Francine Uenuma - History Correspondent

:focal(721x457:722x458)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/39/c3/39c32aa1-7242-46df-aa4d-d732c768c090/eliza2.png) MIT professor Joseph Weizenbaum developed Eliza in the mid-1960s. His views on artificial intelligence were often at odds with many of his fellow pioneers in the field.

Illustration by Meilan Solly / Images via Newspapers.com, Adobe Stock and MIT

MIT professor Joseph Weizenbaum developed Eliza in the mid-1960s. His views on artificial intelligence were often at odds with many of his fellow pioneers in the field.

Illustration by Meilan Solly / Images via Newspapers.com, Adobe Stock and MIT

It could have been a heart-to-heart between friends.

“Men are all alike,” one participant said. “In what way?” the other prompted. The reply: “They’re always bugging us about something or other.” The exchange continued in this vein for some time, seemingly capturing an empathetic listener coaxing the speaker for details.

But this mid-1960s conversation came with a catch: The listener wasn’t human. Its name was Eliza, and it was a computer program that is now recognized as the first chatbot, a software application capable of engaging in conversation with humans. (The term itself emerged much later, in the 1990s, as an abbreviation for “chatterbot.”) Six decades after Eliza’s creation, the program’s inventor, Joseph Weizenbaum, is perhaps best remembered for spending the rest of his life warning the public of the dangers posed by such convincing technology.

When Weizenbaum, then a professor at MIT, wrote code that could mimic human language, his goal was to demonstrate technical capacity, not to illuminate human reaction to it. He thought the Rogerian style of psychotherapy, in which the client rather than the therapist takes the lead, would be the easiest form of conversation for a machine to emulate.

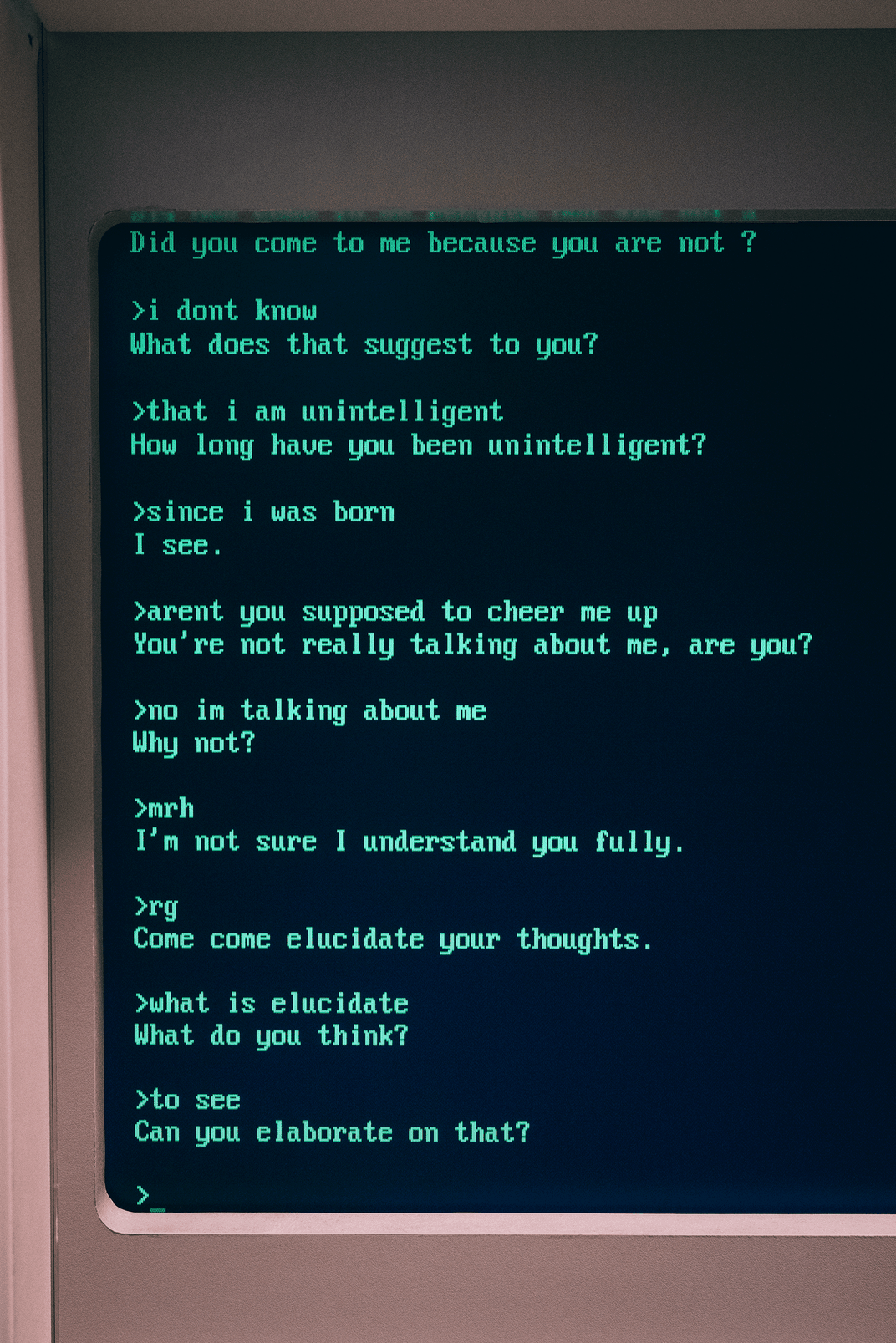

Eliza scanned for keywords inputted by users (such as “you” or “I”), then drew on an associated rule to generate a sentence or question in response: for example, “Who in particular are you thinking of?” If this formula didn’t work, Eliza was programmed to respond with a generic phrase like “please go on,” “I see” or “tell me more,” subtly prompting the user to divulge another keyword. The program didn’t need to be complex for this technique to work. “‘I am blah’ can be transformed to ‘How long have you been blah,’ independently of the meaning of ‘blah,’” Weizenbaum explained in a 1966 paper.

These scripts would “cause Eliza to respond roughly as would certain psychotherapists,” Weizenbaum wrote. That, in turn, enabled the speaker to “maintain his sense of being heard and understood.” When Weizenbaum’s secretary first tested the program, he later recalled, she asked him to leave the room so she could continue the conversation privately. This phenomenon of projecting human qualities onto a machine is now referred to as the “Eliza effect.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/33/87/338796e1-15a8-4997-b995-0cee0b1cbed0/julie_andrews_rex_harrison_my_fair_lady.jpeg) Julie Andrews as Eliza Doolittle in the 1956 stage musical My Fair Lady

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Julie Andrews as Eliza Doolittle in the 1956 stage musical My Fair Lady

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Weizenbaum named his chatbot after Eliza Doolittle, the working-class woman trained to pass as a member of high society in George Bernard Shaw’s 1913 play Pygmalion. In Greek mythology, Pygmalion was a king who fell in love with the statue he created. (Shaw’s play served as the basis for the 1964 Audrey Hepburn film My Fair Lady.)

“Some subjects have been very hard to convince that Eliza (with its present script) is not human,” Weizenbaum observed in his 1966 paper.

This realization alarmed Weizenbaum and crystallized a question that shaped the rest of his career and life. “What I had not realized is that extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people,” he wrote in 1976. “This insight led me to attach new importance to questions of the relationships between the individual and the computer, and hence to resolve to think about them.”

Such introspection was rare at a time when capability, not philosophy, was the driving force in the pursuit of new technologies.

The history of modern computingWeizenbaum’s career flourished at a promising juncture in the expansion of computing. He’d fled Nazi Germany with his family as a teenager in the 1930s, then served as a meteorologist in the United States Army during World War II. In the 1950s, he worked as a programmer for General Electric, where he helped create the Electronic Recording Machine, Accounting (ERMA), a system that transformed the banking industry by automating check processing.

Fun fact: A presidential connection Future U.S. President Ronald Reagan, then a spokesperson for General Electric, unveiled ERMA at a 1959 press conference.Scientists had envisioned technology mimicking human learning long before it was possible. When English mathematician Alan Turing posed the question “Can machines think?” in 1950, he posited that the answer should be measured by the “imitation game,” a level of sophistication at which a human cannot distinguish a machine from another human. This method is now known as the Turing test.

Turing was instrumental in creating the machine that allowed the Allies to crack the German Enigma code. He also helped develop an early precursor to modern computers, the general-purpose Pilot ACE.

Turing’s efforts harked back to earlier attempts to create an engine that could “arrange and combine its numerical quantities exactly as if they were letters or any other general symbols,” as an 1843 paper put it—in other words, a computer that could make the leap from numerical calculation to language.

The term “artificial intelligence,” meanwhile, emerged from a 1956 workshop on “thinking machines” at Dartmouth College. As the event’s organizers wrote in their proposal, researchers in the fields of computer science and cognitive psychology would come together to explore whether “every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it.”

Two of the scientists behind the gathering, Dartmouth’s John McCarthy and Harvard University’s Marvin Minsky, became pioneers of A.I. in the decades that followed—and they eventually found themselves on the opposite end of the spectrum from Weizenbaum.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1e/bb/1ebb0a33-5bdd-4f01-990c-3971c1569f8b/361777836_cf850b4d0f_o.jpg) L to R: MIT researchers Claude Shannon, John McCarthy, Edward Fredkin and Joseph Weizenbaum

Peter Haas via Flickr under CC BY-NC 2.0

L to R: MIT researchers Claude Shannon, John McCarthy, Edward Fredkin and Joseph Weizenbaum

Peter Haas via Flickr under CC BY-NC 2.0

Looking back at the workshop’s lineup, Dag Spicer, senior curator at the Computer History Museum, in Mountain View, California, says, “It’s like the computer science agenda for the next 50 years.” Despite limited computing capacity at the time, he adds, the organizers had a “kind of outlandish research agenda, but it turned out that that is pretty much what people did end up working on for the next five decades.”

In a 1961 paper, Minsky identified the enhancement of time-sharing technology, which enables multiple users in different locations to connect to a computer simultaneously, as a critical step in “our advance toward the development of ‘artificial intelligence.’” That goal was soon boosted by funding for the government’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), created after the launch of the Soviet satellite Sputnik in 1957. Military funding, not commercial interest, fueled research toward A.I. in the decades that followed.

McCarthy and Minsky founded the MIT A.I. Lab in 1959 and launched an initiative dedicated to expanding time-sharing possibilities a few years later. Weizenbaum, who joined MIT’s faculty as a visiting professor in 1963, was poised to capitalize on “these new languages and the interactive capabilities of a time-shared computer system,” wrote author Pamela McCorduck in Machines Who Think, a 1979 history of A.I. based on interviews with its founders.

The A.I. Lab’s work represented a leap forward in what computers could do when utilized as more than localized machines. In 1969, ARPA scientists built on this research to unveil Arpanet, a network that connected computers in different universities. The project was spurred by the military’s interest in “using computers for command and control,” according to the agency’s website. Arpanet served as a prelude to the expansion of the internet to everyday users in the 1990s and the social transformations that have followed.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b5/bc/b5bc9ac8-0694-4380-b1dc-39941baabfa7/arpanet_logical_map_march_1977.png) Arpanet logical map, circa 1977

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Weizenbaum’s break with other early A.I. pioneers

Arpanet logical map, circa 1977

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Weizenbaum’s break with other early A.I. pioneers

Weizenbaum’s efforts to create a computer program that could respond in English to English-language inputs relied on time-sharing technology developed at MIT. The challenge was twofold: First, Weizenbaum had to figure out how to code a program that could converse in natural language. Then, he had to determine what users might discuss with a computer that had limited knowledge of the outside world.

Mulling over “any conversations in which one of the parties doesn’t have to know anything,” Weizenbaum recalled in a 1984 interview with the St. Petersburg Times, he landed on the role of a psychiatrist. “Maybe if I thought about it ten minutes longer,” the computer scientist added, “I would have come up with a bartender.”

Though the idea of Eliza’s use in psychiatry eventually came to repulse Weizenbaum, it sparked enthusiasm among others in the A.I. field. Kenneth Colby, a Stanford University psychiatrist and erstwhile collaborator and friend of Weizenbaum, touted Eliza’s potential and adapted it into a program called Parry, which simulated paranoia from the perspective of a person with schizophrenia. Colby believed that A.I.-powered mental health tools would work well precisely because they were difficult to distinguish from a human therapist.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ac/a3/aca37d4d-555a-4feb-b269-acd1b26b04e1/102805275-05-01-acc_page_1.png) A circa 1966 printout of a conversation with Eliza

Computer History Museum / Gift of Emily White

A circa 1966 printout of a conversation with Eliza

Computer History Museum / Gift of Emily White

Even famed astronomer Carl Sagan was intrigued by the prospect. “I can imagine the development of a network of computer psychotherapeutic terminals,” he wrote in 1975, “something like arrays of large telephone booths, in which, for a few dollars a session, we would be able to talk with an attentive, tested and largely nondirective psychotherapist.”

Eliza “was instantly misunderstood as being basically the dawn of computerized psychiatry—which I detest,” Weizenbaum said in 1984. A few years later, he described the practice as “an obscene idea.”

In a “small community” that was “very parochial,” this rupture quickly became personal, Weizenbaum told McCorduck in an interview for her book. “The real break … arose over at the claim that Eliza was of therapeutic significance,” he said.

In 1976, Weizenbaum published a book titled Computer Power and Human Reason: From Judgment to Calculation. “The artificial intelligentsia argue, as we have seen, that there is no domain of human thought over which machines cannot range,” he wrote. In his view, however, “there are certain tasks which computers ought not be made to do, independent of whether computers can be made to do them.”

The book cemented Weizenbaum’s schism with other early pioneers of A.I. McCarthy deemed it “moralistic and incoherent,” accusing his former colleague of adopting a “more-human-than-thou” attitude. “Using computer programs as psychotherapists, as Colby proposed, would be moral if it would cure people,” McCarthy wrote.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3f/fd/3ffd8a36-2692-460f-be1c-d1a59f42d24c/the_vancouver_sun_1982_01_27_9_1.jpg) “The computer is a particularly seductive instrument because it offers immediate feedback,” Weizenbaum told a reporter in 1982. “But the thing that binds you to do it is that whatever the computer is doing is under your control.”

Vancouver Sun via Newspapers.com

“The computer is a particularly seductive instrument because it offers immediate feedback,” Weizenbaum told a reporter in 1982. “But the thing that binds you to do it is that whatever the computer is doing is under your control.”

Vancouver Sun via Newspapers.com

Fueling the fire were Weizenbaum’s political views, which put him at odds with MIT’s deep involvement in military research projects. He was a vocal critic of the Vietnam War, claiming that “computers operated by officers who had not the slightest idea of what went on inside their machines effectively chose which hamlets were to be bombed.” As the mathematician’s daughter Miriam Weizenbaum says, “He felt very alienated. He would refer to MIT as essentially a branch of the Defense Department.”

Weizenbaum also warned of A.I.’s potential use in surveillance technology: “Listening machines … will make monitoring of voice communication very much easier than it now is,” he wrote in Computer Power. McCarthy, for his part, decried Weizenbaum’s suggestion that the Pentagon would use speech-recognition research to eavesdrop on telephone calls as “biased, baseless, false,” and seemingly “motivated by political malice.” More recent debates, including those sparked by government surveillance under the Patriot Act, show that such applications have long since ceased to be theoretical.

“I have pronounced heresy, and I am a heretic,” Weizenbaum told the New York Times in 1977.

The future of artificial intelligenceMachines’ ability to mimic human thought improved with widespread adoption of the internet. In the 1990s, subsequent generations of chatbots, such as the online butler Ask Jeeves and Alice, the Artificial Linguistic Internet Computer Entity (winner of a prize based on the Turing test), made such capabilities available to the average computer user.

More recently, OpenAI’s ChatGPT, or Generative Pre-trained Transformer, debuted in 2022 and garnered 100 million downloads in just a few months. Today’s chatbots can devour reams of natural language and other data on the internet, which has made them exponentially more capable than their predecessors. Beyond language learning, they can create images and videos, as well as mimic human emotions.

Herbert Lin, a senior research scholar at Stanford who focuses on the impact of emerging technologies, says that comparing modern chatbots to Eliza is “like saying a 747 is similar to the Wright brothers’ plane.”

As technology has advanced, humans have grown susceptible to A.I.’s influence. Headlines about chatbots sparking paranoid or delusional thinking—including among people with no history of mental illness—or even violent behavior and self-harm are increasingly common. Parents of teenagers who died by suicide have spoken out about how chatbots encouraged their children’s suicidal ideation. Some users have fallen in love with their A.I. companions.

According to one 2025 study, 72 percent of teens have interacted with an A.I. companion at least once, and more than half turn to these tools regularly. Other studies illustrate the use of chatbots for emotional support or therapeutic purposes. Unlike licensed counselors, psychologists and psychiatrists, these influential virtual advisers remain largely unregulated, despite major companies’ assurances that safeguards are being strengthened.

“People can develop powerful attachments—and the bots don’t have the ethical training or oversight to handle that,” Jodi Halpern, a psychiatrist and bioethicist at the University of California, Berkeley, told NPR last year. “They’re products, not professionals.”

In Miriam’s view, her father “would recognize the tragedy of people attaching to literally zeros and ones, literally attaching to code.”

Throughout his life, Weizenbaum remained staunchly consistent in his views. He retired from MIT in 1988 and moved back to Germany in 1996. There, Weizenbaum found “an audience for his thinking,” Miriam says. Distanced from his U.S. peers, he was “recognized as a public intellectual,” Miriam adds. He remained in Germany until his death in 2008, at age 85.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/bb/89/bb894fc1-32ab-40a4-a706-6d64c980f93a/gettyimages-541768235.jpg) A 1997 photo of Joseph Weizenbaum

Joachim Schulz / ullstein bild via Getty Images

Weizenbaum’s legacy

A 1997 photo of Joseph Weizenbaum

Joachim Schulz / ullstein bild via Getty Images

Weizenbaum’s legacy

Speaking on a panel in 2008, Weizenbaum criticized the increasingly obscure nature of software programs used in everyday computing. “We’ve created a complex world which we have no control over anymore,” he said. “No one understands them anymore, no one can understand them, because we have lost the information about their creation, the history of their creation, and that is a great danger for mankind.”

Lin, who cites Weizenbaum as a key influence in his own career, also underscores the growing unpredictability of A.I. “The concern is that it will feed on itself and become better,” he says. In other words, the goal of machine learning (to process and synthesize vast amounts of information in an increasingly sophisticated manner) and the fear of its capacity are two sides of the same coin.

“Large programs are incomprehensible … and if things are incomprehensible, you don’t understand them anymore,” Lin explains. “How can you trust them? How can you rely on them? How do you know what they’re doing? That’s a big deal.”

Miriam stresses that her father’s “foundational humanism” undergirded his concerns about how new computing capabilities could be utilized—a perspective shaped by growing up in Europe during the interwar period. “It’s not just technology; it’s the abuse of power,” she says. Whether the issue was control over a human’s emotions or the execution of military operations, Weizenbaum believed that machines could never act as a substitute for human empathy or judgment.

“Since we do not now have any ways of making computers wise,” Weizenbaum cautioned in 1976, “we ought not now to give computers tasks that demand wisdom.” A user's conversation with Eliza

Marcin Wichary via Wikimedia Commons under CC BY 2.0

Get the latest History stories in your inbox.

A user's conversation with Eliza

Marcin Wichary via Wikimedia Commons under CC BY 2.0

Get the latest History stories in your inbox.

Comments (0)