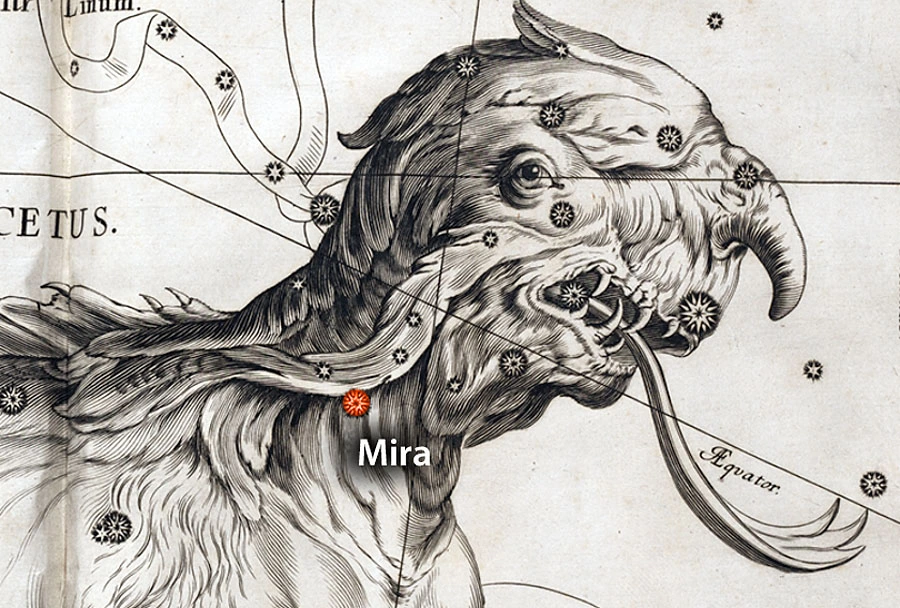

David Fabricius discovered Omicron Ceti's variability in 1596. It received its official name Mira — the Wonderful — in 1662 from Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius. It's located in the neck of Cetus, the Sea Monster, depicted here in Hevelius's 17th-century star atlas and catalog Prodromus Astronomiae.

David Fabricius discovered Omicron Ceti's variability in 1596. It received its official name Mira — the Wonderful — in 1662 from Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius. It's located in the neck of Cetus, the Sea Monster, depicted here in Hevelius's 17th-century star atlas and catalog Prodromus Astronomiae. There are few naked-eye stars as wonderful or surprising as Mira. It's the first pulsating variable star to be discovered. Pulsating, or Mira, variables are unstable red giants that physically contract and expand in size, causing their brightness to vary cyclically, typically between 80 and 1,000 days.

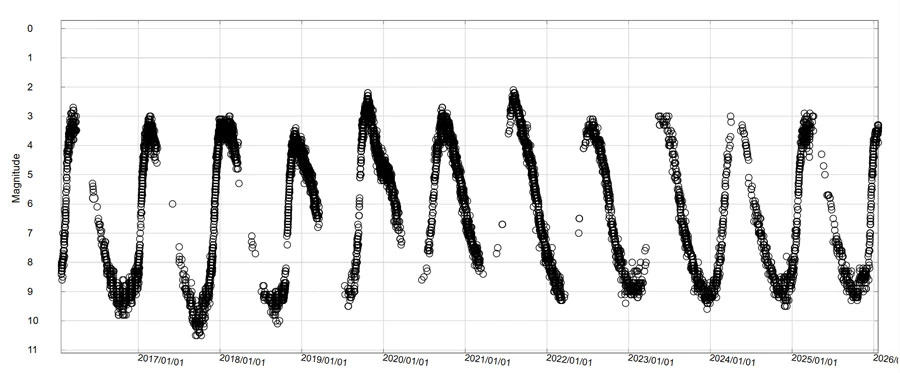

Mira continues to surprise me to this day. Its light varies across 8 magnitudes over a period of about 332 days. At its maximum, the star gleams at magnitude 2 and rivals Polaris, but at minimum it dips as low as 10th magnitude. Both its period and amplitude — how bright or faint it will become — varies from cycle to cycle. When contracting, the star heats up and brightens. When expanding, it cools and dims.

Occasionally, I'll lose track of the red giant, but last month I happened to look up into Cetus (Mira's home). Normally, I would expect to see blank sky since Mira is below naked-eye visibility for months. Instead, it winked back matter-of-factly. I always feel a ping of pleasure when this beating heart returns to view.

Mira-like stars are unstable, with pulsations driven by the interplay between the outward pressure produced by fusing hydrogen and helium gases in the star's interior and gravity's inward pull. Gravity compresses the star, heating the interior until enough pressure builds up to push back and force the outer layers of the star to expand, cool, and dim. With the pressure relieved, gravity pulls the envelope back in to begin another cycle.

Mira-like stars are unstable, with pulsations driven by the interplay between the outward pressure produced by fusing hydrogen and helium gases in the star's interior and gravity's inward pull. Gravity compresses the star, heating the interior until enough pressure builds up to push back and force the outer layers of the star to expand, cool, and dim. With the pressure relieved, gravity pulls the envelope back in to begin another cycle.David Fabricius undoubtedly felt the same. The German astronomer was the first to detect Mira's variability. On August 3, 1596, he was attempting to fix Jupiter's position in relation to its neighboring stars. At the time, the planet was in the morning sky in Aries about 20° northeast of the variable. Mira was a great choice since it was close to 2nd magnitude, its peak brightness. But when Fabricius attempted to look the star up, he found no depiction of it on his celestial globe nor reference in any of his books. For a brief time, he thought it could be a comet. In a letter to fellow astronomer Tycho Brahe, he shared his speculation:

"I saw in the southern direction in the constellation Cetus an unusual star that was never seen in this size [brightness] at that location, so that from a closer inspection of the location I immediately thought that it could be a newly appeared comet."

Besides a comet, he also referred to the object as stella nova — Latin for "new star". In August and September that year, Fabricius reobserved Mira and noticed its light had dimmed. Since its fading coincided with Jupiter moving west in retrograde motion, Fabricius surmised that the two were somehow connected — Mira grew brighter when Jupiter moved in prograde (eastward) motion and dimmed as the planet went into retrograde.

After these observations, he ignored the star for some 12 years, likely thinking it was a temporary phenomenon. But in February 1609, while observing Jupiter and Venus prior to their upcoming March conjunction, Fabricius was surprised to see a new star in the neighborhood. Checking its position, he realized it was the same object he first spotted in 1596! The fact that Jupiter — with an orbital period of 12 years — was nearby and in prograde motion seemed to confirm his hypothesis that the two were indeed related. In a letter to Johannes Kepler, you can feel his thrill at having seen something so remarkable twice:

"I had observed in Aug and Sep of the year [15]96, and which was not seen any more by myself since then. Wonderful

thing!"

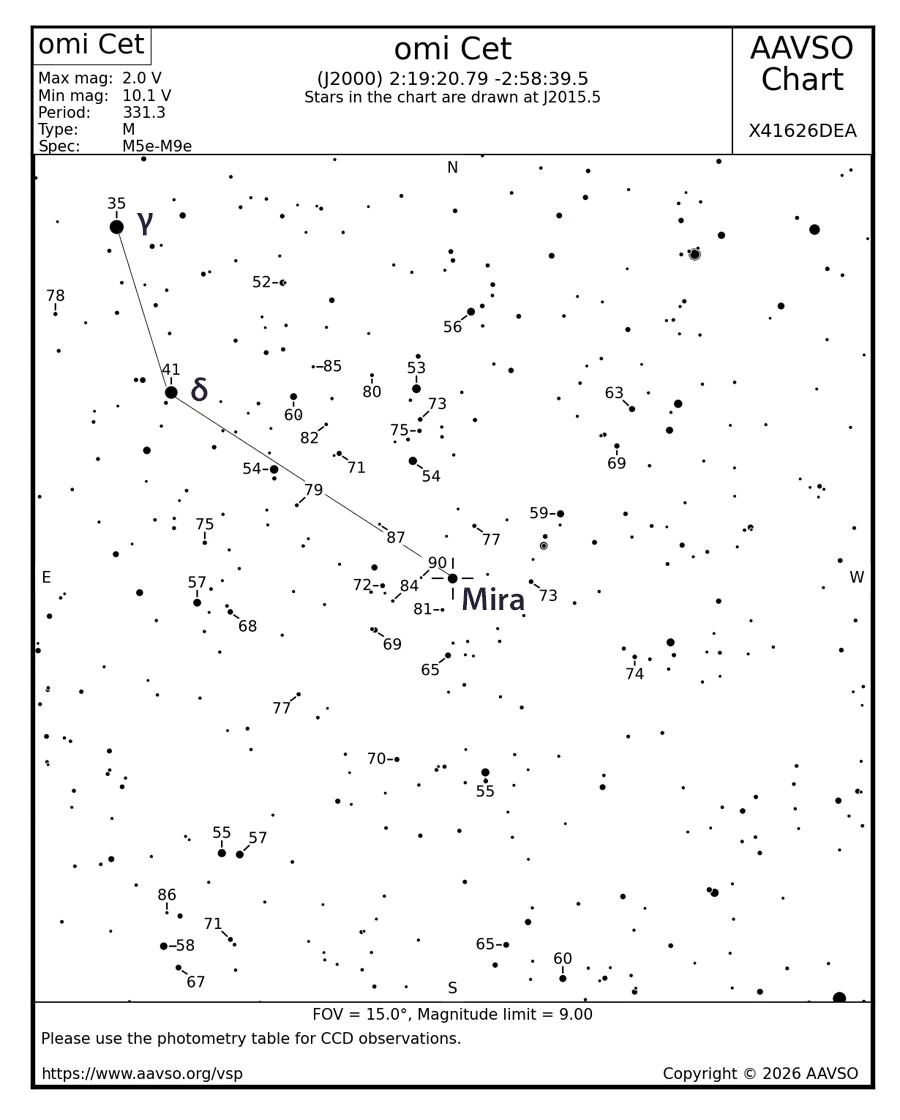

Use this map from the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO) to locate Mira and estimate its changing brightness. Magnitudes are shown with the decimal points omitted to reduce clutter. For more charts, drop by the AAVSO website, type Mira in the Pick a Star box, and then click Create a finder chart.

Use this map from the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO) to locate Mira and estimate its changing brightness. Magnitudes are shown with the decimal points omitted to reduce clutter. For more charts, drop by the AAVSO website, type Mira in the Pick a Star box, and then click Create a finder chart.To encapsulate its amazing and wonderful behavior in a word, Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius named it Mira, Latin for "wonderful" or "astonishing". It also goes by the designation Omicron (ο) Ceti. Star maps often show it as an open circle instead of a solid dot to indicate its brightness fluctuates. When I first saw Mira this season on Christmas Eve 2025, it shone at magnitude 5.0. Because it tends to brighten fairly quickly when approaching maximum light, when I returned next on January 7th it had vaulted to magnitude 3.6. Peak brightness is expected around February 7th.

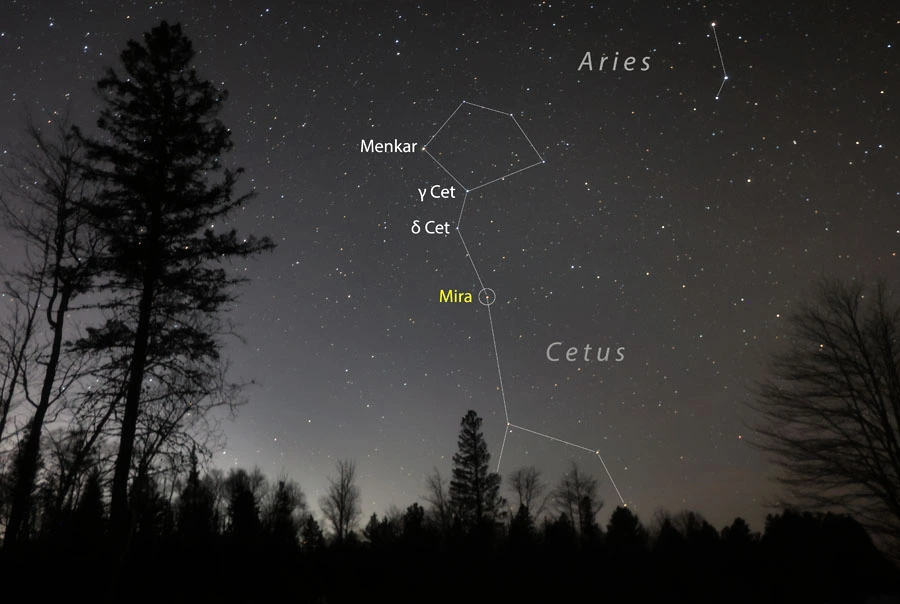

Mira shines just west of the meridian, about halfway up the southern sky at nightfall in mid-January. When I took this photo the variable glowed at magnitude 3.6. For a challenge, try to discern the star's color with the unaided eye around maximum.

Mira shines just west of the meridian, about halfway up the southern sky at nightfall in mid-January. When I took this photo the variable glowed at magnitude 3.6. For a challenge, try to discern the star's color with the unaided eye around maximum.As of January 21st, most observers reporting to the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO) put it around magnitude 3.4 to 3.5. Mira's pretty easy to see in a relatively dark sky and shows up well in a 10-second time-exposure on a smartphone. But if you need help, just use binoculars. Cetus is a big constellation with a lot of dim stars that stands nearly due south at the end of evening twilight.

If you've never seen this wonderful star, start by locating the Pleiades cluster and nearby 1st-magnitude Aldebaran. Connect them into a triangle with Menkar, Alpha (α) Ceti, located about two outstretched fists (20° to 25°) to the southwest. Mira lies 13° southwest of Menkar on a line through Delta (δ) Ceti (magnitude 4.1). This star and neighboring Gamma (γ) Ceti (magnitude 3.5) make excellent comparison stars for gauging the variable's current brightness. Should Mira surpass Gamma Ceti, use Menkar (2.5).

Mira's light curve, shown here from 2016 (far left) through early January 2026 (far right), illustrates how its highs and lows vary from cycle to cycle. Magnitude runs along the Y axis with dates along the X axis. Mira lies about 300 light-years from Earth and spans approximately 400 times the radius of the Sun. During a pulsation cycle its radius can vary up to 50% in visible light.

Mira's light curve, shown here from 2016 (far left) through early January 2026 (far right), illustrates how its highs and lows vary from cycle to cycle. Magnitude runs along the Y axis with dates along the X axis. Mira lies about 300 light-years from Earth and spans approximately 400 times the radius of the Sun. During a pulsation cycle its radius can vary up to 50% in visible light. At maximum, Mira can be as bright as magnitude 2 or dimmer at about 3.5. Every cycle carries with it a sense of anticipation of the unknown. The star last reached 2nd magnitude in 2021. What it will do this time is anyone's guess. After peaking, the red giant starts its slow decline to minimum, fading at a much slower rate than when it rose. A 60-mm telescope will let you track to the nadir of its cycle.

Like comets, Mira and its pals, which include R Leonis, Chi Cygni, and many others, add a dash of unpredictability that makes them fascinating to watch. As they huff and puff their way to white dwarf-hood, these bloated oldsters release carbon fused in their cores into space, making creatures like us who monitor their behavior possible. We are the bee to Mira's flower.