venir banditer ici.”

The sentence stuck in my mind as the reminder of a red line I was never to cross. The presentation of my options, a Hell of Life or a Life of Freedom, that lay just beyond my new existence outside school and home. Yaoundé! Ongola! I would soon discover that it was Papa Mama’s dictum, for each time he would catch one of his apprentices starting trouble, he would shout, “Toi pas venir banditer ici!”

“Come here,” he would say, “come here, you little bandit.” Enough things were around that he could use as a whip, and he promptly grabbed one. The kid would run and hide between his instruments, in the adjacent sissonghos, among the oily iron pieces of his garage, under the suffocating tent he showed Papa and me, where I could see the piercing eyes of another boy my age who was busy on an oily motor and who promptly looked down when Papa Mama pointed in his direction: “Go work with him.”

To be sure, the running kid would never escape without being civilized, as we called it, except if he ran away from Papa Mama’s garage altogether. That was never going to be an option for me, but I would stay long enough in his garage to receive my share.

I remember Musa, the kid I was to work with, whiningly telling Papa Mama the details of another kid’s mayhems. And him reprimanding the boy, in their mother tongue, I guessed, in fact scolding him for being the crybaby that I too was. Or I hear Musa’s hoarse wailing voice filling the garage, because Monsieur Baba gave him a knock on the head for farting when we were eating together, as we would always do at noon, squatting the northern way around a large plate of varied food.

Papa Mama! I remember his dictum “We never eat alone,” and at the garage we never did. He also taught me that, when faced with a difficulty, the first time I could melt down, but the second time I should laugh, and the third, take it with philosophy. That is, not hit back. In the world of trade, everyone is a potential client, after all. But mostly he taught me the basics of a Muslim life by living it. I learned never to ask him something when he was kneeling for prayer, as he would not even acknowledge me. But I remained curious about his faith and observed him complete his ablutions behind his shack, seated on his calves, and then put on a clean gandura and, with his red chechia on his head, leave the garage for the mosque.

He never asked us kids for more than we could do, and thus he never really had to beat us. He had us all sized up.

His admonition “Toi pas venir banditer ici” was mostly enough.

After Papa left, I was given my task. I was to unscrew some piece of metal I did not know, whose name I was told that day for the first time and soon forgot.

“You screw to the right,” Musa told me with a grin. “And unscrew to the left.”

Monsieur Baba was responsible for the garage. He was a man in his thirties, tall and of an impeccable blackness that we from West and Central Africa associate with Sudanese people. With “real northerners.” To me, he looked like the night watchmen we called Maguida, who slept in front of the shops in our neighborhood. Always dressed in a bubu and large beltless pants, they were known to be armed, and nobody joked with them.

“Do you see the long thing swinging between his legs?” my school chums said about them, giggling. “It is a knife.”

We would hide to better laugh.

Monsieur Baba appeared out of a dusty white Toyota, which he was maneuvering with one hand. He was dressed in used dusty blue overalls marked everywhere with motor oil, had two large circular marks of sweat drawn under his armpits, and smelled of petrol.

If Papa Mama’s voice was rather paternal, his was authoritative. He was the enforcer, and in his vicinity, I understood I had to limit my movements to following his orders and promptly executing them.

Ours was a day of orders anyway, and they were to be performed with speed. Monsieur Baba gave his from under a car, with only his feet visible or his head dug inside the engine of a wrecked vehicle. His hand was then swinging in the air. “Give me the smaller screwdriver.”

I would ask, “Which one does he mean?”

This was where Musa was helpful; he had already spent some time, some years, I would later learn, as an apprentice. “This one.”

“Go fetch some water.”

I already knew where the container full of rainwater stood, even if I had to find an empty bucket.

“Give me that piece of cloth,” I heard Monsieur Baba’s voice say as I was running across the yard, an aluminum bucket in my hand. “Are you sleeping or what?”

Musa was the one being blamed.

When Monsieur Baba came out of his engines, brushed his overalls with two slaps, and cleaned his hands of motor oil with fuel, smiles appeared on our faces, his satisfaction being ours. He was the vivid representation of a successful apprenticeship at Papa Mama’s, and Musa and I were his boys. We would mimic all his gestures, and short of drawing a circular mark of sweat under my armpits, I would do it with zeal. I was very proud of my first day at the garage and did not change to go home. Look, I was not useless! I was not one of those individuals trapped by the weight of nothingness, of whom Mama would say, sulking and shaking her head, “A mi mbe.”

If they prayed before their door or in their backyard during the day, all the northerners went to the sunset prayer at the Great Mosque of the Briqueterie, which marked the end of my working day. They went as a group, their multicolored gandouras floating in the dust, their chechias round flecks in the distance, counting the beads of their tasbihs. I walked back home alone, to Nkomkana, in the all-embracing sound of the call to prayer, my pants showing spots of filth. Having cleaned my hands of motor oil with petrol like everyone else at the garage, I smelled sufficiently like a mechanic to impress my sisters. But I wanted more. I wanted our neighbors, I wanted the city, to see me drenched in slime. Of course, Mama was not fooled by my theatrics, and in the days to come, I was to discover the seriousness of the life of an apprentice.

At least I had escaped her grip.

***

Papa always listened to the radio. I fell asleep at home to its sound coming from his camphor-smelling bedroom. I had radio dreams. That electric guitar I still zoom on, the Eagles’s “Hotel California,” tout est occupé. Years later that song would spark my love for Makokwa, for Mako. We were in her student hostel back then in Germany, and I was cooking and singing. She was amused that I could not measure food, had cooked for ten, but I had a valid excuse, or so I thought. “I had a lot of siblings, dear. Nine mouths to feed for my mother.” That day I had said, “No pasta”; it is Cameroonian food on the menu, fried sliced plantain, the gold medal of a Cameroonian bachelor in the diaspora. Cameroonian dish, American song. Tout est occupé. She laughed at the mistranslation I had carried along from my childhood. Yaoundéans improvise on words spoken in languages we do not understand, I informed her. A necessity in our Babel of the Tropics, “Oh, yes, Yaoundéans do not understand most of the languages spoken around them.”

“Really?”

“We just guess along. We go with the flow.”

Before her, no one had corrected me. It took Mako, who is now my wife, for me to hear the right line. After twenty-five years of marriage, we still laugh about that Cameroonian paradise of just guessing around that I had started describing that day. Such a lovely place indeed, hidden for thirty years inside a mistranslation.

As a child, I did not care. Like all Yaoundéans, I still do not. Music is the soundtrack to my life, when I write, when I read, when I work. When I was growing up in Nkomkana, music was always around me, pumping its lyrics from the multiple bars around our house, from the cassette vendor in front of Mama’s shop, from the taxis speeding on the Nkomkana–Tsinga road, all windows open and the forceful voice of Nkotti François bewitching our city’s blue sky with Toto Guillaume’s unsurpassable love anthem to his mother, Na dia ne nyongi, Na dia ne nyongi! For twenty years music in foreign tongues has clothed my commute and made it bearable. Who needs a dictionary to understand Taylor Swift?

At ten, I woke up to the radio playing in our yard, with the singing voice of Mama or of my aunt Nja Jacka coming out of the kitchen, and I was welcomed to the garage each morning with songs from Papa Mama’s transistor. His songs were peculiar, though; they were shrill, and the speaker’s voice came in waves. It sounded like a call from a distant place—not like the call to prayer from the Briqueterie mosque, but close to it. It too spoke in a language I did not understand.

For Papa Mama was Chadian. He was a refugee from the civil war that was tearing his country apart. I learned it the day the Chief came into the garage and started throwing all the instruments down from the cupboard and table.

His voice was thunder in the yard. “Instead of being thankful to be here, look how you behave.”

He was livid, and our garage gave his tempestuous personality a morning stage.

“Do you think I am the one to feed you in this country?” he yelled, flinging a metal piece into the street. “Am I the one who started the war in your country?”

I had not dressed in my garage clothes yet. The yard was full of onlookers. Women stopped on their way to the market and traded words, asking what was happening. The bar owner next door paused, shaking his head, his keys in his hands. The boys who washed cars in the morning down the street, the cigarette and fruit vendors who occupied the crossroad, were all in our yard. They were whispering among themselves, a smile drawn on their lips and their eyes following the scene. Musa soon joined me in my corner. We did not know what else to do but witness a man’s wrath.

The morning ruckus made me see the Chief’s face up close for the first time. The first man I had seen using a telephone, he was usually on his balcony, the listener on his left ear, grimacing and making sounds, owe, owe, and then, zooming, uuuuuuh, tetetete. He was always deep into a paraverbal conversation with some faraway person. The closest I got to hearing his voice was when I heard him say, be, tan, fok, la, with intervals, and allo! allo! To call to somebody on the street from up where he was, he would whistle and wag his index finger, whether to give an order or say a threat.

This day was different. He was down among the cars of Papa Mama’s garage and was still raging. With his cane, he slammed one pole of the tent and it all collapsed, making all the chickens and guinea fowls run away.

Papa Mama was walking behind him, his demeanor one of defeat, his hands held in supplication. His lips were stammering words I could not make out, but that the Chief echoed for us all to hear, opening his hands, waving his cane, looking around, and speaking in a loud voice. They walked between dusty cars with flat tires, dirty trucks with broken windows or open fronts. Having seen the Chief unleash his destructive mood, I was afraid he would add to the debris around by smashing a window or throwing down the container full of rainwater. But between the cars, he seemed to master his overflowing anger.

“No,” he was saying, agitating just one hand. “It is enough! I do not want to see your engines in my yard anymore. Can you even imagine how dirty your garage is? Can you figure out how much money I lose by having your dusty hardware lying around everywhere? Do you even know what kind of neighborhood you are in here? My God, this is Tsinga-Oliga, not the Hausa quarter! Instead of practically giving it to you for free like I do, I could sell just parcels of this ground to a Bamiléké man and make millions! It is a facade! I could rent it to white people like they do down the Mfoundi valley there, yes, and make tons of money!”

He stopped behind a yellow Toyota without tires. It was mounted on concrete blocks.

“Look at this,” he said, pointing at the car with his cane and gesturing to everyone around. “Look at this.”

Someone had drawn a heart and an arrow on the dusty windshield, with the word amour. Love.

“What are you looking at?” Monsieur Baba’s voice yelled at us apprentice boys from behind us.

He too had rushed out from his engines because of the Chief’s voice. We ran between the cars and engines and busied ourselves on the table of instruments, but the Chief’s words occupied the air.

“Is it the way you do in your country?” he asked. “You come here and use our hospitality to soil us. Can you do that in Chad?”

I saw Tchié come out of their house. He talked to his father in their mother tongue. The Chief made gestures of exasperation; Papa Mama drew a face of commiseration. People joined in, and the loud voice was toned down.

The Chief protested, in French. “No, no,” he was saying. “Trop c’est trop.”

But the neighborhood prevailed.

From Scale Boy: An African Childhood, to be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in January.

Patrice Nganang is a novelist, a poet, and an essayist. His novel Dog Days received the Prix Marguerite Yourcenar and the Grand Prix littéraire d’Afrique noire. He is also the author of Mount Pleasant, When the Plums Are Ripe, and A Trail of Crab Tracks. He teaches comparative literature at Stony Brook University in New York.

Comments (0)