The Bullet Cluster, imaged here by the Dark Energy Camera mounted on the Victor M. Blanco 4-meter Telescope at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, is made up of two colliding galaxy clusters in the constellation Carina. These galaxy clusters act as gravitational lenses, magnifying the light of background galaxies. (View a zoomable image to explore this galaxyscape in more detail.)

The Bullet Cluster, imaged here by the Dark Energy Camera mounted on the Victor M. Blanco 4-meter Telescope at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, is made up of two colliding galaxy clusters in the constellation Carina. These galaxy clusters act as gravitational lenses, magnifying the light of background galaxies. (View a zoomable image to explore this galaxyscape in more detail.)The astronomers behind the Dark Energy Survey have measured the properties of the mysteriously repulsive dark energy more precisely than ever before. Their work brings together six years of data, more than half a billion galaxies, and thousands of supernovae to shed light on crucial questions in cosmology.

Since 1998, astronomers have known that the expansion of the universe is accelerating. They aren’t sure why, but it’s usually put down to the existence of a repulsive property of empty space, labeled dark energy. But the nature of dark energy — whether it evolves over time or expands space in a more constant fashion — has remained an open question.

Back in 2013, astronomers started using the Dark Energy Camera attached to the Víctor M. Blanco telescope in Chile to begin the Dark Energy Survey (DES) to try to answer that question. Over the next six years, DES astronomers observed an eighth of the sky across a total of 758 nights, cataloguing 669 million galaxies. The full set of findings is posted on the collaboration’s website and will appear in Physical Review D.

“These results from the Dark Energy Survey shine new light on our understanding of the universe and its expansion,” says Regina Rameika (U.S. Department of Energy).

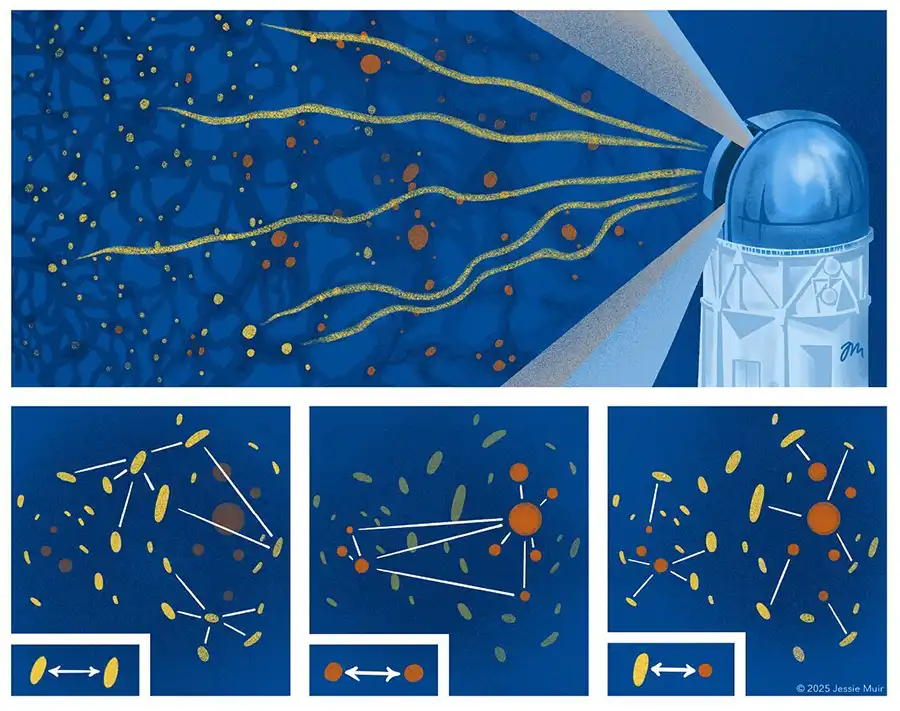

DES scientists analyzed the distribution of matter by measuring the shape of distant galaxies, shown in yellow, as well as the positions of galaxies, shown in red.

DES scientists analyzed the distribution of matter by measuring the shape of distant galaxies, shown in yellow, as well as the positions of galaxies, shown in red. One of the ways astronomers used DES to measure dark energy is through an effect known as weak lensing. In this effect, the gravity of intervening matter, most of it dark matter, slightly bends light from distant galaxies, subtly distorting their shapes. Astronomers must observe many galaxies to measure the effect.

Measuring weak lensing with DES allowed astronomers to chart the distribution of dark matter over the last 6 billion years. If dark energy is ramping up the expansion of the universe, it should slow the growth of large-scale structure, such as galaxy clusters, later on in cosmic evolution.

Dark energy also has a silent, guiding hand in shaping the distribution of galaxies. So analyzing the statistical pattern of their clustering is another way astronomers measure the repulsive force’s changing influence.

The DES team combined six years’ worth of weak lensing and galaxy distribution data with other datasets (based on baryon acoustic oscillations and Type Ia supernovae). It’s the first time all four methods for measuring dark energy have been combined in this way.

“This was something I would have only dared to dream about when DES started collecting data,” says DES team member Yuanyuan Zhang (NSF NOIRLab). “Now the dream has come true.”

The results are intriguing.

While consistent with findings from previous releases of DES data, the new findings widen the possible explanations for dark energy. In the standard model of cosmology, the density of dark energy is constant. While these new data fit that picture, they fail to rule out the alternative theory, in which dark energy evolves over time.

But both theories face a deeper problem: They fail to accurately predict how matter has clustered in recent astronomical history. Observations of the early universe suggest that cosmic structure ought to be clumpy. Yet images of our cosmic neighborhood show that galaxies are more smoothly distributed than expected. The new DES data only widen this gap.

“This tension has previously been observed by several independent surveys and remains one of the most intriguing open questions in cosmology,” says Edward Macaulay (Queen Mary University of London), who was not involved in the research.

Macaulay thinks the DES results are an amazing treasure trove, but he also thinks this is just the start of something bigger. “Although this paper represents the end of observations with DES, it's just the start of a whole new golden age of cosmology,” he says. New observations from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI), the Euclid spacecraft, and the 8.4-meter Simonyi Survey Telescope at the Vera Rubin Observatory represent a step-change in our efforts to pin down the nature of dark energy.

“With this new generation of telescopes,” Macaulay says, “we have an extraordinary opportunity to discover more about the biggest questions in cosmology.”

Comments (0)