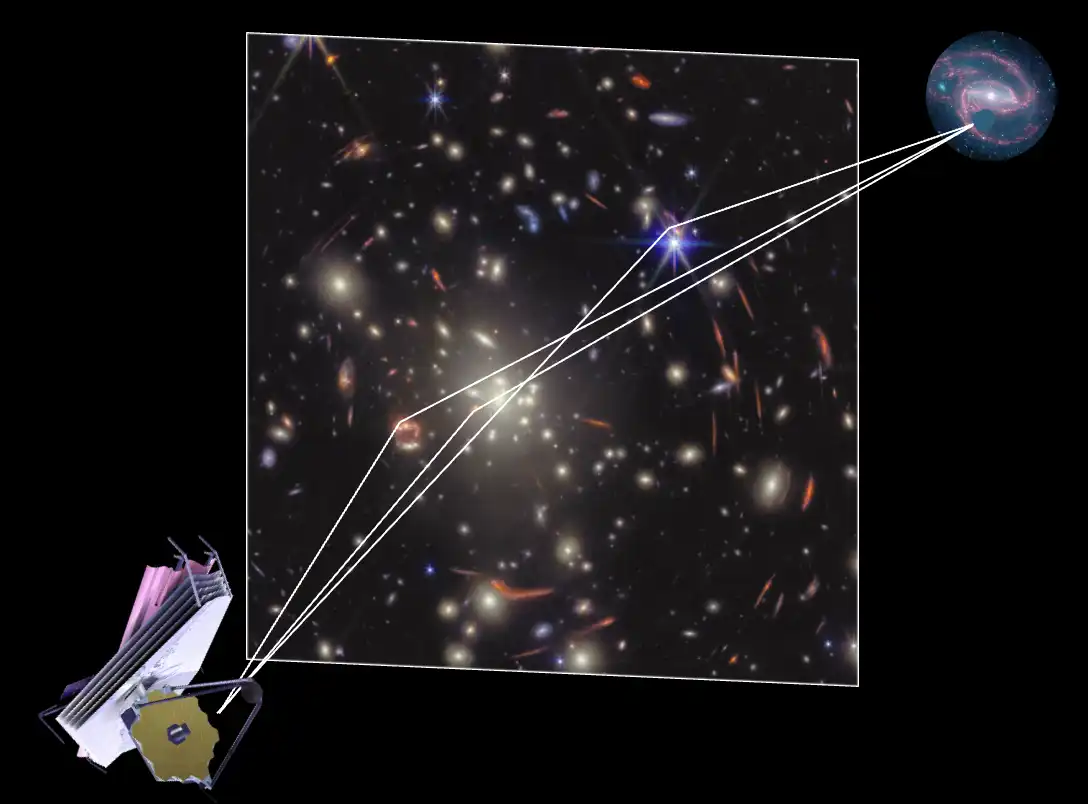

The galaxy cluster MACS J0308 acts as a lens for Supernova Ares.

The galaxy cluster MACS J0308 acts as a lens for Supernova Ares.Sixty years from now, photons from an exploded star will arrive at Earth. Astronomers can make that prediction because they’ve already seen it happen: The James Webb Space Telescope captured light from a supernova, named Ares, that exploded in the distant universe. According to astronomers’ predictions, two identical images have yet to appear.

The trick is that Supernova Ares went off behind a galaxy cluster. Its mass acts like a giant cosmic lens, splitting the supernova’s light into multiple images. While some photons have already hit Webb’s detectors, others are taking the scenic route, bending on a decades-longer path around the foreground cluster. Along with other lensed supernovae like it, Ares could break through a current stand-off in cosmology by providing a measure of the universe’s current rate of expansion.

Representation of the lensing effect of the MJ0308 galaxy cluster which causes multiple images of the SN Ares host galaxy to appear. SN Ares is set to return in ~ 60 years in the images nearest the center of the galaxy cluster. The closer the light comes to the center, the larger the delay from gravitational time dilation.

Representation of the lensing effect of the MJ0308 galaxy cluster which causes multiple images of the SN Ares host galaxy to appear. SN Ares is set to return in ~ 60 years in the images nearest the center of the galaxy cluster. The closer the light comes to the center, the larger the delay from gravitational time dilation. “This was a massive stellar explosion . . . that occurred when the universe was about a third of its current age,” said Conor Larison (Space Telescope Science Institute) at a press conference at the 247th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Phoenix, Arizona.

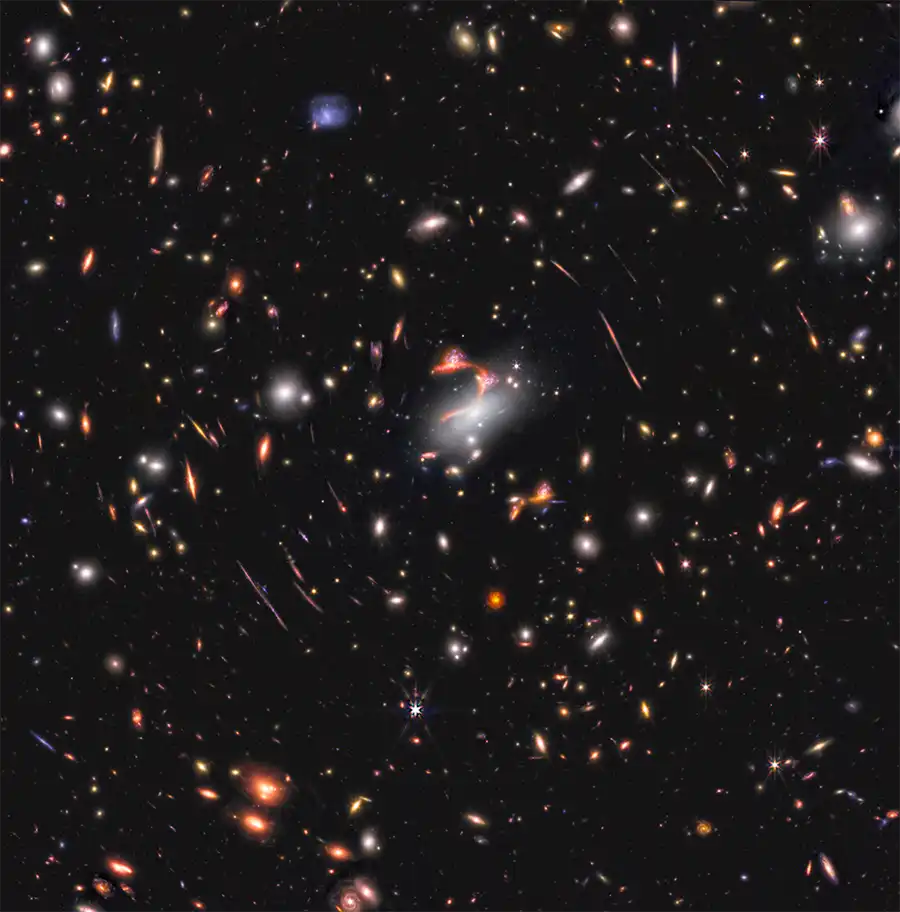

Larison showed several images from a James Webb Space Telescope program, the Vast Exploration for Nascent, Unexplored Sources (VENUS), led by Seiji Fushimoto (University of Toronto). VENUS will image 60 galaxy clusters, using them as gravitational lenses to cosmically magnify objects in the distant universe. The project follows on the Hubble Space Telescope’s Frontier Fields, a groundbreaking effort that imaged six galaxy clusters at similar levels of detail. Besides imaging more clusters, the VENUS program also extends farther into the early universe with Webb’s infrared reach.

Each of VENUS’s 60 galaxy clusters magnifies the distant universe, in the same way that the bottom of a wine glass magnifies the surrounding room. (Just remember to drink the wine first!) The glass acts a lens, distorting incoming light, even creating multiple images.

When the cluster lens splits a background supernova’s light into identical images, the photons that create those images take different paths through the expanding universe before they arrive at Earth. Some images arrive earlier, while others are delayed. The time different photons take en route to Earth can shed light on the nature of cosmic expansion.

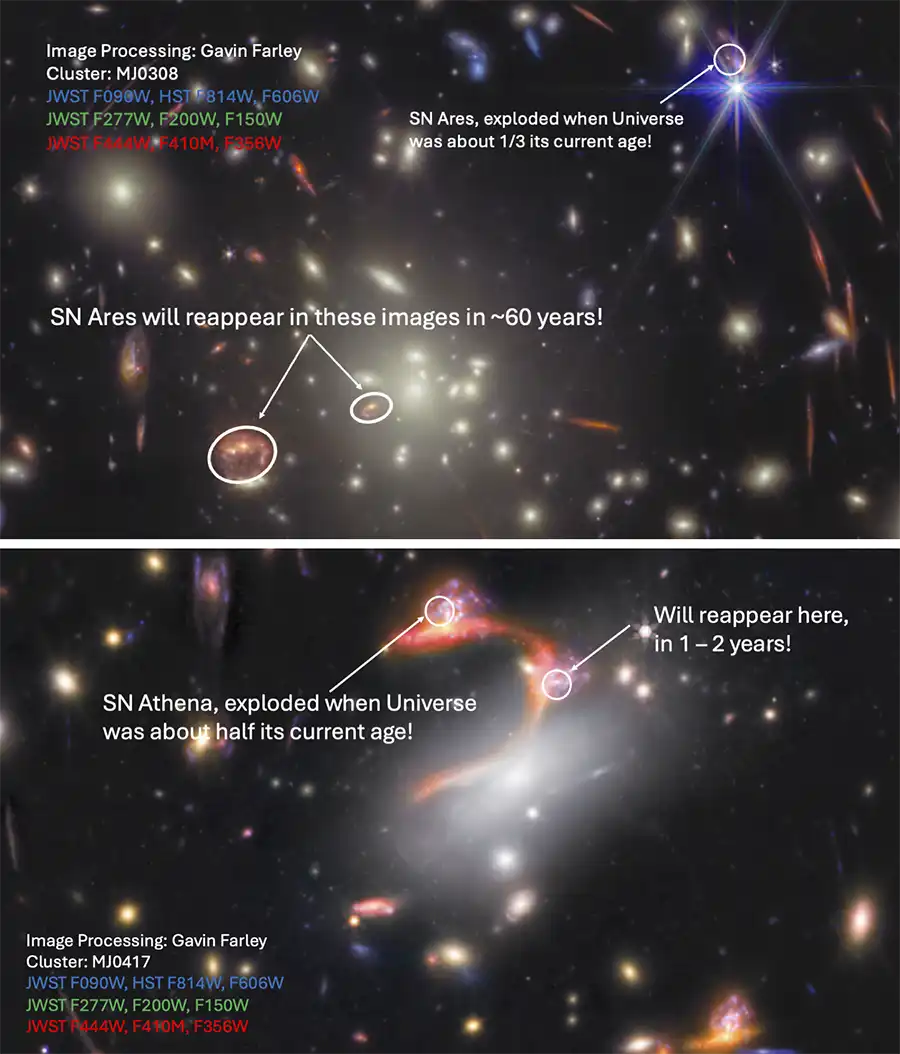

In the case of Supernova Ares, magnified by the cluster MACS 0308, only one of three expected images has appeared. Any cosmological implication from the multiple images awaits the arrival of the other two, decades in the future.

“We don't necessarily know what the cosmological question of the day will be in 60 years,” Larison said at the conference. “But one thing is certain, this will be the most precise time-delay measurement that we know of currently that we can make.”

The galaxy cluster MACS J0417 acts as a lens for Supernova Athena.

The galaxy cluster MACS J0417 acts as a lens for Supernova Athena.Astronomers have known that deep images could capture lensed supernovae as they happen since Sjur Refsdal (Hamburg Observatory, Germany) first suggested it in 1964. But it wasn’t until a decade ago that astronomers found their first real example, fittingly named Supernova Refsdal. Just a few months after its discovery, the predicted fifth image arrived. Other discoveries have trickled in through the years (including iPTF 16geu, Requiem, Hope, and most recently, a lensed superluminous supernova named 2025wny).

But Supernova Ares tops them all. Its distance measurement, based on the time delay, will be 100 times more precise than the best estimates we have of lensed supernovae today, Larison says.

Supernova Ares isn’t the only stellar blast to be found behind the VENUS galaxy clusters so far. Another is Supernova Athena, behind the cluster MACS J0417. Fortunately, we won’t have to wait a full 60 years for all of its light to arrive. The team expects another image to arrive in another year or two — and Webb will no doubt be watching.

Color images composed of Hubble Space Telescope (HST) and James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) observations of the MJ0308 and MJ0417 galaxy clusters in which SN Ares and SN Athena were discovered, respectively. Both SNe will reappear in other lensed images, allowing for precise cosmological constraints.

Color images composed of Hubble Space Telescope (HST) and James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) observations of the MJ0308 and MJ0417 galaxy clusters in which SN Ares and SN Athena were discovered, respectively. Both SNe will reappear in other lensed images, allowing for precise cosmological constraints. While astronomers can use a single lensed supernova to calculate something like the current expansion rate of the universe, termed the Hubble constant, the answer won’t necessarily be precise enough to be useful.

And it needs to be useful, because astronomers have been trying to measure how fast the universe is currently expanding — and coming up with different answers — for decades. Current estimates differ by as much as a few percent, depending on how the Hubble constant is measured.

But in a single supernova, it’s difficult to measure the exact arrival time of photons across two different images, unless you catch the blast right as it begins to brighten. Even more difficult to wrangle with is the optics of the galaxy cluster lens, which is more complex than the optics of a telescope (or a wine glass, for that matter). To understand those optics, astronomers need to know exactly how a cluster’s mass is distributed.

Finding more lensed supernovae, and especially finding them behind well-studied clusters, can help. In addition to Ares and Athena, the researchers have also found four other lensed supernovae whose images are all present and accounted for, and more are expected as the observing program continues.

“Eventually, when we have enough of these [lensed supernovae], maybe around 20, we'll be able to reach a total precision that’s comparable to our best current cosmological distance indicators,” Larison says.

And if larger samples don’t do the trick, well, we can always wait for the next images of Supernova Ares, due to arrive in 2086.

Comments (0)