Past mass extinctions, as devastating as they are, have shaped the vast biodiversity of today’s Earth by reshuffling the evolutionary cards. The Late Ordovician Mass Extinction (LOME), 445 million years ago, was the first of five mass extinction events our planet has undergone (so far), wiping out around 85 percent of all marine species by a sudden Ice Age.

While many species found their untimely end, one group of fish that survived began to take over ecosystems left behind. They shared a distinct feature that would go on to play a major role in the evolution of countless species to come: jaws.

A research team from the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST) combined fossil data from around the world to confirm what gave jawed vertebrates the opportunity to expand globally in a new study published in Science Advances.

“This work helps explain why jaws evolved, why jawed vertebrates ultimately prevailed,” said senior author Lauren Sallan, professor of the Macroevolution Unit at OIST, in a press release, “and why modern marine life traces back to these survivors rather than to earlier forms like conodonts and trilobites.”

Life 450 Million Years AgoDuring the Ordovician period (486 million years to 443 million years ago), the southern supercontinent Gondwana was surrounded by warm, shallow seas under a greenhouse climate, with ice-free poles.

Illustration of Sacabambaspis.

(Image Courtesy of Nobu Tamura/CC BY-SA)

These oceans were packed with strange life, from lamprey-like conodonts and trilobites to human-sized sea scorpions and giant nautiloids. Early plants and arthropods were only just beginning to colonize land, while jawed vertebrates (gnathostomes) remained rare and inconspicuous.

“While we don’t know the ultimate causes of LOME, we do know that there was a clear before and after the event,” said Sallan.

The extinction struck in two phases: an abrupt shift to an icehouse climate that drained shallow seas, followed by rapid warming that flooded oceans with oxygen-poor, sulfur-rich water, devastating marine life.

Read More: Are We Really on the Brink of a Sixth Mass Extinction?

From Small Refuges to Taking Over the WorldAfter these huge shifts the surviving vertebrates stuck to refugia, teeming with isolated biodiversity hotspots and separated by deep ocean. Within these stable pockets, surviving gnathostomes appear to have had an advantage.

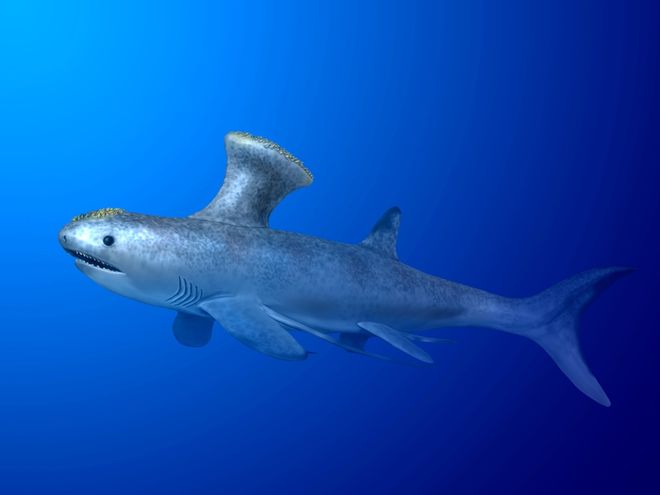

Illustration of Akmonistion, jawed fish that started appearing in the Silurian period right after LOME.

(Image Courtesy of Nobu Tamura/CC BY-SA)

“We pulled together 200 years of late Ordovician and early Silurian paleontology,” said first author Wahei Hagiwara, Ph.D. student at OIST in the release, “creating a new database of the fossil record that helped us reconstruct these ecosystems.”

The team quantified diversity through time and found a clear pattern: The extinction pulses were followed by a gradual but dramatic rise in gnathostome biodiversity over several million years.

“This is the first time that we’ve been able to quantitatively examine the biogeography before and after a mass extinction event,” explained Sallan.

By tracing where species lived and how they moved, the researchers identified specific refugia that played an outsized role in vertebrate evolution. In what is now South China, they found the earliest full-body fossils of jawed fishes related to modern sharks. These species remained confined to stable refuges for millions of years before evolving the ability to cross open oceans and spread globally, explained Hagiwara.

Jawed Vertebrates Ultimately Won OutRather than wiping the slate clean, the Late Ordovician Mass Extinction triggered an ecological reset. Early vertebrates stepped into niches left vacant by extinct jawless vertebrates and other animals, rebuilding similar ecosystem structures with new species.

“Did jaws evolve in order to create a new ecological niche, or did our ancestors fill an existing niche first, and then diversify?” asked Sallan. “Our study points to the latter.”

The researcher’s work combines location, morphology, ecology, and biodiversity, helping to paint the picture of how ecosystems from millions of years ago recovered and reshaped after a major extinction event.

“We have demonstrated that jawed fishes only became dominant because this event happened,” said Sallan.

Read More: Living Fossils Like the Coelacanth Have Remained Unchanged for 400 Million Years

Article SourcesOur writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article: